Climate impacts on UK food imports

Spotlight on: the Mediterranean

Last updated:

Climate change is driving more extreme weather, including hotter, longer and more frequent heatwaves. Extreme heat, along with resulting drought, wildfires and subsequent flooding when rain comes, destroys crops and harms agriculture.

With half the UK’s food imported from overseas, worsening climate impacts threaten our food security by impacting British staples. This could lead to food shortages and price rises, on top of those already caused by the gas crisis.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has declared unequivocally that humans have heated the planet by an average of 1.1°C since pre-industrial times; scientists working to attribute the effect of climate change on extreme weather phenomena work on the basis that it is now closer to 1.2°C. Europe is warming at twice the rate of the global average over the last three decades.

And the nations in southern Europe and northern Africa, around the Mediterranean, have experienced some of the worst heat extremes ever in the last few years.

Europe saw its hottest summer in 2022; extreme heat that was estimated to have caused more than 61,000 additional deaths, nearly 3,500 of which were in the UK. It also led to widespread drought which harmed food harvests. 2023 has seen the world’s hottest June on record; a succession of the hottest days ever recorded; the hottest sea surface temperatures and, in July, the hottest month ever experienced by modern humans.

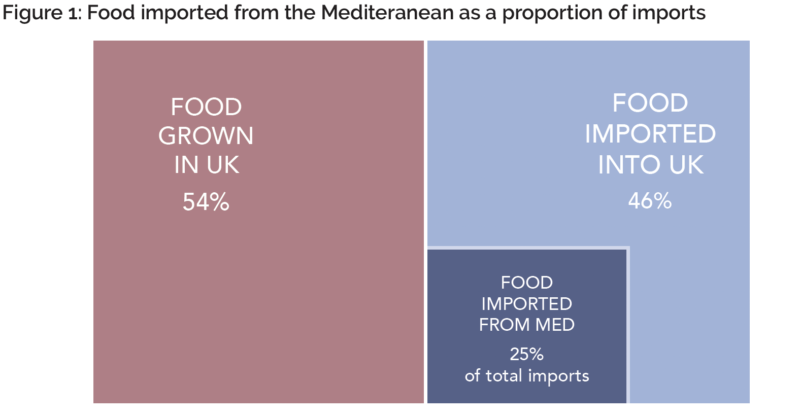

In 2022, the UK imported around half its food from overseas: 37 billion kilograms, worth £58 billion. Half of that was food that we do not grow here. Just over a quarter of UK food imports – 9.8 billion kilograms, worth just over £16 billion – came from the Mediterranean region, most of which was staple fresh produce like fruit and vegetables, core to a healthy diet.

Spain alone, which is experiencing some of the worst climate impacts in the region, accounted for 7% of our food imports - worth £4 billion.

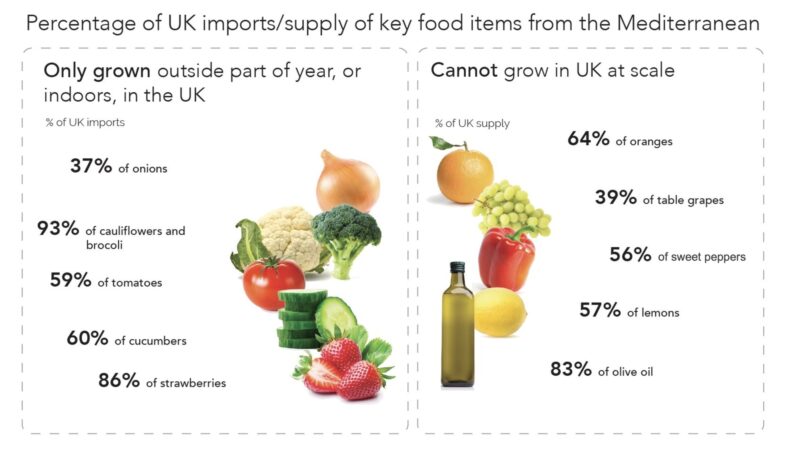

Some of the commodities we import from the Mediterranean are foods that we can grow outside in the UK for at least parts of the year, or that we can grow indoors, using more expensive and energy-intensive processes to protect them and heat the growing space.

But many are foods that we simply cannot grow in the UK at-scale. In the former category, this includes nearly all of the cauliflowers, broccoli and strawberries, and nearly two-thirds of the cucumbers and tomatoes which we import, as well as nearly a fifth of our overall supply of onions. In the latter category, more than half of our lemons and sweet peppers come from the Mediterranean, along with two thirds of all our oranges and 40% of our table grapes. We rely on the region for over 80% of our olive oil – a commodity that has surged in price so much recently that it comes near the top of the list of foodstuffs behind the UK’s sharp food price rises, and therefore contributing to overall inflation.

Reduced yields mean less food in our shops and markets, and higher prices for the commodities affected.

UK households have already seen food price rises averaging £400 last year, as a result of climate impacts and fossil fuel price volatility.

The growing threat from climate impacts this year shows every sign of adding to this, thus exacerbating the cost-of-living crisis, worsening the impact on poorer families, and threatening nutrition levels.

It is sometimes suggested we replace commodities at risk by switching suppliers, repurposing land to grow more here, or even growing new foods as our own climate warms. However, climate impacts do not respect borders.

Even if the world succeeds in keeping temperature rises to 1.5°C, food producers in the UK, and worldwide, already face the need to adapt to these new climate extremes of higher average temperatures than humans have been used to for most of our existence on Earth. Sharing best practice, as well as both government and private investment in that adaptation, can be an important means of mitigating the scale of the threat to food supplies.

Climate impacts worsen as temperatures rise. We can, according to the IPCC, only adapt to those impacts up to a certain point; and temperature rises up to and beyond 2°C lead to irreversible losses of ecosystems. The only means currently available of stopping climate change and limiting temperature rises, is to phase out reliance on fossil fuels and ramp up deployment of renewable power and other clean technology to reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions globally by mid-century.

It is this that the nations of the world have committed to under the Paris Agreement, with wealthier developed countries getting to net-zero earlier, while supporting poorer and developing nations with climate finance to adapt to climate impacts, cut emissions themselves, and to recover from climate disaster.

Climate change is a global threat and a threat multiplier. Impacts in a globalised world are felt on the other side of the planet, as crucial supply chains are affected. Solutions are similarly global and shared, with the IPCC’s sixth assessment report clear that we not only have the solutions we need to halve emissions this decade, and get on track for net zero, but also that to do so is cheaper than the alternative of bearing the ever-growing costs of climate impacts.

For the UK, and other major industrialised economies, this means living up to our international commitments and the climate leadership we have shown in the past. But it is also increasingly a matter of protecting our national security and that of our food supplies.