Energy sources (globally and UK)

Where are we now with reducing emissions from our energy sources and what can be done post-COP26?

By Jess Ralston

@jessralston2Share

Last updated:

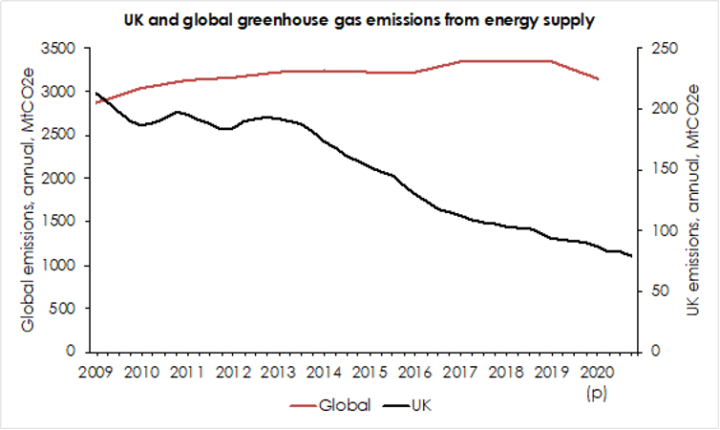

The world’s total CO2 emissions from energy reached 33.6 billion tonnes of CO2e in 2019, which is 64% higher than in 1990 and represents around two-thirds (68%) of the world’s total greenhouse gas emissions.1 In 2020, global emissions fell by 6% - the largest ever decline and five times more than the decline following the 2009 financial crash. In 2021, this is expected to rebound and emissions are predicted to increase by 5% as the economy recovers from the pandemic.

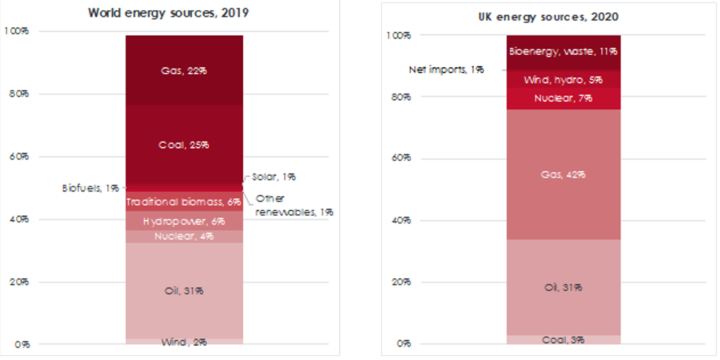

In 2021 the world is still reliant on fossil fuels for generating electricity, transport, industrial processes and heating buildings. Globally in 2019, 78% of energy used was from coal, oil or gas. Of these, coal is the most environmentally damaging with emissions of 0.32kgCO2e/kWh in the UK, however this will vary depending on the country due to the methods and sources of extraction, processing and transportation of the fuel.

Renewables such as wind, solar and hydropower have become much more commonplace in the global and UK energy systems over the last decade. For example in 2020, total renewable energy use increased by 3%, bucking the trend of other fuels which saw declines across the board. The primary driver was a 7% growth in electricity generation from renewable sources, meaning that now almost a third (29%) of all global electricity generation is from renewable sources. Of this growth in renewable electricity, wind is set for the largest increase (c. 17%), mainly driven by favourable policy in China and the US.

However, the International Energy Agency (IEA) has estimated that coal demand will increase by 60% more than all renewables combined in 2021, contributing to a predicted 5% rise in emissions in the next year. This is mainly due to coal being used extensively for heat and power and for industrial processes in Asia – with China alone projected to account for over 50% of global growth.

In the UK, electricity generated from coal has fallen from 40% a decade ago to just 2% in 2020. This is one of the quickest reductions in coal use for electricity in the world and the UK Government recently confirmed it will phase out all coal from electricity generation by 2024, placing it at the leading edge of ambition. Coal has largely been replaced by natural gas, which emits less carbon (0.2kgCo2e/kWh in the UK – again varying across countries), and renewables like wind and solar which made up 43% of electricity generation in 2020.

This means the UK’s emissions have reduced significantly more compared to the rest of the world. This places the UK at the forefront of decarbonisation, as it has reduced emissions by 44% while growing the economy 78% since 1990.

Where do we need to be?

In September 2021, the UNFCCC published an analysis of countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) – essentially climate targets set according to the Paris Agreement. They found that, whilst progress had been made, they still put the world on track for a catastrophic 2.7°C of warming – a considerable distance off the Paris Agreement target of keeping warming to 1.5°C. A key focus of COP26 will therefore be securing emissions reduction pledges to keep 1.5°C alive.

In the UK, emissions reductions are on target to reach the 3rd Carbon Budget – a Carbon Budget is a 5-year cap on emissions, set in advance according to advice from the Climate Change Committee – and the UK’s recent Net Zero Strategy means that it is now on track to meet the 4th, 5th and 6th Carbon Budgets from 2023 to 2037. Although the power sector has been relatively successfully decarbonised to date, by increasing the amount of renewables on the system and replacing coal with gas, sectors that are lagging far behind the pace of change required include buildings, transport and industry.

The UK Government’s recent Net Zero Strategy gives a good idea on how it plans to reach a net zero power system. For example, a funding model for a baseload (back up power topped up by other sources e.g. renewables) large scale nuclear power was announced in the Regulated Asset Base model – however this has faced criticism as it ties in consumers to paying for nuclear plants during the construction phase. On top of this, renewables mainly in the form of 40GW of offshore wind capacity by 2030 and 95GW by 2050 were also recently announced, which is likely to provide the bulk of the UK’s flexible energy system out to mid-century.

What would a successful COP look like?

The UK Government has set out its priorities for COP as coal, cars, cash and trees. This means that they will be seeking coalitions of nations working together to speed up phase out of petrol/diesel vehicles, to end deforestation, and ensure a rapid transition to clean energy that will help deliver on enhanced NDCs.

The UK will be pushing for other countries to commit to a solid phase out date for coal (mainly used for electricity generation), like the UK has set for 2024. The UK is joint founder (with Canada) of the Powering Past Coal Alliance, which aims to spur on action in this area and has been active since COP23 in 2017.

There has been some progress on the phase out of coal ahead of COP. Alongside the UK, some countries have committed to a completely clean electricity system by 2035 already, including Canada and the US. China, responsible for over 50% of coal use globally, has also committed to ending building coal plants abroad, but has yet to make any domestic pledges. Therefore promises to end coal use will likely be a key focus area for discussions before, and at COP26 in Glasgow.

However, the majority of countries have not set such a target, including many in Europe, and questions remain around commitments to phase out coal from the economy entirely – for example coal is a crucial part of the current way of making steel.

What does this mean for UK actionafter COP26?

While securing an international agreement to end the use of coal would be considered a success at COP26, domestic action following on from this will likely be a key area of scrutiny. In the recent Net Zero Strategy, the UK committed to all clean electricity by 2035, which was backed up with plans for a future energy system based on renewables with some nuclear power. Experts now agree that the strategy now needs to be backed by detailed policy and sufficient investment for it to be a success.

A strategy for improving the flexibility of the UK’s energy system as more renewables come online will be a focus of the coming decade, including plans for more battery storage, flexible sources like green hydrogen and reducing energy demand using energy efficiency in buildings and demand side response in industrial processes. These measures are designed to reduce costs of the transition and provide greater energy security and independence.