Net zero transport - battery electric vehicles

What are the benefits and challenges of rolling out battery electric vehicles?

By Dr Simon Cran-McGreehin

@SimonCMcGShare

Last updated:

Surface transport (road and rail) accounts for 37% of global CO2 emissions, and 22% of UK emissions. Evidence from the IEA shows that “owing to efficiency improvements, electrification and greater use of biofuels”, emissions increases are slowing with a roughly 0.5% increase in 2019 being lower than the average of 1.9% increase in the years since 2000.

Battery electric vehicles (BEVs) are powered entirely by electric batteries, with no petrol or diesel engine. BEVs are being pursued by most governments and automotive companies as the main low-carbon option for light road transport (cars and vans).

Climate and other benefits of BEVs

In the UK, the Climate Change Committee (CCC – Government advisors on how to meet climate goals), has estimated that around half of the emissions reductions needed from surface transport to meet net zero will come from zero-emission cars - almost entirely BEVs.

The life-cycle emissions of a BEV are over two-thirds lower than a fossil fuel car, with manufacturing emissions being cancelled out by lower in-use emissions within a year. And the value for BEVs are expected to fall further from 15 to around 8 tonnes of CO2 by 2030 as manufacture improves and the cars run on lower-carbon electricity.

BEVs have lower fuel costs than alternatives, at around half the price per km of petrol or diesel.[1] These lower energy costs are partly due to BEV’s much higher efficiency. Petrol engines are around 20% efficient, and diesel up to 40%, with further inefficiencies in the production and transportation of those fuels. Electric motors are around 90% efficient, and the production of the electricity they use is becoming increasingly efficient with the greater use of renewables.

Manufacturing, jobs and supply chains

Countries around the world are racing to build ‘gigafactories’ to manufacture lithium-ion batteries for BEVs in order to retain (or attract) large motor manufacturing companies. China which leads the world in this sector has 149 gigafactories planned by 2030. EU States have 19 planned, and the USA 11. Overseas examples of planned gigafactories include construction of the 60GWh Northvolt plant in Sweden (which has a $14billion contract with Volkswagen), and Germany alone has seven plants under construction.

The UK has one existing gigafactory to manufacture lithium-ion batteries for BEVs, the Envision AESC plant in Sunderland, which has recently announced it is expanding to create 6,200 jobs. Britishvolt is constructing another in Blyth, expected to begin production in 2023. This new plant is likely to provide for 300,000 BEVs per year and create 3,000 jobs (at the plant and in supply chains), presenting an opportunity for jobs in industrial areas key to the ‘levelling up’ agenda.

The Faraday Institution predicts that the UK will need at least one new gigafactory from 2022, another from 2025, and eight by 2040. The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) also estimates that, by 2030, the UK will need enough gigafactories to provide for 1 million electric vehicles per year. Co-locating vehicle and battery factories can have multiple practical benefits, including: easier collaboration with researchers and supply chains; limiting transport costs; and satisfying the ‘Rules of Origin’ in the EU-UK trade deal stating that the battery (and 55% of the vehicle overall) must be manufactured in the UK or EU.

Raw Materials

BEV and battery manufacturing relies on securing supplies of key materials (particularly critical raw materials such as lithium and cobalt), which are found almost entirely outside of Europe. China has spent decades building up control of global production of key minerals to support its manufacturing industries and the UK has no critical raw materials strategy, although this has been recommended in a 2020 Defra-commissioned report.

There are efforts to move away from lithium-ion batteries, partly to reduce exposure to these international issues, and partly to avoid negative environmental impacts of lithium-ion battery supply chains and disposal. It has been suggested that the UK could seek to obtain strategic and economic advantages: developing industrial-scale recycling of batteries to provide a source of materials for its gigafactories; and researching solid-state batteries for BEVs to leapfrog manufacturing competitors.

Sales new BEV cars

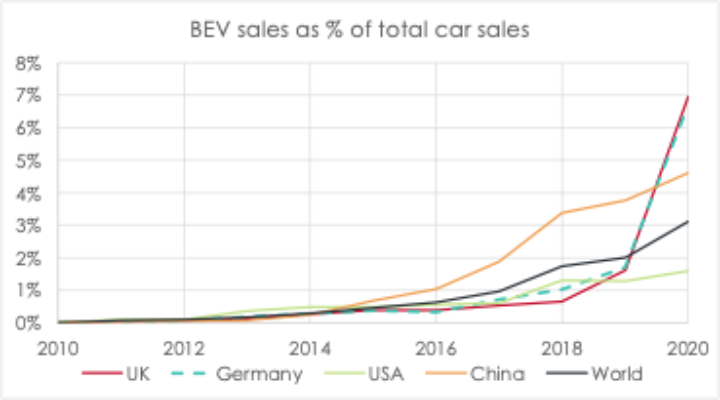

The popularity of BEVs continues to grow, and sales are following suit. UK BEV sales up to the end of September 2021 reached 9.5% of all car sales (125,000 cars), with sales of 32,000 in September 2021 alone approaching those for the whole of 2019 (38,000). This is expected to continue; the OBR estimates that BEVs will make up 16% of new car sales by 2025/26, and the CCC anticipates that EVs will make up 90-100% of new car sales by 2030 (including some plug-in hybrid electric cars before new sales are phased out by 2035).

