When thinking the unthinkable is rational

A major new Foreign Office study issues warning on worst-case climate risks

By George Smeeton

Share

Last updated:

By Germana Canzi, ECIU International Climate Change Analyst

Generally, in one’s personal life, thinking about the worst thing that could happen is not a good idea. When we make decisions, it’s helpful to assume things will go well, in our studies, profession or in love. Even when confronted with serious illness, the general wisdom is that it’s best to ‘think positive’ about the outcome.

On climate change, the same is true to some extent. Contemplating the consequences of worst-case scenarios is the stuff of nightmares, and there’s evidence that when NGOs create spectral visions of planetary catastrophe, people look away. And of course there is still plenty that can be done to avert disastrous change.

A major report on climate change ‘risk assessment’ – launched yesterday at the London Stock Exchange by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office – found that in order to keep ourselves safe from climate change we do need to think about the worst that could happen.

It says that scientists need to do far more to analyse this possibility (they currently don’t). Even more importantly, politicians need to hear about this (they currently aren’t). Only by considering the worst risks can we make the best decisions.

Learning from other risks

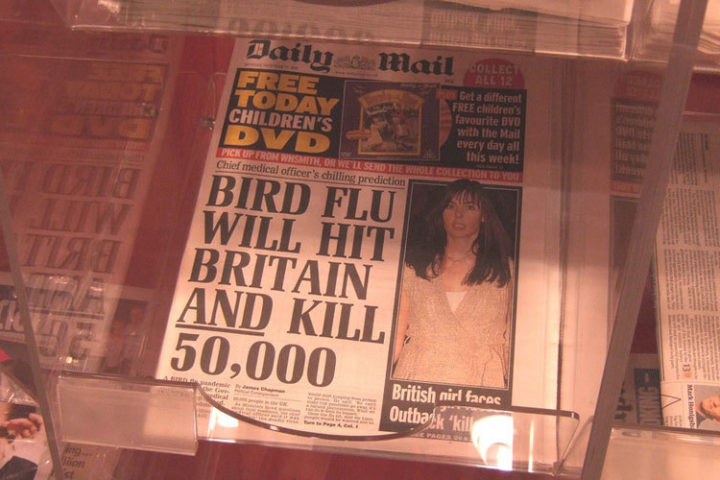

Potential health epidemics, national security and business risks are systematically assessed on the basis of the worst-case scenario.

The insurance industry is required by law to hold enough capital to cover liabilities that would arise from catastrophic events that are likely to happen only once every 200 years.

Japanese law requires buildings to withstand events that are only likely to happen once every 500 years.

When governments plan for a potential pandemic, they look at worst-case scenarios where millions could die, and avoid this happening through vaccination programmes, for example. There are many more examples.

The basic principle of risk assessment is to identify what we want to avoid, ask how bad that consequence would be, and then ask what the likelihood is of it happening. Just because something is unlikely, it shouldn’t be ignored if the outcome is potentially catastrophic – rather, it should be understood as fully as possible.

Then one needs to use best available information (and a best estimate is better than no estimate at all), and take a holistic view, looking at both direct and indirect consequences.

What’s the worst that can happen?

The point is particularly pertinent to climate change, with impacts forecast to become more serious over time and with some impacts looking far worse if we pass critical thresholds. Looking at the worst-case scenario also means acknowledging and assessing the worst risks likely to be present at the highest degrees of increase above preindustrial temperatures.

But by and large this is precisely what scientists and policymakers have not been doing.

If carbon emissions carry on as they are, and nothing at all is done, temperature increases of over 10 Celsius over the next few centuries cannot be ruled out. However, most of our scientific knowledge – and much of the political discussion, media coverage and negotiations around it – relates to the risks of much lower degrees of temperature increases of 2–4C.

Why have we had this rather truncated, limited discussion?

One reason is that what happens to the world at a lower end of warming is easier to analyse.

Some also suggest that the success of the climate sceptic version of ‘facts’ on climate change (i.e. that it’s not happening, just a big conspiracy) and its influence over parts of the media mean that many scientists are worried about being accused of scaremongering.

As a consequence, they are overly cautious about what kind of issues they research and what they say publicly.

But if on health, security and financial risks experts actively look at all ranges of probability of something awful happening, including worst-case scenarios, why should we not do that with climate change?

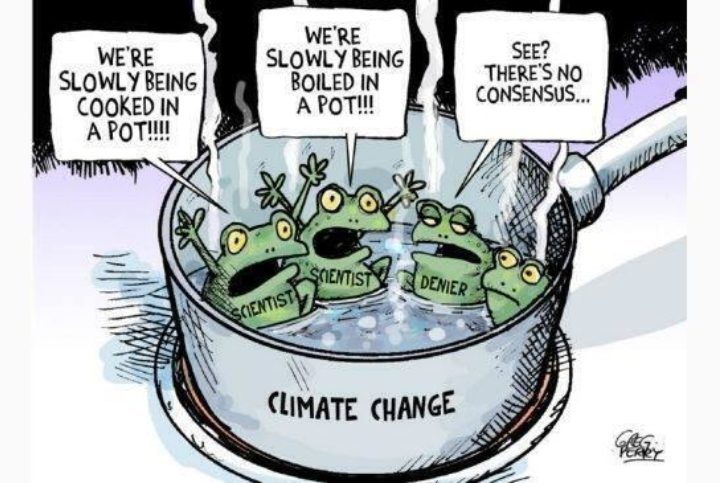

The UK government’s international representative on climate change, Sir David King, graphically illustrated the point with a story about a frog in a pan on the fire.

If a scientific adviser tells the frog that it will start to warm up in two minutes, that may make the frog complacent, even looking forward to a nice warm bath. Sound advice would however be to tell the frog that if it stays in there for five minutes, and nobody puts out the fire, it will die.

Protecting for survival

The most important political decision to be made about climate change is how much effort to expend in countering it.

Politicians need to know, for example, that a temperature increase of 4C or more could pose very large risks to global food security because many crops have limited tolerance for high temperatures.

Similarly, people die of heat stress in heat waves (and thousands died this year in India and Pakistan) but this currently tends to affect mainly the most vulnerable, elderly or those working outside in the heat. If temperatures increase 5-7C above preindustrial temperatures, it starts to become likely that hot places will experience conditions that could kill even healthy people. And it’s unlikely that air conditioning will be accessible to all.

The FCO’s climate risk report makes for rather worrying reading.

But the authors stress it’s important not to become fatalistic after reading it, or think that it’s all hopeless. Just as small changes in climate can have very large effects, the same can be true for small technological, financial or political changes.

The risks from climate change may be greater than is commonly realised, they emphasise – but so is our capacity to confront them.

Share