Australia - high impact, low ambition

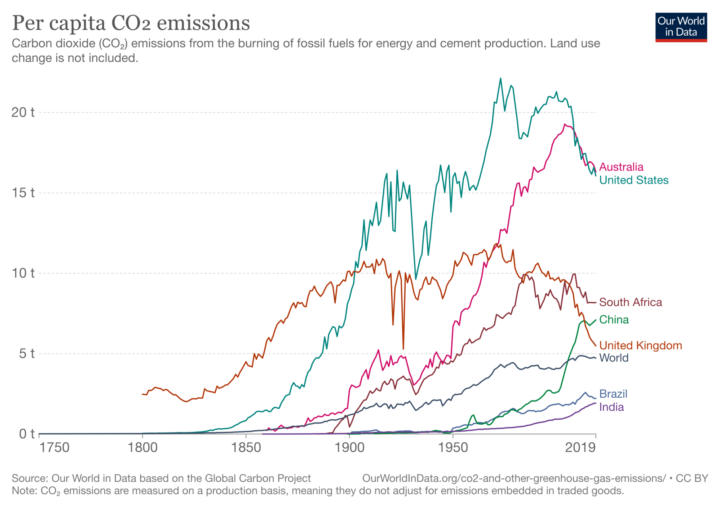

Australia is a wealthy, developed nation with one of the highest per-capita emissions in the world - and some of the weakest targets to cut them.

By Gareth Redmond-King

@gredmond76Share

Last updated:

Australia is a wealthy, developed country whose GDP ranked 13th amongst individual G20 nations in 2020. It also ranks 13th

on the chart of top greenhouse gas emitters worldwide – responsible for 1.3% of global annual emissions.

Australia has the smallest population of any individual G20 nation, at less than 26 million. Given the scale of its emissions, it therefore has one of the highest levels of per capita emissions: fourth in the world for greenhouse gases, and second only to Saudi Arabia for carbon dioxide emissions.

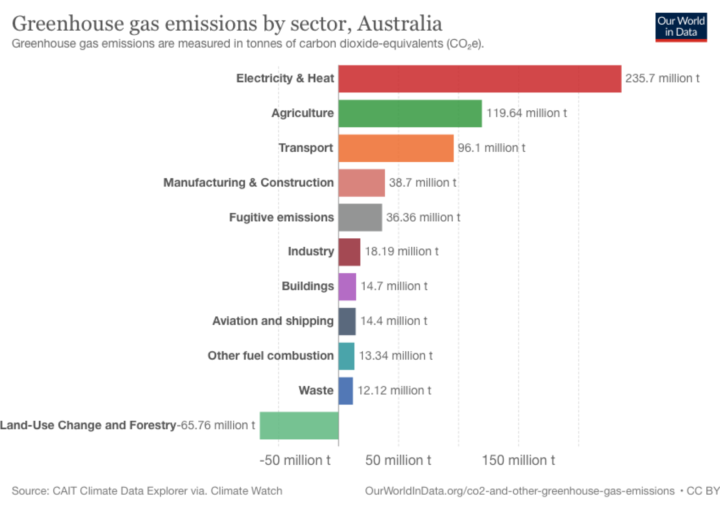

The biggest source of emissions in Australia is its power and heat sector – accounting for over 40% of greenhouse gas emissions. In 2020, more than half of Australia’s electricity was generated by coal, with a further 20% from gas – with just a quarter from renewable and other sources.

G20 emissions gap

As we explored recently in this briefing, G20 nations are crucial to closing the emissions gap ahead of COP26. They are responsible for nearly 80% of global emissions, yet only around half of those are yet covered by ambitious pledges to cut them in line with the Paris Agreement.

Australia does not have an ambitious pledge under the Paris Agreement, and was recently ranked last out of all the world’s nations for its climate action.

