Clean Growth Strategy marks break with past

Weighty roadmap indicate government now sees 'green' as gain, not pain

By Richard Black

Share

Last updated:

With the publication of its Clean Growth Strategy, Theresa May’s government confirmed that it has broken significantly with the low-carbon politics and rhetoric of the Cameron-Osborne era.

However many huskies Dave hugged, the dominant refrain of their government was Austerity George warning that Britain shouldn’t be ‘moving faster than other European nations’ (we weren’t at the time). It was defined by ultra-reductionist judging of future-oriented energy policy measures according to their impact on today’s bills, and by the abrupt cancellation of measures that everyone thought were in the can, notably Zero-Carbon Homes and the rollout of carbon capture and storage.

Dominated above all by the belief that ‘green’ hurts.

What a contrast with the philosophy put forward by Business Secretary Greg Clark and Climate Change Minister Claire Perry, then, as they launched the government’s flagship decarbonisation roadmap in London’s Olympic Park yesterday with the simple message that ‘green’ is good for the economy.

‘This government has put clean growth at the heart of its Industrial Strategy to increase productivity, boost people’s earning power and ensure Britain continues to lead the world in efforts to tackle climate change,’ Mr Clark told his audience.

Ms Perry continued: ‘By focusing on clean growth, we can cut the cost of energy, drive economic prosperity, create high value jobs and improve our quality of life.’

In other words: the ‘trilemma’ is over.

Forget that old troublesome triangle, where energy policy is a constant juggling act with competing priorities of security of supply, decarbonisation and cost, where pushing harder on any one element makes the other two suffer.

In the new model, ‘clean growth’ is the road to lower bills, lower carbon emissions and improved energy security. And there’s a fourth pillar – jobs, economic growth, prosperity. 'Green' as a driver, not an brake, for economic growth.

Route to a sea-change

What’s brought this change of tack?

Undoubtedly, having a serious Secretary of State in Greg Clark helps – not a politician over whom Tory activists slaver, but one you’d definitely trust to help with your maths homework. Under him, Claire Perry is clearly prepared to face down those few of her backbench colleagues who (weirdly, given that they include some of the most ardent Brexiteers) continue to talk down Britain’s ability to innovate its way through a low-carbon transition.

Politics with a capital P have helped – a chastening election result, and polling showing that young voters won’t put up with parties that flirt with climate scepticism.

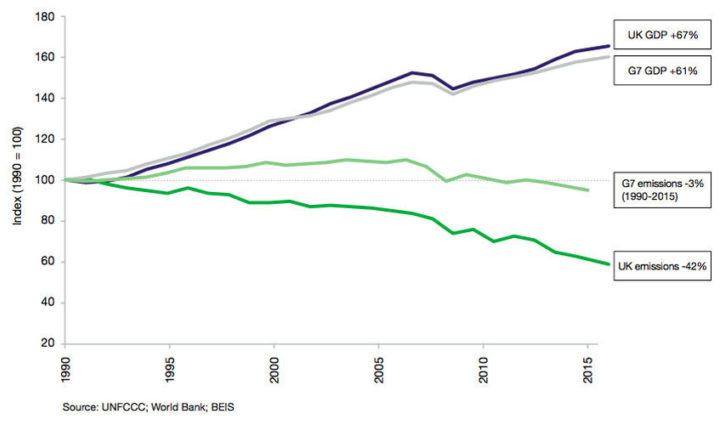

But most of all, it’s just evidence. The UK’s G7-leading performance – cutting emissions by 42% since 1990 while growing our economy by two-thirds – shows the doom-mongers are wrong.

The rapidly changing economics of renewables, energy storage and electric vehicles show the equations of the recent past don’t apply in the near future.

Though the components of the Clean Growth Strategy deserve (and have already had) close scrutiny, the philosophical sea-change is far too important to let pass without highlighting.

Delivering ambition?

So – onto the Strategy itself.

As I wrote earlier in the week, the Strategy has to tell us how the UK will, by the period 2028-2032, reduce its greenhouse gas emissions 57% below the 1990 baseline.

Despite the successes thus far, this 57% figure – the fifth carbon budget – is quite a big ask, because many of the easy things have been done already.

For example, well over two-thirds of UK houses already have loft insulation. Lower-carbon electricity generation technologies have already brought coal use below 10%. As easy things get done, making further cuts becomes harder.

