Whatever happened to the 'hidden costs' of renewables?

Report slays canard that solar energy's variability adds massive amounts to its price tag

By Richard Black

Share

Last updated:

On Tuesday, after reading Aurora Energy Research’s report on the costs of adding solar power to the grid, I tweeted that I’d just read the most important energy story of the day.

After a bit more thought, I’m upgrading. I’ll name it as a contender for the most important UK energy story of the year.

That might seem like a bold claim given all the shenanigans of the Hinkley Point C power station, which really ought to get a mini-series of its own wherein a bare-chested Ross Poldarkian George Osborne woos French and Chinese maidens simultaneously and manages to hand both safely into the care of the new Lady of the Manor even at the moment of his downfall. Not to mention approval of Lancashire fracking applications, the decline of North Sea oil and gas, National Infrastructure Commission endorsement of the smart flexible low-carbon grid...

So let me try to justify the claim.

Repeated analyses from both national and international bodies shows that for most countries, there are three absolutely core steps necessary for eliminating carbon emissions – the long-term goal to which all governments committed themselves under the Paris climate change agreement.

- Make the use of all energy as efficient as possible

- Decarbonise the electricity system

- Extend the use of electricity to sectors where currently, fossil fuels are burned directly, such as heating and transport.

There are basically three options for building a low-carbon electricity system: nuclear reactors, renewables, or fossil fuel plants with carbon capture and storage (CCS). Each comes with its own set of issues and costs; and in the case of renewables, the key issue (and it’s a serious one) is that for wind turbines and solar panels, generation isn’t continuous.

This means that additional measures are needed to keep the lights on – and they cost extra money.

Among 'brown movement' think-tanks and other organisations opposed to reducing carbon emissions, these ‘hidden costs’ have emerged as a totemic argument against renewable energy.

The pre-Brexit Cabinet flirted with it pretty heavily too.

Then Energy and Climate Change Secretary Amber Rudd’s department briefed the Mail on Sunday last August that she’d commissioned a study from the consultancy Frontier Economics that would tot up these hidden costs, with a DECC source adding ominously: ‘Many in the energy industry have suspected that previous governments have been “economical with the truth”’ about the economics of a low-carbon transition.'

Then, when Ms Rudd delivered her long-awaited ‘reset speech’ in November, she announced that renewable generators would be held ‘responsible for the pressures they add to the system when the wind does not blow or the sun does not shine’.

More than a year on, that Frontier Economics report has yet to be published. Insiders in the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), which inherited DECC’s responsibilities, say it’s tucked away in a drawer somewhere while civil servants decide what to do with it.

Cost becomes benefit

Into that vacuum steps this week's Aurora report. And its conclusions are fascinating.

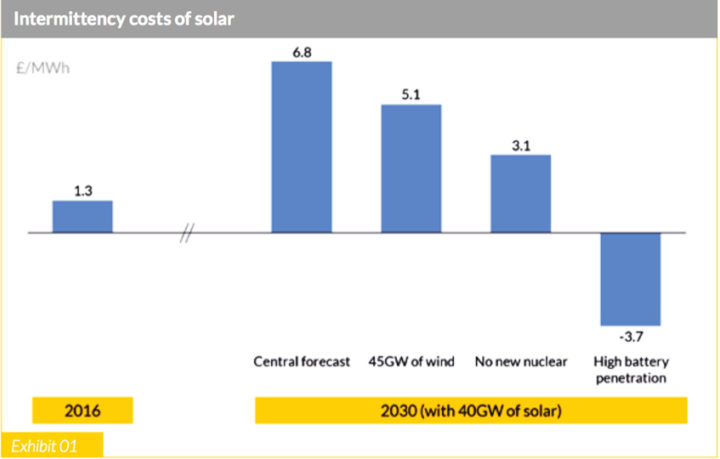

Aurora concludes that currently, solar power’s ‘hidden costs’ in the UK amount to £1.30 per megawatt hour (MWh). That hikes the total cost of solar by less than 2%.