Inadequate emissions pledge

Climate Action Tracker (CAT) rate Australia’s national determined contribution (NDC) as highly insufficient, calculating it to be in line with a world warming by around 4°C. Not only has it not committed to an enhanced target for emissions reductions by 2030, Australia is also not on track to meet its existing target of a 26-28% cut on 2005 levels. Prime Minister, Scott Morrison has claimed to be on a path to net-zero, whilst Energy Minister Angus Taylor claims the country’s record is one that they can be proud of. However, it was only days before the COP26 climate summit before the Morrison government did finally commit to a target of net-zero by 2050. It still refuses to submit an updated short-term target, however, and asserts that net-zero can be achieved without serious reduction in fossil fuels.

Australia is also rated as critically insufficient for its approach to land-use and forestry, with Climate Action Tracker pointing out the remarkable fact that the country is “the world’s only developed country that is classified as a deforestation hotspot”.

Additionally, CAT classifies Australia as critically insufficient for their contribution to climate finance. This is backed by ODI’s assessment that Australia had, earlier this year, contributed less than a fifth of its ‘fair share’ of the $100bn a year support to developing nations promised by wealthy countries by 2020.

Why Australia’s emissions & action matter to the world

As well as heavy reliance on coal for power, Australia is also the world’s largest exporter of coal, and of liquefied natural gas (LNG) – meaning that their fossil fuel production supports reliance on these fuels elsewhere. Coal accounts for nearly half of all global emissions from energy.

Successive Australian governments have heavily backed their fossil fuel industry. In 2020/21, Australia’s governments at various levels reportedly provided AU$10.3 billion (£5.5 billion) of public money to subsidise fossil fuel use and production. And the Gillard government’s carbon tax was repealed by Tony Abbott when he became Prime Minister meaning that falls in carbon emissions that had been driven by the tax were then also reversed.

Australia is a wealthy, developed nation with exceptionally high emissions for its size of population and amongst the top 20 historic emitting nations. Reducing its reliance on extraction and exporting of fossil fuels would clearly aid global efforts to phase out coal – for which there is some support in Australia, with Sydney, Melbourne and Australian Capital Territory already signed up as members of the Powering Past Coal Alliance. Its wealth and level of development should mean it has scope for investing in the transition to renewables and decarbonising its economy at a similar rate to developed European nations.

Why cutting emissions matters to Australia

Globally, and for individual nations, the costs of not acting to cut emissions are higher than those of taking climate action while the economic benefits of climate action are forecast to outweigh the costs.

According to a 2018 analysis, a 4°C warming world (the level with which Australia’s targets are currently aligned) could see Australia losing $117bn a year in GDP through to the end of this century. A study by the accountants, Deloitte, calculated that the Great Barrier Reef is worth AU$6.4 billion a year and 64,000 jobs to the Australian economy. The IPCC 1.5° Special Report forecast that, at 1.5°C of warming, we risk losing around 70% of coral reefs globally, whilst at 2°C we face losing all of them. Australia’s emissions are currently contributing at a rate on track to extinguish this AU$56 billion asset to their economy.

At 1°C+ of warming now, Australia is facing devastating consequences – as the bushfires of 2019-20 demonstrated graphically. The Australian Academy of Science has assessed the threats at 3°C of warming, and found that increased heat stress, harsher droughts and declining river flows would have severe impacts on Australia’s already stressed food and agriculture systems. They also found that up to a quarter of a million homes in coastal regions would be threatened by sea level rises, and that increasing risk from extremes of weather will render one in 19 Australian homes uninsurable as soon as 2030. Another recent survey of impacts suggests property values could reduce by AU$611 billion by 2050.

Averting these risks, and protecting critical tourism and agriculture sectors, would require stronger targets and more urgent climate action from Australia. As of days before the UN climate summit in Glasgow, there is no sign yet of enhanced short-term emissions pledges from Australia. Prime Minister Scott Morrison has confirmed that he will attend. It remains to be seen whether he will feel that he ought to come with new targets and commitments to back up a 2050 net-zero goal.

Share