Bitter pill for the UK’s energy sweetheart

Dark clouds hang over solar future, despite record progress and popular support

By Richard Black

Share

Last updated:

By Richard Black, ECIU Director

It’s been a bittersweet and slightly surreal few days for Britain’s favourite form of energy, solar power.

‘Favourite?’

Well – yes. No doubt about it. If we’re prepared, as citizens, journalists and politicians, to base election predictions on differences of a few percentage points between the parties, it would surely be illogical to ignore the findings of survey after survey showing at least 80% support across the nation for solar power.

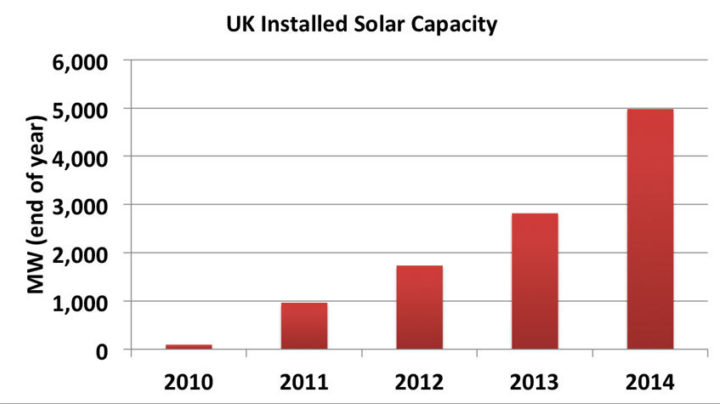

The ‘sweet’ taste for the solar industry comes not only from sustained public endorsement, but also from figures released by DECC this week showing that a record amount of solar capacity was installed during 2014. Total capacity almost doubled, in fact, to a smidgeon under 5 gigawatts (GW).

Add in the projection from the UN’s International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) that costs of solar power will fall by 40% in the next two years – on top of an 80% reduction since 2008 – and you can see why anyone involved in or keen on solar energy would be sporting a sunny smile this week.

It may be hard to credit under the grey skies of January, but even in the UK, solar is on course to be cost-competitive with fossil fuels around 2020, given stable policy. An industry once privately derided even by supportive ministers as a ‘subsidy junkie’ is set to kick the habit completely.

However… this particular silver lining definitely comes with a dark cloud, ready to rain heavy drops on the industry’s parade.

Changing climate

Come March, government support mechanisms for solar are changing – radically enough to alter the forecast from sunny smiles to glum grimaces.

Explaining why is a complex picture. I feel I should apologise for inviting you down this rabbit-hole, so tangled are the weeds; but don’t blame me – blame the policy wonks in DECC who appear to have constructed the current system under instructions to make it as complicated as possible and to break records for acronym invention.

So… projects larger than 5 megawatts (MW) in size – which are almost all ground-mounted ‘solar farms’ – are currently supported by the Renewables Obligation (RO) mechanism. But the RO is coming to an end, to be replaced by Contracts for Difference (CfD).

The CfD regimen is more complex and bureaucratic, and requires more up-front investment by the developer, involving higher risk.

This favours big companies. But the solar industry, where many companies are small, is uniquely having to make the jump now [pdf link] – two years before wind, for example, where companies tend to be larger and thus better suited to the CfD regimen.

There’s more. The government has capped the total amount of money available for low-carbon energy (under the Levy Control Framework), officially in order to protect the public purse from excessive spending on ‘green crap’, as it’s known in the corridors of Whitehall.

But last year it committed more than half of the funds available for the period up to 2020 to just eight projects – five offshore wind farms and three biomass schemes – for which it was roundly criticised by the National Audit Office. So there’s now less money left in the pot for everyone else, including solar installations.

Solar projects smaller than 5MW, meanwhile, are supported by yet another mechanism, Feed-in Tariffs (FiTs). Support comes in several bands, according to the size of the installation.

Small, household projects (of which the UK installed 125,000 last year) are likely to be ok. But intermediate-sized schemes, such as you might find on a large warehouse or business, are in a more difficult position.

Essentially, if more than 32MW capacity is installed across the country in a given quarter of a year – which could be six or seven large factory roofs, for example – the level of financial support falls. Success is penalised; growth is restricted.

As if all this financial stuff wasn’t enough, there are three more hurdles.

One is that installations require connection to the National Grid. In some parts of the country, the grid can’t handle more input without an upgrade.

A second is the decision by Environment Secretary Liz Truss late last year to remove farming subsidies from installations on agricultural land, despite DEFRA admitting it had no figures for the amount of farmland occupied by solar panels and despite evidence that livestock farming can co-exist very well with solar installations.

The third potential obstacle is planning. So far there’s no firm evidence that the Department for Communities and Local Government is deliberately blocking approval for solar farms, but it appears to be doing so for wind – and in this particular game, where the wind blows, the sun tends not to be far behind.

So here’s the rub for the UK’s solar power industry and the 80%+ of the population that supports it: at the very time when prices are falling and the end of subsidies is in sight, the conditions essential to complete the process and take the industry to a state of independent maturity are about to melt away.

Cross-party myopia?

Although opposition to solar is sometimes portrayed as a Conservative Party phenomenon, recall that this is a Coalition government and that the LibDems are in charge of DECC. Recall also that while Labour has fought the industry’s corner at times, it hasn’t come forward with anything approaching a coherent solar power strategy.

In fact, two connected people, one in the Labour hierarchy and one in the Conservatives, have whispered to me recently that the UK shouldn’t really bother investing much in solar.

The smart thing to do, they both said, is to let Germany keep supporting the technology until costs fall further, and then take advantage of all that German investment – much as the National Health Service trains fewer doctors and nurses than it needs, instead recruiting them from other countries that have paid for their training.

Not only does it seem a somewhat shameful strategy for any party that proclaims patriotism, but it's technically incorrect, given that the panels themselves make up a progressively smaller proportion of the overall cost as their wholesale price tumbles.

And here’s the really odd thing. In case you hadn’t noticed, there’s a General Election coming in just four months’ time. It’s likely that energy and climate change issues will be some way up the agenda, especially given today’s survey finding that climate change rates alongside crime and education on the list of public concerns.

The political research agency Dods recently polled MPs [pdf link] asking what they think their constituents would prefer in the energy field – solar, wind, shale gas or nuclear.

Both Labour and Conservative MPs reckoned their constituents would put solar energy as their number one choice – and judging by the public polls, they’re right.

So coming up with a sensible strategy to support the solar industry while it completes the final step of its de-subsidisation programme ought logically, to be a vote-winner.

It’s not just about panels on roofs and in fields, after all – this is about decarbonising the UK’s electricity supply.

The Committee on Climate Change reckons this ought to be more or less complete within 15 years, if the UK is to meet its legally binding target of an 80% emissions cut by 2050 - and the next five years are a crucial time for making investment decisions commensurate with decarbonisation. So whether solar soars or plummets from March onwards matters.

Compare the lack of focus on solar with the vast attention lavished recently on fracking, which the public opposes and which cannot play a major role in decarbonising the UK’s electricity system unless a coherent carbon capture and storage policy comes along, and – well, it’s mystifying.

Any bright ideas?

Share