To deliver carbon cuts on the scale required, the government had to look primarily at four things:

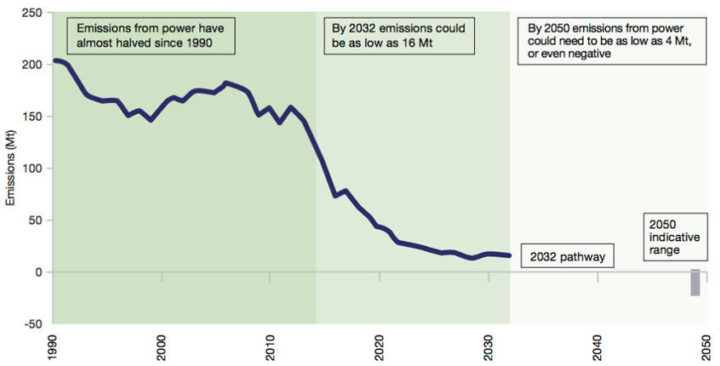

- keeping up the pace of change in the power sector so that by 2028-32 only about 10-20% of electricity comes from gas, the rest from low-carbon generation

- making big cuts in transport emissions, replacing petrol- and diesel-fuelled cars with electric and (maybe) hydrogen-powered models

- making some progress on the thorny problem of heating houses with low-carbon methods

- making energy use more efficient in homes, transport and industry.

Note that I haven't put firm numbers on any of those; that’s because the exact amount of progress needed in any one sector hinges on what happens in the others. However, analysis by the Committee on Climate Change, the government’s statutory advisor, suggests the prescription might include elements such as:

- one in six cars (and two-thirds of new sales) should be electric by 2030

- one in seven homes and one in two businesses should be heated by low-carbon means (such as heat pumps, biomass or solar thermal)

- 3.5 million homes should receive either solid or cavity-wall insulation between 2020 and 2030.

So: does the Clean Growth Strategy set out an adequate level of ambition, and tell us how it will be met?

Ambition – yes. Delivery – not really.

For example, the section on cutting energy waste from homes includes ‘wanting all fuel-poor homes to be upgraded to Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) Band C by 2030’, with the ‘aspiration’ that ‘as many [other] homes as possible‘ will join them on that level.

‘Want’? ‘Aspiration’? ‘As many as possible’? Hardly the language of firm, quantified policies. And there’s more of the same in other sectors.

There are many areas too where the exact path to be taken will be decided in conjunction with business, for example in cutting energy waste from industry – which will sound pragmatic to some observers, weak to others.

I won’t go through all the other components in detail as several others already have, including BusinessGreen and CarbonBrief.

One line that should be noted however is that almost two years after the government announced the aim of phasing out coal-fired generation by 2025, it’s now official. Just last month, when Theresa May spoke, it was still an ‘aim’– but here in the Clean Growth Strategy, it’s ‘we will’.

#YouHadOneJob...

Now – with all these vagueries, does the Clean Growth Strategy do the one job for which legally it exists – to tell us how the UK will meet the fifth carbon budget target?

In strict terms, it doesn’t. In fact, it forecasts that as things stand, with existing policies plus those in the Strategy that are sufficiently quantitative for projections to be made, we’ll fall short of that 57% cut.

Unsurprisingly, that’s had green activists claiming that the whole thing is a failure.

Still more so, given that the government highlighted a measure under the Climate Change Act allowing it to meet the fifth carbon budget through ‘flexibility mechanisms’ – in other words, ‘borrowing’ the credit for having outperfomed on the second and third carbon budgets, ‘borrowing’ more future credit from the sixth, and funding emission cuts overseas.

This earned ministers a rap on the knuckles from the Committee on Climate Change and the threat of legal action from activist lawyers ClientEarth – although since the Act allows ministers to use these mechanisms, it’s hard to see that ClientEarth has a case. (Full disclosure: I’m not a lawyer.)

Anyway – the point is that if this government and the next don't put the flesh of delivery on the bones of ambition, the green groups will be right – the strategy will be a failure.

However… to believe that nothing more will happen over the next 15 years is really to suspend rational judgement.

You’d have to believe that none of the processes the Strategy sets in train will be taken seriously and result in any additional carbon savings.

You’d have to forget the lesson learned from the last decade wherein time and again, components of the clean energy system have out-performed forecasts. And globally, progress has been accelerated on all fronts by the Paris Agreement. So why would you presume these real-world factors will suddenly start passing the UK by?

You’d have to believe that the fundamental politics will suddenly change, which is vanishingly unlikely. The younger politician who understands public disaffection with Britain’s tiny but rich climate-sceptic elite is not suddenly going to start giving constituents sacks of coal for Christmas as a route to re-election.

The Clean Growth Strategy is not a fully fleshed-out plan for decarbonisation. It contains some elements of a plan, but other elements will need to be slotted into place in the coming years. Meanwhile disruptive technological advances – some of which ministers aim to encourage through markets and regulation – will create opportunities for radical change that may be unforeseeable now. At some point the government will have big strategic choices to make, notably on low-carbon home heating, which may not be easy.

But to return where we came in: this is a government that sees the whole notion of clean growth very differently from its predecessor. A philosophy alone doesn't cut carbon emissions. But a philosophy that sees 'clean' as good for the economy and for people is far more likely to do so than one that sees hair shirts everywhere.

Share