Flood risk and the UK

How will flood risk to the UK change in future - and are we prepared?

By Richard Black

@_richardblackShare

Last updated:

Record-breaking weather

In the UK, the top 10 warmest years have all occurred since 2002. The longest-running instrumental record of temperature in the world, run by the Met Office’s Central England Temperature data sets, reveals that 2009-2018 was around 1°C warmer than 1850-1900. Several other records have been broken too:

- The winter of 2013/14 was the wettest winter since records began in 1910. Of the top ten wettest winters, four have occurred since 2007 and seven since 1990.

- December 2015 was not only the wettest December on record, but also the wettest calendar month overall since records began in 1910.

- February 2020 was the wettest February on record for England, Wales and Northern Ireland, and the second wettest for Scotland.

- The rainfall from Storm Desmond in 2015 also broke records; Honister, Cumbria, received 341mm (13.4 in) within 24 hours, breaking the November 2009 record of 316.4mm.

And, heavy rains are becoming even more common. According to the Met Office, the most recent decade (2009-2018) has been on average 1% wetter than 1981-2010 and 5% wetter than 1961-1990 for the UK overall – and the amount of rain from extremely wet days has increased by 17% when looking at the same periods.

Flooding projections

Climate change has made the devastating events, such as Storm Desmond in 2015, 59% more likely, according to research conducted by Oxford University and the Royal Meteorological Institute.

Meanwhile the Met Office forecasts that intense rainfall associated with severe flash flooding could become almost five times more likely by the end of this century.

The UK’s first Climate Change Risk Assessment (CCRA), in 2012, found that increased river flow resulting from extreme rainfall, plus sea level rise, will increase flood risk.

According to the most recent CCRA report, an estimated 1.8 million people are living in areas of the UK that are at significant risk of coastal, surface or river flooding. The population of people living in such areas is projected to rise to 2.6 million by the 2050s under a 2°C scenario and 3.3 million under a 4°C scenario, assuming a continuation of current levels of adaptation and a low population growth.

Along the English Channel coast, the sea level has already risen by about 12cm in the last 100 years. With the warming we are already committed to over the next few decades, we can expect a further 11-16cm of sea level rise by 2030. This equates to 23-27cm of total sea level rise since 1900.

Flooding already poses a risk to vital infrastructure such as roads, fresh water supplies, sewage treatment plants, hospitals, schools and energy supplies, and the risk is projected to rise. By the 2080s, up to 1,800 schools could be exposed to ‘significant likelihood’ of flooding (a greater than 1 in 75 annual chance).

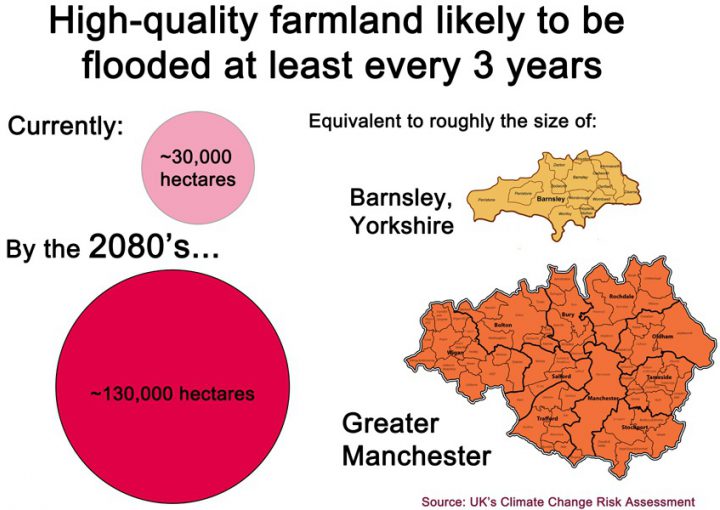

During the decade of the 2020s, 35,000 hectares of high-quality horticultural and arable land are likely to be flooded at least once every three years. By the 2080’s this will reach 130,000 hectares of high quality land – an area larger than Greater Manchester.

Additional flood protection measures could reduce the flood risk to homes, infrastructure and farms – but deterioration of flood defences, or more building on flood plains, increases the risk further.

Costs

Flood damage currently costs the UK around £1.3 billion each year; the total economic damages for England from the winter 2015 to 2016 floods were estimated to around £1.6 billion, with 32% of total damages occurring to the business sector.

Low income households are amongst the most at risk to flooding and the detrimental financial consequences; they are eight times more likely to live in tidal floodplains than affluent households and 61% of low-income renters do not have home contents insurance, leaving them more susceptible to experiencing a financial shock.

Flooding also has an impact on human health, including mental health. Research found that people who experience extreme weather events such as storms or flooding are 50% more likely to suffer from mental health problems, including depression and anxiety, while a quarter of people who have been flooded still live with these issues at least two years after the event.

The economic loss and damage from flooding in the UK is projected to increase.

There is a 10% chance of a catastrophic flood happening in England within the next two decades causing in excess of £10 billion in damage. Such a flood would cause 10 times more flood damage than the combined impact of the tidal surge and storms in winter 2013/14, and 3 to 4 times more damage than in 2007.

Is the UK prepared?

According to the Association of British Insurers (ABI) over 82,000 people claimed for flood or wind damage as a result of storms Dennis and Ciara in February 2020 and the total cost of repairing homes and businesses is expected to top £360 million.

The Committee on Climate Change’s (CCC) 2012 Progress Reports called for a national, long-term, outcomes-based adaptation strategy to address the increasing flood risk to be developed. The 2019 report highlighted that plans and actions to address increasing risk were lacking in development policy, property-level flood resilience and sustainable urban drainage.

The CCC warned in a letter to government in 2020 against shaping future policy on the experiences of the past, given the threat of further extreme weather and sea level rises.

It said: ‘We have a world class track record of delivering high quality flood and coastal defences. However, we cannot afford to continue to build our way out of future climate risks in many places.

Instead, we need to plan for the challenges we will face in the future. We need to support communities to plan better and – in some cases – adapt to future flooding and coastal change. This requires action now so that the UK’s population and economy are ready for what the future may bring.’

National standards ‘will enable all types of places to achieve an appropriate level of resilience that reduces the likelihood and/or consequences of flooding and coastal change for people, infrastructure, the economy and the environment’.

Their introduction and implementation would help make ‘the best land use and development choices… and support international leadership in the run up to the COP26 climate talks’.

In July 2020, the Government and Environment Agency announced a new £5.2 billion flood prevention and coastal management strategy to be brought in over the next 10 years, including protection of 336,000 properties in England by 2027. The plan was generally welcomed positively, but the National Infrastructure Commission warned that more may need to be done, expressing their view that “we are hopeful that today's plan marks the beginning of the end of reactive cycles of funding, and a fresh focus on levelling up flood resilience for communities across the UK."

The NAO argues that investing in flood defences is highly cost-effective, concluding that each £1 not invested means communities will suffer up to £8 in unnecessary flood damage.

The Thames Barrier & risks to London

In 2014, the Thames Barrier closed 48 times before the middle of March – a record for a single year. More than a quarter of the total closures in the Barrier’s 32-year history occurred in the 2013/14 winter.

Some 1.3 million people live in the Thames tidal floodplain and are therefore vulnerable to flooding if current defences were to fail or were overtaken by climate-induced sea level rise; £275bn worth of property is also at risk.

The Environment Agency’s TE2100 Plan highlights that without effective mitigation of global greenhouse gas emissions, the Thames estuary may have to deal with sea level rise that exceeds the Barrier’s capacity.

Share