China and UK nuclear power

What's happening with nuclear generation in the UK, and how is China involved?

By Jess Ralston

@jessralston2Share

Last updated:

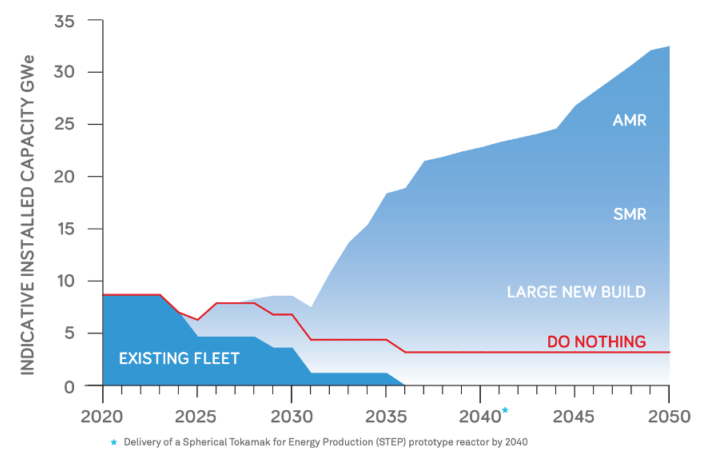

Britain’s eight nuclear power stations generate a fifth of the nation’s electricity supply. However, all but one of the plants currently operating are due to shut down by 2030 (figure 1). At the same time, progress on building a new fleet of reactors has stalled.

Rapid cost reductions mean that renewable generators are expected to form the backbone of the UK’s electricity system in the future. However, the Climate Change Committee still estimate that nuclear power plants that are under construction now (Hinkley), and those planned for the future (Sizewell and Bradwell), could meet up to 11% of generation in 2050.

So where is all this nuclear generation going to come from?

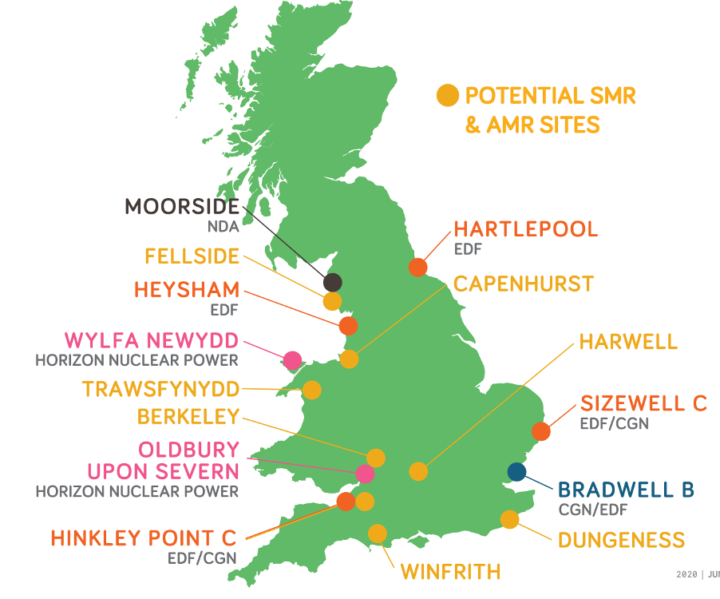

In 2008, the then-Labour Government announced plans for a new generation of nuclear power in the UK to help meet the 30-35 GW of electricity demand that it thought would be required by 2030. After this, eight sites in England and Wales were identified as suitable for development. Many of them already had some nuclear reactors present.

Plans for all but three of these sites have now been put on hold, as companies proposing to build reactors have been unable or unwilling to make final investment decisions. Of those that remain, construction is underway at Hinkley Point and the industry is hopeful that plants can be built at Sizewell (copying the Hinkley design) and Bradwell.

The future of funding for new nuclear power in the UK is uncertain. The Government has proposed a funding model, the Regulated Asset Base (RAB) which de-risks the investment for investors but puts the risk of overruns and increased spend in construction onto consumers. There are also other models, such as the Government taking a direct equity stake in projects. It is very unlikely that nuclear projects will be delivered without intervention from the Government.

What’s China’s involvement with new nuclear power plants?

China has been interested in exporting its nuclear fleet to many countries including France and across the developing world. It also generated 4.2% of its own electricity from nuclear in 2018, from 47 plants around the country.

And in the UK, in 2014 under the coalition Government the UK-China Energy Dialogue was agreed between the two countries with one major focus being the use of clean energy including nuclear.

Following this, the Government announced their approach to nuclear projects would be ‘developer-led’. This meant that as long as relevant permissions were granted on the proposed site, and finance secured for the scheme, there would be no barriers to the development of nuclear energy in the UK.

It appears that China deemed this an opportunity to export its nuclear expertise and have since made it clear that it wishes to be a global leader in nuclear power – using UK as a springboard to showcase its successes to other countries. Away from the UK it could then replicate technology and business models to generate income, also promoting China as an important power across the world and ensuring that other countries want to invest and be on good terms with the nation to win political favour.

The state-owned China General Nuclear Power Group (CGN) began showing interest in UK nuclear sites, starting with bidding on the nuclear plant Wylfa in Angelsey as part of a consortium in 2012, which has now been scrapped.

Now, CGN works with EDF on several nuclear projects in the UK, including Hinkley Point C where CGN own a 33.5% stake. The organisations are also working together on proposals for a new plant at Bradwell in Essex, in which CGN will hold the majority (66.5%) stake and EDF play a supporting role.

What are the concerns with Chinese involvement in the UK?

In 2016, then-Prime Minister Theresa May temporarily halted crucial documentation that issued a subsidy towards the Hinkley project over concerns with Chinese involvement. Again in July 2020, the Director of the Centre for Security and Intelligence Studies at the University of Buckingham said that having China involved in nuclear projects could be a ‘ticking time bomb’.

But since worries began surrounding Chinese state-owned technology company Huawei’s involvement in the UK’s 5G network, there have been larger concerns raised over CGN’s involvement in nuclear energy plants, particularly from other countries including the USA.

In fact, a previous US Secretary of State accused Beijing of ‘coercive bullying tactics’ and affirmed that the US ‘stands ready to assist our friends in the UK with any needs they have’. He suggested that the Chinese Communist Party was using Huawei to extend its surveillance practices in other countries and some fear similar issues could arise from Chinese involvement with nuclear power as well as 5G infrastructure. Now there is a new administration under President Biden, the relationship with China may differ, but this remains to be seen.

Essentially concerns in nuclear power boil down to similar issues as 5G. Some people are hesitant to accept Chinese involvement in infrastructure projects over fears of cyber-security breaches and spying. Ex-Chancellor George Osborne was even rumoured to say about spying ‘they are going to do it anyway so we might as well get the investment’.

However, it is likely that a large role in this is politics and long-standing tension between Britain and Beijing over issues such as Hong Kong that may also be adding fuel to the fire.

Others have urged caution with Labour’s Peter Mandelson expressing his view that the UK should not make an enemy of China, as it has the second biggest economy in the world (behind the US), and he highlighted he thinks that Western countries need to have good relations with China to do business there.

Although clearly a thorny issue, for now, it seems likely that both nuclear (and Chinese investment in such projects) will continue to 2050 in order for the UK to reach net zero.

There may be alternatives; some observers are advocating small modular reactors that are being developed in the UK for example, but the technology is still nascent, or progress in renewables and battery storage undermines the case for ‘firm’ technologies (those that can provide a known amount of power consistently) like nuclear. Either way, the National Infrastructure Commission recommend that just one more large nuclear power plant is built after Hinkley so the decline in nuclear power seems inevitable.