Fracking in the UK

Economics, resources, public opinion - what are the prospects for shale oil and gas?

By Richard Black

@_richardblackShare

Last updated:

Fracking, short for ‘hydraulic fracturing’ is:

- the process of extracting oil and natural gas from shale rock underground

- controversial because the process can cause water pollution, while continued extraction and burning of fossil fuels contribute towards climate change.

Fracking: US and Europe

A fracking boom has seen US oil production surge to a 50-year high, turning the US into a net exporter of oil and overtaking Saudi Arabia in terms of barrels produced.

Shale gas has rebalanced global markets, reduced energy prices and had geopolitical consequences. Carbon emissions have fallen – especially in the US – as cheap natural gas replaces more polluting coal in power generation.

Many European nations, though, have banned or restricted fracking activity. The UK Government signalled the end of the road for fracking in 2019 following a near-decade of support for the industry.

What is hydraulic fracturing?

Fracking began in the late 1940s in the US. Beginning in the 1970s, a series of technical developments made it increasingly suitable for use in formations of shale rock that contain oil or gas.

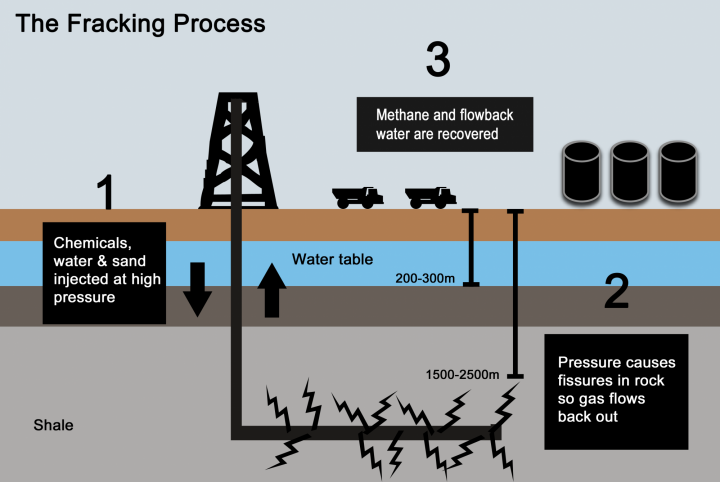

Operators usually drill a vertical well into the shale layer. Then the drill is used horizontally to penetrate sideways. A mixture of water, chemicals and sand is pumped in under high pressure, creating fractures in the shale. Tiny particles of sand prop open the fractures, allowing oil and gas to escape, eventually to the surface.

Chemically, the gas produced from fracked shale wells is identical to that from orthodox wells – methane (CH4), also known as natural gas.

Following the boom in US shale oil, the number of natural gas wells almost doubled from 2000-10, allowing 89% of gas consumption to be produced domestically. The recent drop in oil and gas prices has slowed investment and extraction in the US.

The US has largely replaced Saudi Arabia as the swing producer of crude oil, as American rig operations respond to fluctuations in the oil price while Saudi extraction remains constant.

China and fracking

China has found replicating the US experience harder than expected, despite having the largest recoverable shale deposits in the world. China’s latest five-year plan outlines aims to produce 15% of its natural gas consumption from shale gas by 2020, outlining it as a policy priority. Within Europe, governments in Bulgaria, France and Germany have banned fracking, while a temporary moratorium has been in place in the Netherlands since 2013.

Fracking in the UK

The UK contains shale formations bearing oil in the south and gas in the north. The Bowland Shale in the north of England is thought to contain about 1,300 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of gas. By comparison, the UK consumes about 3 Tcf per year.

However, only a small proportion of gas in the Bowland can be extracted – perhaps only about 4%. Compared with North America, the shale geology of the UK is considerably more complex, faults are numerous, and drilling costs are substantially higher [pdf link].

Despite this, proponents of UK fracking said that it could duplicate the US experience and lead to a cheap energy boom. The Conservative Government led by David Cameron called for the UK to go ‘all out’ for shale, removing the final say over whether projects could go ahead from local councils.

Fracking not economically viable

The Institute of Directors calculates that the UK shale industry could support 74,000 jobs, but this is not independently corroborated.

Exploratory drilling in Lancashire, by Cuadrilla, was halted in 2011 after fracking caused two earth tremors. Surveys in Balcombe, Sussex were also carried out by Cuadrilla, opposed by local and environmental protesters, although plans to frack were dropped.

