Ambitious Ethiopia needs UK to deliver at COP26

Prof. Yacob Mulugetta discusses why Ethiopia's policy makers, civil society and citizens expect the UK to deliver at COP26

By Kathy Grenville

Share

Last updated:

Ethiopia’s carbon footprint is small compared to developed nations such as the UK, contributing around 0.3 per cent of global emissions.

When we consider emissions in per capita terms, the difference is even more marked. The average Ethiopian has a CO2 footprint 35 times lower than that of the average Briton and a hundred times less than the average US citizen. While basic services for many, such as electricity, are yet to be met.

However, despite Ethiopia’s small carbon footprint, it has a credible track record of taking its climate commitments seriously.

In 2010, Ethiopia launched its growth and transformation plan (GTP) that would take the country towards becoming a middle-income status economy, boosting agricultural productivity and industrial development.

The following year came the Climate Resilient Green Economy (GCRE), which aims to keep emissions low and build climate resilience, as a basis for the country’s Nationally Determined Commitment (NDC) to the Paris Agreement.

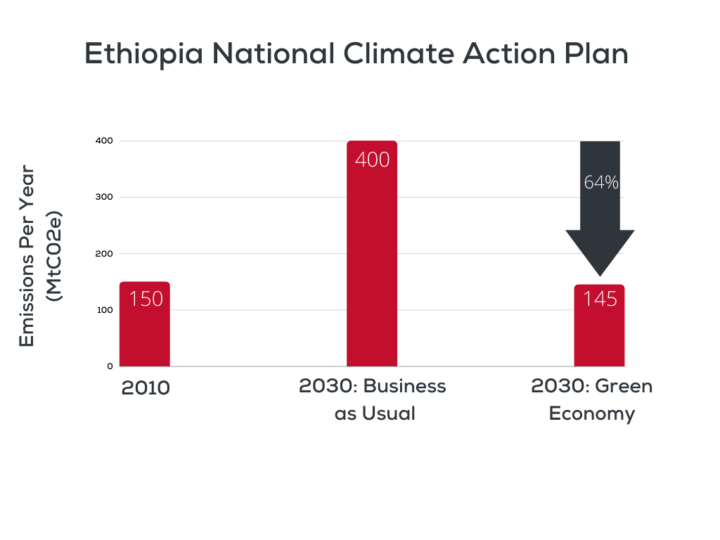

And while many countries took their time to deliberate the consequences of signing the Paris Agreement, Ethiopia was decisive and was among one of the first signatories, committing to cut its emissions by 64 per cent from business-as-usual emissions by 2030.

Why is Ethiopia - a country with a small carbon footprint - committed to reducing emissions?

Ethiopia’s ambition has surprised many who question why the country would think about committing to reducing emissions which are already comparatively low. For Ethiopia, committing to emission reductions and working towards a green economy makes sense for its development and progression as a country.

For example, the quest to enhance nature is seen as part of the journey to pursue development and poverty reduction. The raison d’etre of the CRGE is rooted in the country’s need to prevent a further decline of ecological services upon which livelihoods depend and to harness the country’s vast natural resources in ways that are sustainable.

Ethiopia has devoted significant resources to harness its renewable energy resources, establish rail infrastructure that runs on electricity from renewables, as well as engaging in one of the largest forestry programmes in the world. Programmes, such as these, are built on a strong ethical foundation of ensuring these actions also deliver significant benefits for its citizens.

Ethiopia’s drive therefore for green and sustainable development – as articulated in the CRGE strategy, its ambitious New Electrification Programme (NEP) and a number of other resilience initiatives - is based on the realisation that green growth is an opportunity, not a constraint, for low-income countries.

What does Ethiopia expect from the UK presidency of COP26?

The IPCC special report on 1.5°C has reinforced that time is running out to keep global temperature below 1.5°C, compared to pre-industrial levels.

Another recent report from the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services serves as yet another wake-up call.

Ethiopia is vulnerable to many of the effects of climate change. For example, the survival of Arabica coffee, indigenous to Ethiopia and the backbone of its economy, is highly dependent on the microclimate and local habitat. Rising temperatures and decreasing rainfall threaten Arabica coffee with extinction, raising concerns for millions of farmers who depend on it for their livelihoods.

For a country like Ethiopia where the majority of the population are subsistence farmers, going beyond 1.5C of warming would spell disaster as the very basis of their livelihoods would be compromised. Indeed, farmers in rural Ethiopia and elsewhere in Africa and South Asia have been adapting to a changing climate for many years now.

The message from vulnerable communities in Ethiopia, communicated through their governments and civil society organisations, is loud and clear: the world needs to get serious in taking action at home to show responsibility and build partnerships to foster genuine global solidarity towards a common agenda to address the climate challenge.

We have witnessed in recent weeks how rapidly the world was able to act to prevent economic collapse caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Significant resources were mobilised in a matter of days, amounting to $9 trillion with more promised in the coming weeks.

As we work ourselves out of the current pandemic, going back to the pre-COVID-19 era would amount to a missed opportunity. COP26 must aspire for more. We must also embrace the opportunity to plan for a longer-term recovery that eliminates poverty and build more resilient low-carbon economies and societies.

It means the same level commitment and effort showed at the height of the COVID crisis would be needed in terms of finance and technology transfer to enable transitions that are just and inclusive. COP26 could be about setting an inspiring vision about the future, and the UK government has a responsibility to seize this historic opportunity.

Ethiopia’s and Africa’s policy makers, civil society and citizens expect nothing less…

Share