Sustainable Development Goals marry energy and climate concerns

UN development summit is step towards global climate change deal in Paris

By Germana Canzi

Share

Last updated:

By Germana Canzi, International Climate Change Analyst

Those of us who spend most of our working lives sitting at a computer will perhaps find this hard to picture, but nearly one in five people on the planet has no access to electricity.

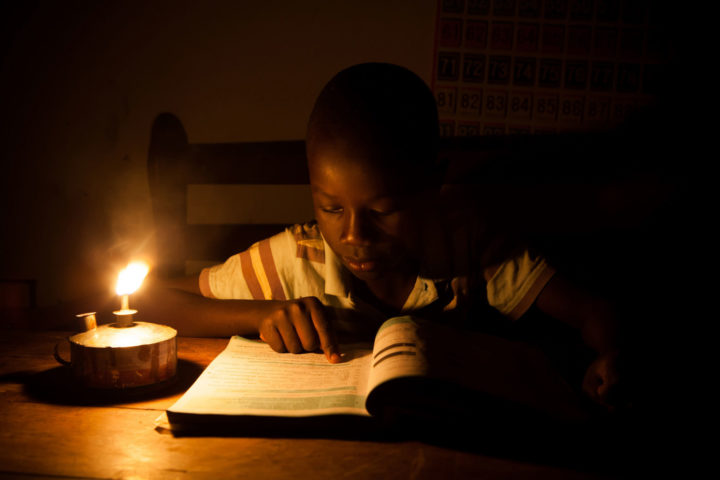

Billions of people can’t take the things that we do for granted: kids doing their homework in the evening, a fridge to store food or medicine, giving birth in a safely and brightly lit room.

In addition, almost three billion people rely on wood, coal, charcoal or animal waste for cooking and heating. Women and young children are exposed daily to indoor air pollution that causes serious diseases – this is among the reasons why millions of children die every year before they get to the age of five.

Throw in comparable statistics for access to healthcare, education, clean water and modern sanitation, and you are halfway to compiling a list of reasons why world leaders are heading to New York this week to finalise a new plan for helping and people out of poverty and keeping them there – the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (PDF).

The SDGs are designed to build on the successes of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Agreed in the year 2000, mostly with targets for 2015, the MDGs have helped achieve major poverty reduction, including a great drop in maternal and infant mortality, in the developing world.

But what the MDGs failed to do was to marry the drive for progress on poverty and health with protection for the environment – which is where the SDGs come in.

Climate change (goal 13), sustainable consumption and production, sustainable use of natural resources and ecosystems are all firmly in the goals, as well as the need for industrialisation, economic growth and cities to be ‘inclusive’ and ‘sustainable’.

The rationale is both simple and obvious: continued growth and progress need a healthily functioning natural world. This notion has been acknowledged, after all, since the Brundtland Commission released its seminal conclusions in 1987, but has yet to take root in all capital cities and boardrooms.

Cameron’s ‘people-centered and planet-sensitive’ agenda

The UK has been influential in developing the SDGs – not least through David Cameron’s co-chairing of the UN High-Level-Panel of Eminent Persons, which in 2013 set out principles for how development should function after 2015.

In the Panel’s words, the ‘people‐centred and planet‐sensitive post‐ 2015 agenda will need to be grounded in a commitment to address global environmental challenges, strengthen resilience, and improve disaster preparedness capacities. A more stable climate, clean atmosphere, and healthy and productive forests and oceans are just some of the environmental resources from which we all benefit.’

Thus Mr Cameron and his fellow Panel members put paid to the backwards-looking version of poverty alleviation that sees environmental protection as a hindrance.

Yet despite decades of sound evidence from the real world and from academia, that notion – environment or development? – stubbornly endures in certain quarters.

And nowhere does it endure more noisily than in the energy arena.

Throwing coal on the fire

From the perspective of the World Coal Association, bringing modern forms of energy to the billions currently without it cannot be done without fossil fuels. The argument goes like this: because China has recently lifted millions out of poverty precisely thanks to coal, then this is what’s needed for the rest of the developing world.

The key problem with this argument is that a big increase in coal use is incompatible with tackling climate change. And as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (among others) has clarified, unrestrained climate change threatens to reverse much of the progress made by developing countries in reducing poverty over the past few years.

But even disregarding this not so minor issue, there is another problem. As Ilmi Granoff of the Overseas Development Institute points out, boosting coal growth in developing countries could still leave 1 billion people without electricity and 2.5 billion without clean and safe cooking by 2030 because it will not meet the needs of energy-poor households.

According to the financial think-tank Carbon Tracker, only 7% of those without suitable access to energy in Sub–Saharan Africa live in the (very few) countries with coal assets. This would make it extremely expensive to hook up the rest to a centralised electricity grid powered by coal. Even in urban areas, where there is already a grid, the cost of renewables is often lower compared to coal generation.

The International Energy Agency would agree, judging by last year’s Africa Energy Outlook. Noting that old and dodgy transmission networks are a problem in most of the continent, it argues that renewables should account for about half of the extra energy access provided to 2040 – much of it grid-free, with villages powered by solar, wind or small hydro.

In India, a large amount of coal electricity generation has been added to the grid over the past decade, yet rural poor still remain largely without electricity, as do around six million urban households. Prime Minister Modi has recently branded solar energy as the ultimate solution to India’s energy problem.

The cost of renewable energy technologies has dropped dramatically over the past five years. Given the rapid improvements and cost reductions in storage technology and the rise of so–called mini-grids, developing countries now have a major opportunity to leapfrog into a decentralised, flexible and clean energy future.

There could be no better demonstration of this than the commitment of both China and India to install 100GW of solar electricity capacity, by 2020 and 2022 respectively.

Twin peaks

Historically, economic growth has gone hand in hand with a growth in carbon emissions, so the persistence of the old paradigm is in one sense understandable. But the world is changing fast; and the approval of the SDGs is an important sign that world leaders know that truly sustainable development means changing course.

Looking at goal 7 – to ‘ensure universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services’ – can help understand what it means in practice.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, China’s president Xi Jinping and even Pope Francis will be in New York this week for the agreement of the SDGs. The meeting is also an important step towards reaching a global climate change agreement in Paris later this year: a number of key national emission commitments are likely to be announced there, including India’s.

Given the proximity of the two summits, leaders will obviously want to be consistent in what their governments say from one to the next. So in New York, expect energy access and climate solutions to be on the same page, cheek by jowl, just as the IEA says they are in the villages of Africa.

Share