A turning point came in April 2016 when North Yorkshire council approved Third Energy’s proposal to frack an existing well in Kirby Misperton, despite objections from the majority of the local population.

However, long-running questions over the viability of a British fracking industry, as well as high levels of public opposition saw a moratorium placed on the technique during the 2019 election campaign, effectively killing the industry.

A string of earthquakes at fracking sites appear to have been the final straws for ministers.

A report by the UK Energy Research Centre (UKERC) concluded that shale gas would not reduce energy prices or reduce the UK’s reliance on gas imports. It also pointed to the highly interconnected nature of European gas markets as a reason why fracking would not deliver cheaper fuel prices.

Is fracking an environmental threat?

Fracking has been linked to a number of issues including:

- groundwater contamination

- air pollution

- surface water pollution

- health problems.

Research supports some of these claims. For example, researchers found evidence of dissolved methane in drinking water wells in New York and Pennsylvania associated with shale-gas extraction. Methane is flammable, so can cause explosions. There have been reports of methane bubbling out of kitchen taps.

An earthquake of 3.0 magnitude occurred in March 2014 in Ohio within 1km of active fracking operations. Tremors of similar strength were also seen in the UK, with an event at Cuadrilla’s Blackpool site registering at 2.9 in August 2019.

In response to this tremor, the Government commissioned the UK’s Oil and Gas Authority to assess the viability of the industry. It said that future seismic activity could not be ruled out.

Surface spills and improper disposal are highly feasible in some areas, especially given the vast amount of waste fluid to be disposed of. Health impacts can also affect animals and pets. Hazardous air pollution resulting from volatile compounds is another concern.

There is the potential for drinking water to be contaminated with toxic chemicals. Hundreds of chemicals are involved in fracking and some can cause cancer, with pregnant women and children particularly sensitive to health risks. Groundwater near drilling regions in Colorado had an increased concentration of hormone-disrupting chemicals, while higher levels of birth defects have been observed near drilling areas.

However, in the US, a comprehensive study by the Environmental Protection Agency found that while there were isolated cases of contamination, fracking for shale oil and gas has not led to widespread pollution of drinking water.

Is shale gas good or bad for the climate?

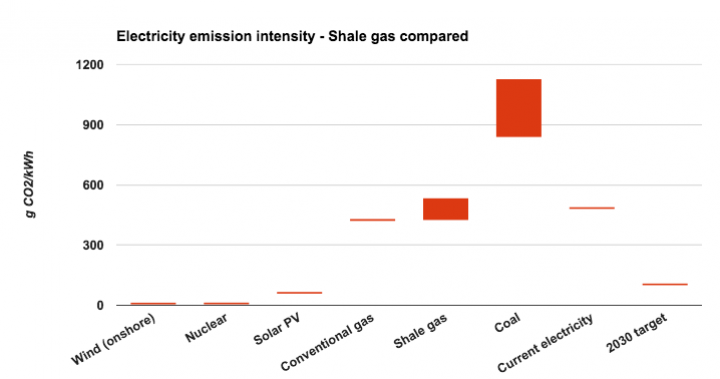

Shale gas can affect climate change in two ways.

- Methane can leak from wells and pipes into the air, where it acts as a greenhouse gas.

- Shale gas burning can displace either lower-carbon technologies such as renewables, or higher-carbon activities such as coal burning, so increasing or decreasing carbon dioxide emissions.

Methane release occurs if pipes leak or if wells are not properly sealed with concrete. By weight, methane is 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide as a greenhouse gas.

On the positive side, burning natural gas releases about half as much carbon dioxide as coal. As long as leakages are well-regulated, UK shale gas could have lower emissions than importing liquefied natural gas (LNG) from Qatar, because less energy is used in processing and transport. In the US, switching to gas for electricity contributed to domestic emission reductions, but globally, it is estimated more than half these reductions were cancelled out by increased coal exports and coal-burning abroad.

In some economies, gas can replace coal as a ‘bridge’ to a low-carbon electricity system. However, in the UK this is unlikely.

Reaching the UK’s legally binding ‘net zero’ 2050 emissions target involves ‘virtually decarbonising’ electricity generation by 2030. It also sees limited role for natural gas as a source of heat, instead being replaced by electricity and other carbon-free alternatives.

In 2015 the Environmental Audit Committee concluded: ‘extensive production of unconventional gas through fracking is inconsistent with the UK's obligations under the Climate Change Act’. [NB this refers to the previous 80% emissions reduction target]