North-South divide: More complex than it looks

Unravelling the compelling complexities behind 'justice' and 'fairness'

By Germana Canzi

Share

Last updated:

The opening day of the United Nations climate conference this week – including positive speeches from heads of state and other personalities – injected a major sense of hope that there will be an agreement at the end of the two weeks of negotiations.

But now that detailed negotiations have started, there are fears of a re-emerging divide between rich countries and poor countries as a key stumbling block. But does this divide really exist, or is reality – as is often the case – more complex?

And is the stumbling block actually about different interpretations rather than different principles?

Unravelling the terms

There are two key, related issues here, known as “climate justice” and “differentiation”.

Former UN High Commissioner on Human Rights Mary Robinson defines climate justice as rectifying the injustice faced by “communities most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change despite having contributed least to the cause”, through “swift and ambitious climate action, including reducing [global] emissions to zero as rapidly as possible.”

But dig deeper, and use of the “justice” term itself means different things to different countries, organisations and people. And it’s not just about climate change – the right of developing nations to develop is also inextricably linked.

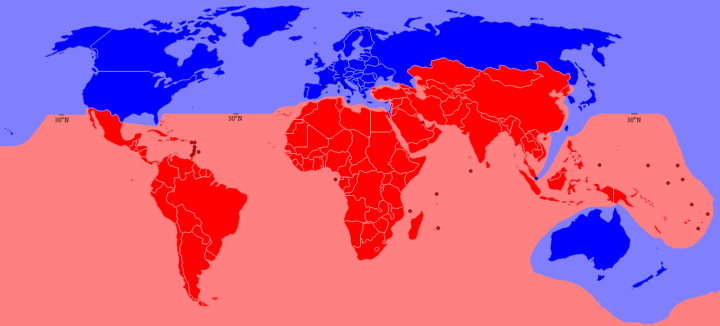

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been using the term “justice” to make a link to “differentiation”. Here, we hark back to the very beginning of the UN climate convention. The bureaucrats who drafted the text in 1992 divided countries along strict binary lines – rich and poor. Into the “rich” group went OECD members and the former Soviet bloc – into the “poor” bloc went everyone else.

The convention is quite explicit about the relative roles of rich and poor. The rich have to reduce emissions first, and to help poorer nations both adapt to climate impacts and “green” their economies.

The rich have more onerous responsibilities when it comes to measuring and reporting on emissions.

Even in 1992 the world wasn’t a binary place; and since then, it’s become even less binary.

“Poor” Qatar has a per-capita income about seven times higher than “rich” Romania; that’s an extreme situation maybe, but the “poor” Gulf states are nearly all in the top 30 countries for per-capita income, while many other developing nations including Malaysia, Israel and Trinidad & Tobago have overtaken the poorest in Eastern Europe. And per-capita emissions broadly follow per-capita GDP.

A world of blacks and whites?

So you might argue that the old binary model should be updated.

Indeed, that’s what some in the richer parts of the planet have been arguing. But developing world – as represented by the powerful G77/China bloc of nations - can legitimately point to a legacy of broken promises by the “rich”, and not all in the climate change arena. This means they instinctively cavil at any notion of an official blurring of the binary “differentiation”.

However, in the real world, boundaries are blurring by themselves. China, for example, has clearly moved on massively from its position a few years back. It has said it doesn’t want any of the climate finance owed by Western nations to the “poor”, and indeed will provide finance for the poorest from its own coffers. It has unilaterally taken to an emission-cutting pathway whose ambition exceeds that of most Western nations.

At the UN summit in South Africa four years ago, where governments decided to seek a new agreement by 2015, impetus came from a “rainbow coalition” of Europeans, small island states and Least Developed Countries, in opposition to a “coalition of the unwilling” encompassing the US, China and India. Both real blocs transcended the official ones.

And Brazil, that most diplomatically skilled of nations, has proposed a concept called “concentric differentiation” that would take account of how the world has changed already and of further changes in the year ahead.

Toxic decarbs?

Here in Paris, we see very real differences between the priorities of various developing nations. For example, the 40 or so countries that are members of the Climate Vulnerable Forum want both the developed and the developing world to move much faster to decarbonisation. In a declaration approved on Monday [pdf link] these countries are calling for 100% renewable energy by 2050.

In addition, Kiribati, a Pacific island for which even a good Paris agreement may come too late to stop its population from having to relocate, is calling for an immediate moratorium on coal mining.

This is diametrically opposed to the stance taken by a number of other developing nations, with India in the vanguard, who in public at least are planning coal investments that would push up warming well above the currently agreed threshold of 2 Celsius over preindustrial temperatures. (I say “in public” because as smart analysts realise, there is real-world evidence that many of India’s and other countries’ “planned” coal-fired power stations don’t actually get built.)

Meanwhile it’s rumoured that Arab nations will block any attempt to have a long-term decarbonisation goal in the agreement here, which couldn’t be more directly opposed to the position of the Climate Vulnerable Forum countries.

Starting where we are

Some campaigners attempt to square this circle intellectually by arguing that Western nations should decarbonise their own economies much faster and provide much more financial and technical support for poor countries. Taken to its full equitable extent, they argue this would allow both Kiribati and India to realise all of their ambitions.

If Western nations had embarked on radical decarbonisation 15 years ago and really led by example as they are supposed to under the climate change convention, that might be realistic. As it is, real-world politics (the US Senate, the new Polish government, etc) mean that for now at least, the odds of the US, Japan, the EU and the rest increasing the speed of their emission-cutting five- or 10-fold, say, are as unlikely as Donald Trump becoming a hippy.

One obvious way from this reality to a strong agreement in Paris is for Western nations to hold their hands up, admit they failed to lead sufficiently in years gone by, admit that they are now struggling to decarbonise their economies as quickly as science and justice indicate, and fulfill their pledges on finance fully and generously.

(Which is not to say they have good reasons for not hastening their own decarbonisation – quite the opposite. Analyses show that many can easily accelerate the transition to a low-carbon economy – first and foremost Britain and the European Union, whose plans don’t deviate much if at all from “business as usual” decarbonisation.)

It’s very notable in this context that India has said it will reconsider its coal expansion plans if the West comes to the table on finance – a proposal that, one hopes, is being taken very seriously by Western ministers and indeed anyone with an interest in seeing a strong deal emerge here.

There is little doubt that of all the issues that could block agreement here in Paris, “justice” and “differentiation”, connected, is the big one. In a technical sense, it extends into all aspects of the draft text – finance, loss and damage, the long-term goal for decarbonisation, monitoring and verification.

However, the real world is clearly more complex than official negotiating blocs pretend – fertile ground for discussion, debate and enquiry.

Share