On the road to find the magic money tree

To achieve net zero — by 2050, 2045 or 2030 — tree and transport policies have some growing up to do.

By Matt Finch

Share

Last updated:

There was a dizzying array of (future and potential) climate change policy announcements at the recent party conferences. By far the most eye-catching was the announcement that, if in power, Labour would (try and) ensure that the UK will be emitting the same number of carbon emissions in 2030 as it’s sequestering. To get this done, a 'Green New Deal' - that is, a massive state-led programme of green investment - would be implemented. The year 2030 is ambitious, as is the current enshrined-in-law (and also, therefore, current Tory policy) date of 2050. The Lib Dems want to bring the date forward to 2045.

To get to net zero though, a whole raft of 'sub' policies are needed, and there are three sectors that all parties recently focussed on. My colleague, Jonathan Marshall, has commented on the Future Homes Standard, so let’s look at the other two: trees; and transport.

Trees

The Tories announced that they will plant one million trees between 2020 and 2024 (so 250,000 per year) in Northumberland — the 'Great Northumberland Forest'. Furthermore, they will also create 'pocket parks' on disused areas of our towns and cities (it remains unclear whether this is in addition to the one million trees supposedly being planted in our towns and cities right now, which was a commitment in the Tory 2017 General Election manifesto…)

Some context will help here though. There are an estimated three billion trees currently in the UK: 47 for every person. To put this itself into context, there are an estimated three trillion trees globally, or 422 trees per person. This means that 250,000 trees equal just 0.0083% of the UK's tree stock. As it stands, 13% of the UK is covered in woodland, and the Committee on Climate Change would like this to rise to 17% to help achieve net zero. If we assume uniform growth, then that 4% equals an extra 923m trees. So, the question for the Tories is this: where will the other 922 new forests go?

Of course, this is not just a question for the Tories. Labour promised to 'Implement a programme of ecological restoration to increase biodiversity and natural carbon sequestration', and the Lib Dems promised it would be 'Increasing UK forest cover by planting an additional 60 million trees a year, and by restoring peatlands.' The Lib Dems are in the right ballpark when it comes to the number of trees needed, and the Tories have at least identified one future area of woodland. But the major unanswered question, for all parties, is what policy mechanisms to use in order to dramatically ramp up tree planting. And to state the blindingly obvious again, where will these new trees go?

Transport

The main battleground, however - and therefore the sector with the most developed policies - is the transport sector. From an emissions perspective, this makes sense: surface transport is the largest emitting sector of the UK, accounting for 23% of all emissions.

This time, it’s the Labour party that has made the biggest commitments, including: some £3.6 billion for a huge expansion of the charging network; making interest-free loans available to prospective EV purchasers (which already - successfully - happens in Scotland); and, a scrappage scheme (full details here). The party will also stoke demand for EVs by converting the entire Government fleet to fully electric by 2025, and putting 30,000 electric car club vehicles on the road. Both Labour and the Tories have pledged that the UK will have its very own gigafactory (Mr Johnson did so in his closing speech. Labour, meanwhile, pledged £2.3 billion to get three built). The UK currently has 0.8% of the worlds lithium-ion production capacity, which clearly needs to increase if the UK Government wants the UK to manufacture more than 0.8% of the world's cars (although it should be noted that the UK only produced 1.6% of the world's cars last year anyway - 1.5 million out of 98.1 million). Furthermore, Labour has pledged to invest £500 million into four rare-earth-metal recycling plants.

The Tories have not been as specific, but have pledged 'up to £1 billion' (question: why 'up to'?) to 'accelerate production of key technologies.' The Tories have also pledged to review the unambitious 2040 ban on new combustion vehicle sales, with the goal of bringing it forward (Labour have no need for such a ban, as its 2030 net-zero date encompasses all combustion transport). The Lib Dems would start its ban in 2035.

Yet again, we’re left with outstanding questions. For instance, there is loads of stuff about cars, but next to nothing on vans or HGVs. But the big question is simply, is this enough? All parties are in fact trying to achieve two things with their respective EV policies: 1) move the UK’s transport fleet to an electric version as quickly as possible, and 2) protect, and even enhance the UK’s indigenous car industry. Labour has pledged north of £6 billion for these twin aims, which seems impressive, but is dwarfed by the $136 billion being invested in China, the $72 billion being invested in Germany and the $34 billion being invested in the US.

Regardless of the questions, from an environmental point of view, these policies are all heading in the right direction. But there is another huge reason why a quick transition to electric vehicles - and indeed away from all fossil fuels - would be desirable. Because it would make the country richer.

Investment

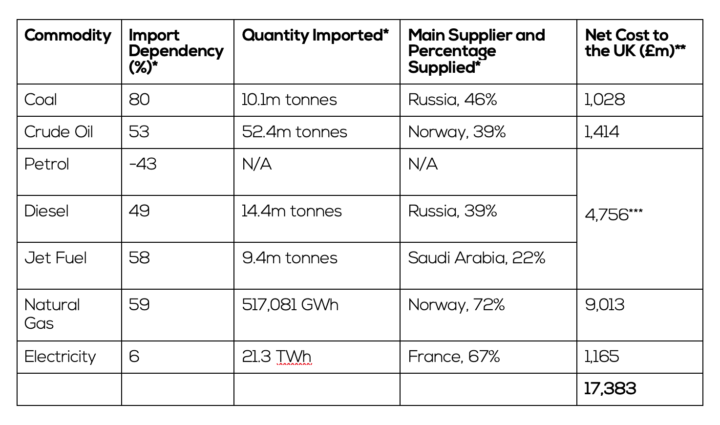

Inevitably some of the immediate media reaction has focussed on the financial challenge of meeting any parties’ net-zero target. Indeed, the-then-Chancellor, Philip Hammond, wrote a letter to the-then Prime Minister, flagging this. Yet, somewhat predictably, there has been little made of the costs that will be saved. They are eye-watering. It is a rarely mentioned fact that 36% of the energy used in the UK is imported (2018 figures), costing the UK £17.3 billion.

In fact, it seems the UK imports pretty much anything associated with emissions: amazingly, we also import wood pellets from the USA to burn for electricity, and peat from Ireland for compost. So, if last years figures are indicative (which they are), moving the economy to a position where it creates and uses all its own energy saves the UK £17 billion. Every year. Forever. And it also completely allays any energy security fears that currently exist. (Should we not be worried that half the diesel we use comes from abroad? What about the 59% of imported gas we use to heat our homes?)

In this respect, moving to net zero must be viewed as an investment, and a no regrets one at that: the simple fact is, all things being equal, a net-zero UK is also an energy-secure and richer UK. Crucially, the £17 billion does not disappear. Instead, it remains in the UK economy, providing a £17 billion annual boost (and let’s be blunt: since electricity is so cheap compared with oil, individual drivers would have more money in their back pockets, too). This is surely the reason why all parties are now pushing a rapid EV rollout? And whilst trees obviously take time to grow, could some of today’s saplings provide electricity in years to come? Most importantly, just what could this country do with £17 billion extra each and every year?

** Data from DUKES: foreign trade statistics

*** Data for the petroleum products are combined. This means that despite the UK being a net exporter of petrol, this is far outweighed by the imports of other petroleum products.

Share