Big oil and the Paris Agreement – is it all gas?

How are the world's largest oil companies preparing for global action on emissions?

By Jonny Marshall

Share

Last updated:

By Dr Jonathan Marshall, ECIU Energy Analyst

As the world pats itself on the back for pushing the Paris Agreement into action, and therefore implementing the first global attempt to reduce emissions, some of the world’s most valuable companies may be starting to look over their shoulders.

Seven of the largest oil companies are set to announce the formation of a renewable energy fund on Friday, the same day that the Paris Agreement comes into effect. While this is undoubtedly a step in the right direction, the world needs more clarity on how well this will be financed, what its targets are and how it affects the business models of some of the worlds most polluting companies.

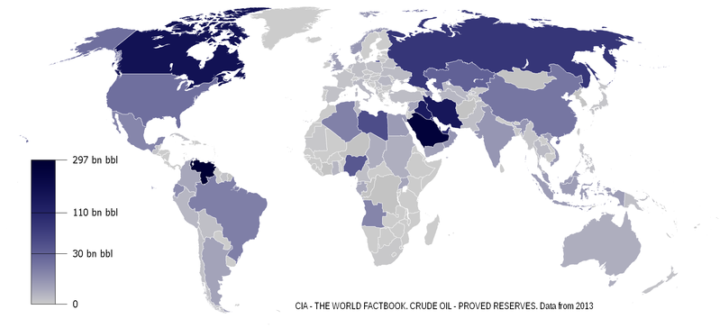

Half of the world’s ten most valuable companies earn their income from fossil fuels. Add onto this Saudi Aramco, which could be worth $2.5 trillion, and there is a serious amount of capital, investment and retirement portfolios dependent on the black stuff.

The business model of these companies: find oil, extract it, refine it and sell it to someone who burns it, is incompatible with the goals of the Paris Agreement. The deal, coming into force on November 4th, has been signed by 192 coutries and ratified by 89 within a year of it being agreed. Those 89 countries account for 63% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Under the Paris Agreement, governments pledge to:

- Keep the global temperature rise since pre-industrial times “well below 2°C”, and pursue efforts to limit it to 1.5°C

- Peak greenhouse gas emissions “as soon as possible”, with developed countries taking the lead (as has been a principle of the UN climate convention since its origin in 1992)

- Achieve net zero emissions in the second half of the century (which involves, among other things, reducing fossil fuel burning close to zero)

The scientific rationale for the Paris Agreement comes from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which published its Fifth Assessment Report in 2013-14. Its key conclusions – which all governments accepted – include:

- Under current emissions trends, global warming is likely to exceed 2°C. By the end of century, with “business-as-usual” emissions, the global average temperature is forecast to be 1.9-5.3°C above pre-industrial times

- Continued emissions of greenhouse gases will cause “long-lasting changes in all components of the climate system, increasing the likelihood of severe, pervasive and irreversible impacts for people and ecosystems”

- Keeping the temperature rise below 2°C entails bringing fossil fuel emissions to zero by or shortly after mid-century

Scientific research shows that continuing to burning coal, oil and gas at current rates is incompatible with the Paris Agreement and with the science of a 2°C target.

1. How much coal, oil and gas needs to be left in the ground?

- For a 50% chance of keeping global temperature rise below 2°C, total CO2 emissions between 2011 and 2050 need to be kept below 11 Gigatonnes (billion tonnes) (11 GtCO2)

- From 2011 to 2015, around 10% of this ‘carbon budget’ was consumed.

- If extracted and combusted, current known fossil fuel reserves would emit three times this amount of carbon dioxide.

- Around one-third of oil reserves, half of gas reserves and 80% of coal must remain unburnt to meet the 11Gt target.

- Any increase in unconventional resources (such as shale or tar sands), or Arctic production, reduces the amount of conventional oil and gas that can be burned.

- The development of carbon capture and storage (CCS) would give producers more room to extract reserves, but would not give carte blanche to burn all known resources.

2. Oil companies have in the past advocated two policy measures to combat climate change: a global carbon price, and carbon capture and storage:

- Economists have been urging for the introduction of a global carbon price for at least two decades, without any sign that it is going to become reality

- The biggest carbon pricing system in the world, the EU Emission Trading System, prices carbon far too cheaply to incentivise decarbonisation. The price is typically around €5-6 per tonne, whereas the OECD says that €30 (£27) per tonne is needed to cut emissions

- 70% of global emissions are priced at zero, with only 4% priced above €30 per tonne

- Oil companies including Shell and BP use an internal carbon price of about $40 per tonne, but only applies this to their own operations (gas flaring etc), rather than products sold

- BP, Total and Eni have previously lobbied against increased carbon pricing, and called for an increase in free allowances.

- Multiple analyses, including by the IPCC, indicate that carbon capture and storage is logically a core technology to deploy for keeping global warming below 2°C

- CCS works by capturing CO2 when produced in power stations or industrial facilities, transporting it by ship or pipeline, and burying it in safe underground storage

- It cannot be used for transport (a quarter of emissions, almost all from oil) or home heating

- Shell says a carbon price around $60-80 (£49-£65) per tonne is needed to develop CCS

- No major oil or gas company is implementing CCS beyond R&D scale

3. Some questions and issues

Based on these findings, have fossil fuel companies changed their business models to account for governmental agreement on net zero emissions within 50 years?

Spending on exploration between 2015 and 2020 fell by 22%, largely due to the fall in oil prices. Have upstream development budgets changed since the Paris climate summit?

Given their backing for a global carbon price, what are oil companies doing to bring it about after 20 years of failure?

Seven oil companies are set to announce the creation of a renewable investment fund on Friday. What will the value of this fund be? For comparison, the combined 2016 budget of the six publically traded companies taking part in the scheme is more than $85 billion.[1]

What carbon price would oil companies advocate?

Despite producing a 2°C scenario, Shell has “no immediate plans to move to a net-zero emissions portfolio over our investment horizon of 10-20 years”

Analysis of BP’s latest Energy Outlook shows little recognition of the Paris Agreement, with economic factors only seen to dictate changes in forecasts – overall energy use, and oil and gas demand, were seen to be unaffected by the global climate deal.

[1] Figures accrued from company accounts. 2016 Eni budget assumed to be one quarter of planned 2016-19 budget.

Share