Similar trends are seen across Europe - data for 2020 shows Germany had a rapid rise in uptake, reaching almost 7% of all car sales and overtaking sales in China (4.6%). However, sales in some countries have surpassed this significantly already, such as Norway where sales reached 7% in 2014 and 54% in 2020.

Sales growth has been due to BEV performance compared to conventional cars, coupled with public concern about climate change and the health impacts of air pollution from petrol and diesel. The growth in the UK in 2021 has also been partly attributed to public concern over fossil fuels during UK’s fuel distribution crisis. Policy has also influenced buying decisions, such as the announcement of a ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars and vans from 2030.

Stock – vehicles on the road

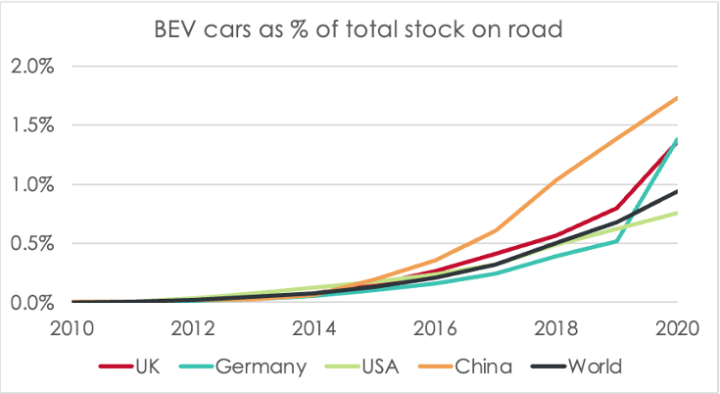

The UK’s Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) estimates that BEVs will make up 4% of cars on the road in the UK by 2025/26 – four times higher than today, in the space of just 4 years. As of September 2021, around 1% of the UK vehicle fleet was a BEV[2] (320,000 BEVs).

The latest global data from the IEA for the end of 2020, shows that in China BEVs accounted for 1.7% of the car stock, followed by the UK (207,000) and Germany on 1.4%. Norway was at 17%. The ratio of BEVs per 100,000 people shows similar levels: Germany and the UK had 400 and 300 BEVs per 100,000 people at the end of 2020, respectively, with Norway at 6,300.

Charging infrastructure

Charging infrastructure will form a key part of BEV roll out, including home chargers, public chargers, and the power grids that supply them. The UK had around 26,000 public chargers as of mid-October 2021[3] with the CCC estimating around 280,000 public chargers will be required by 2030. This would equate to 45 BEVs ‘sharing’ each public charger across the UK – this is one of the measures used by analysts to assess the sufficiency of the charging network, albeit that some users would also have access to private chargers.

The UK Government has confirmed requirements for charging points at new homes and offices as soon as 2022 and committed £1.3 billion to support

deployment of public chargers but there are concerns about access to charging at flats and existing homes. Public chargers are being installed by local authorities and private companies, including rapid chargers for example at service stations. Ofgem has announced funding to connect 1,800 new ultra-rapid charge points (tripling the current network) and a further 1,750 charge points in towns and cities.

[1] Typical fuel consumption for a new conventional car is 5.7 litres per 100 km (petrol) and 5.1 litres per 100 km (diesel); at fuel costs of around £1.30 per litre, these equate to about £7.40 and £6.60 per 100km, respectively. A BEV would typically require approximately £3 of charge to cover the same distance, which is about half the price of petrol or diesel. See RAC Foundation, ‘Environment’ (2021), and also House of Commons Library, ‘Electric vehicles and infrastructure’, Library Note, CBP-7480, 23 June 2021, p 14

[2] The UK had 265,584 as of end 2020 (see DfT table VEH0133b), and added 125,721 to the end of September 2021.

[3] Terminology about chargers can be a bit slack. Usually, ‘charger’ means a device that can have one or more ‘connections’ i.e. some devices can charge more than one car at a time. As of 21 October 2021, the UK had 26,482 chargers with 45,255 connections at 16,639 different locations.