In hot water: Coal takes a plunge

2016 was a startlingly bad year for the coal industry, with record power station closures and a massive building slump

By Richard Black

Share

Last updated:

By Richard Black, ECIU Director

Remember when China was building a coal-fired power station every week, India was trying to follow suit, and prospects of curbing climate change looked as slim as a supermodel after Lent?

As the old song goes, time changes everything. It's certainly changed the outlook for coal.

Exactly a year ago we published a report on the unreality field around coal-burning in Asia.

'Unreal' because on the one hand, China, India and every other nation had just signed up to the Paris Agreement. Many had also established national policies that clearly aimed to constrain emissions markedly. Evidence was growing that China and India had both built more coal-fired power stations than they needed. And auctions for solar and wind power were seeing prices plummet to levels considered unrealistic just a few years previously, clearly coming in cheaper than fossil-fuelled generation in an ever-expanding list of nations.

On the other hand, some people, such as Nigel Lawson, were still claiming publicly that China and India were building thousands of coal-fired power stations - hence, for small nations such as Britain to cut their own emissions would be as useful as curbing one's flatulence in the middle of a hurricane.

As China and India together accounted for about 85% of the coal-fired power stations built during the previous decade and about two-thirds of those then planned, the facts clearly mattered.

Boom to bust

When we looked into it, it was clear that the Lawsonian narrative was badly out of date.

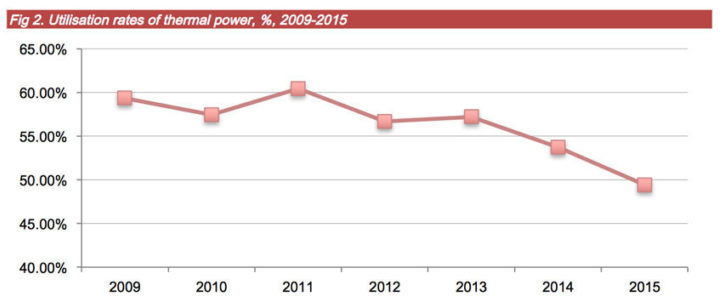

Our report showed massive and increasing over-capacity in both the Chinese and Indian electricity systems. New Chinese coal-fired power stations coming onto the grid were being used for less than half of the time, with Indian usage rates at 65% - and both were falling. In fact, China was burning less coal than two years previously, despite having built more than 100 additional power stations in which to burn it.

Business logic predicts only one outcome, and we forecast that new Asian coal-fired power stations would be built by the hundred, not the thousand.

Now, even that figure looks like it might be a huge overestimate.

Today, the latest edition of the Coal Boom and Bust report shows a massive contraction of ambition, in Asia and further afield:

- Globally, the number of coal-fired power stations in construction during 2016 was two-thirds down on 2015. Yes, that's right - a 62% drop. In a single year

- Looking at the number of plants in pre-construction phase (eg, planning and permitting), that was down by approximately half (48%) from 2015

- The number of planned plants being put on hold globally more than doubled

- In China alone the number of new plants being given permits sank by 85%

- And across the world, 64 gigawatts (GW) of coal-fired capacity closed - mainly in the United States and Europe.

Data quality matters; and it's worth noting that CoalSwarm, one of the organisations behind the new report, has data of undoubtedly better quality than bodies that might be more familiar. Whereas the International Energy Agency (IEA) models expected supply and demand, CoalSwarm simply counts plants, tracking every single one above a certain size as its status changes from planning to construction to completion - or, increasingly, to cancellation.

However, its overall conclusions are supported by the IEA, which reported last week that carbon emissions globally have been steady now for three years - the main reason being reduced coal-burning in China and the US.

China powers down

The reasons behind the tightening coal pipeline aren't hard to discern.

In China, urban air pollution is so bad that the government fears public unrest; and coal burning is the major culprit, unlike in most Western cities where traffic is the main pollutant. There's the over-capacity issue (in other words, supply exceeding demand).

There is the Paris Agreement. There is China's long-term development pathway, which calls for more sustainable growth and, in its power plan, a rollout of clean energy and a step-change in efficiency. There are its plans to be a global leader in clean technology.

India is, broadly, following the same trajectory, with a rickety grid adding to coal's problems.

Both countries also want to restrict the amount of coal they import; and in China's case, becoming a net exporter would be ideal. Yet both are also moving to close the least productive mines.

Reducing consumption is the only logical route to achieving all goals simultaneously.

There's a Trump angle to all this. Just today rumours are circulating about a planned White House Executive Order designed to boost the coal industry (by means that aren't yet clear).

But also today came news that two more US coal-fired power stations are about to burn their last. Increasingly, against both US and global trends and indeed against his own plans to boost natural gas output, the President appears to be channelling King Canute.

There's a Germany angle. For a nation that loves to proclaim its 'green' credentials - a boast that in many ways is justifiable - its reliance on coal-fired power stations is becoming an embarrassment. You cannot claim 'green' leadership while relying on coal (including lignite) for two-fifths of your electricity.

There's a UK angle. If current trends and current policy stay where they are now, the nation that commercialised coal-burning will quit the smoking habit within eight years. Theresa May's government, unlike that of her hand-holding friend across the Atlantic, is clearly swimming with the tide.

But most of all, there's a Paris angle.

Simply put, achieving the goals of the Paris climate agreement would be impossible if coal-burning was set to expand across the world - or even just in Asia. The maths of carbon budgets simply wouldn't allow it.

But a rapid turnaround in coal's fortunes, if it's maintained, moves the Paris targets from the "forget about it' bucket to the 'tough but achievable'.

So will it be maintained?

Well - new coal-fired power stations will be built. China, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Vietnam... all will add new plant to their existing rosters. Turkey, South Korea, Japan and several other nations may join them.

But the trends that brought coal around the corner aren't about to go into reverse. All coal plants within Beijing have closed - but air pollution in China's giant cities isn't over, nor in India's. Solar and wind power continue to get cheaper, and the restructuring of economies from Glasgow to Guangdong means demand in many countries is growing more slowly than anticipated, or is even falling.

China has frozen plans for hundreds of coal plants until at least 2020, including - for the first time - many that were already under construction. India plans to complete what's in the pipeline until 2022 (although currently, the completion rate is only one in six, so we should take 'planned' numbers with a pinch of salt) - but thereafter, as the National Electricity Plan currently stands, it may build no more at all, instead relying on solar, wind and nuclear power.

Is all of this news to governments and businesses? I would presume not: governments signed the Paris Agreement largely because their own research told them a low-carbon transition was no longer unaffordable, whereas unconstrained climate impacts were.

Today's report shows unequivocally that coal is the first casualty of the changing economics of energy and climate change. The fuel that once powered the world is burning ever more dimly.

Share