As a technology devoid of fuel costs, the more solar generation you add, the further the wholesale electricity price falls. But there’s a limit, because after a while, you’re adding something virtually free to something that’s already very cheap; so the additional costs rise faster than the additional benefits.

Aurora concluded that having 40GW solar capacity on the grid by 2030 would, net, carry a higher additional cost than currently – £6.80/MWh.

Even at this pretty high (but doable) level of solar capacity, we’re below the estimate of the Committee on Climate Change, the government’s statutory adviser, which recently put the ‘hidden cost’ of renewables at about £10 per MWh.

But now we get to the really interesting bit. Aurora next modelled the ‘hidden costs’ if you also have 8GW of battery storage on the grid by 2030 – again, a realistic estimate – in addition to the 40GW of solar capacity.

Now, the ‘hidden costs’ disappear, becoming a ‘hidden benefit’ – saving £3.70 per MWh.

The reason why is, at top level, pretty simple. Neither the traditional baseload-heavy model of electricity generation nor the new flexible one based on the variable output of wind turbines and solar panels generates in a way that matches demand; in the old model, you simply turn generation off or on in order to match demand, in the new you rely on various flexibility mechanisms including storage. Both of these solutions have hidden costs.

Introducing batteries to store and release solar-generated electricity brings flexibility that eases the process of matching supply to demand – and in doing so, turns the ‘hidden cost’ of 40GW of solar capacity into a hidden benefit.

At the Helm

Now: forecasts are forecasts, models are models. No-one has to believe them. Some will point out that the Aurora report was commissioned by the Solar Trade Association, the trade body for the UK solar industry, and will distrust it on that basis.

To which the response would be that Aurora’s USP is its credibility and rigour. And it’s not any old company; among its directors is Dieter Helm, the Oxford professor who’s widely regarded as the Treasury’s favourite energy economist.

In terms of overall economics, the Aurora study doesn’t include the costs of batteries themselves – which are declining, but still significant – nor the costs of erecting the solar panels. It doesn’t look at the simple technique of encouraging solar farms to point panels east and west, rather than south, in order to spread generation across the day. So it’s not a complete picture.

But it does appear to slay the canard about hidden costs axiomatically being high pretty effectively.

One presumes, therefore, that Dieter will be sending his company’s study to the House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee for incorporation in its current inquiry into the economics of UK energy policy, as an update to the oral evidence he gave earlier in the year.

Given that the inquiry’s remit includes asking ‘What are the emerging technologies which could materially change the energy market over the next decade and beyond?’, and that he highlighted hidden costs during that evidence session, saying of renewable energy providers that ‘It’s always in their interests to not pay the system costs of what they’re doing’, you’d certainly consider it pertinent.

As for the (by now dusty) Frontier Economics report, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that DECC didn’t publish it because its conclusions were broadly in line with Aurora’s – which didn’t fit the government’s narrative of cracking down on renewables build.

Story rank

So back to where we came in: the most important energy story of the year? Well; for all the movements in oil and gas, the big political conversations and the big investment decisions currently focus on electricity. As outlined earlier, if the government's aim is to meet legally-binding carbon targets, power sector decarbonisation within 15 years is essential – non-negotiable.

The issue is, how is the UK going to do it?

Uncertainties over renewables, with the ‘hidden costs’ of grid balancing to the fore, were among the factors that led to Hinkley Point C. It’s one of the issues, though not the biggest, preventing restoration of onshore wind where public opinion allows.

So, knowing that ‘hidden costs’ can be hidden benefits is kind of important. (It's worth mentioning that the two other low-carbon flexibility mechanisms, interconnectors and demand response, also bring costs down.)

But the key takeaway from the Aurora report is this: you have to do the economics by looking at the system, not at individual technologies. The smart, low-carbon flexible grid, as advocated by the National Infrastructure Commission and EnergyUK just this year, is a system – not a bunch of random technologies. I don’t particularly care how much the indicator lights or the hubcaps or the aerial on my new car cost – but I do care about the price of the whole thing.

So, the most important energy story of the year? Oh alright then – maybe not quite. Top five, though, without doubt. Even without George as Ross on the cover.

Share