Brazil - leader turned laggard on climate

A former leader on climate action, host of the 1992 Rio Summit, Brazil is one of the G20 nations with weak climate targets ahead of COP26 - as well as home to one of the world's largest carbon sinks.

By Gareth Redmond-King

@gredmond76Share

Last updated:

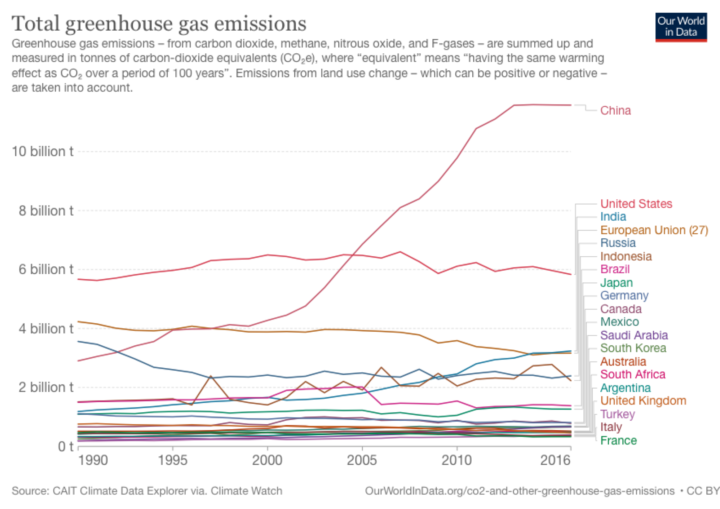

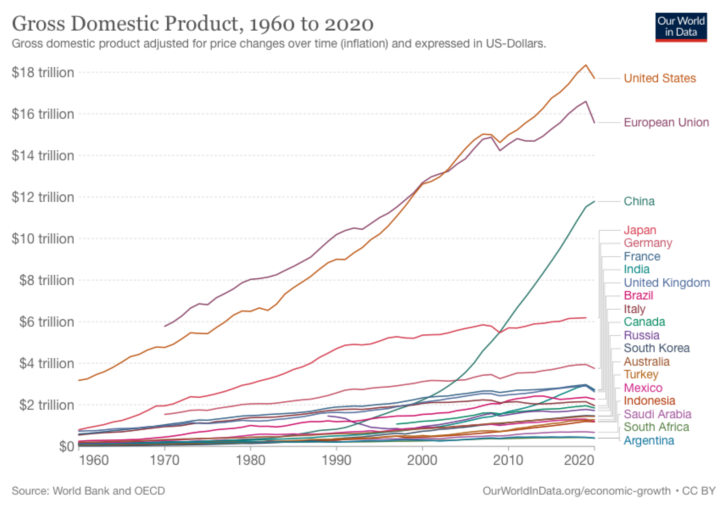

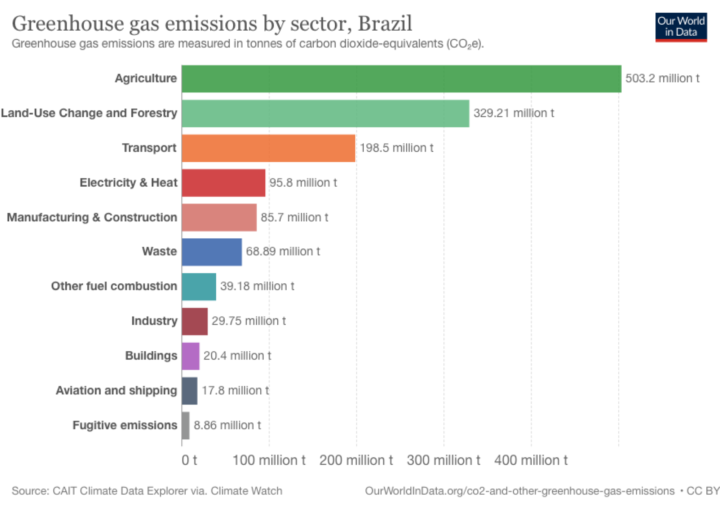

A developing country, Brazil is the largest economy in South America, a G20 member, and sixth biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, responsible for 2.2% of global emissions annually. The largest source of emissions in Brazil is agriculture and land-use, and it is home to 60% of the Amazon tropical rainforest – of critical importance for people, nature, climate systems and carbon storage.

Its emissions pledges are not aligned to the Paris Agreement goal of keeping warming to 1.5°C and have recently got worse, rather than more ambitious; not improving in the pledge submitted at COP26 in Glasgow. Brazil’s food production is jeopardised by projected temperature rises, but it stands to benefit economically from taking climate action – including GDP, jobs, agricultural productivity and human health.

Brazil is the largest economy in South America and, by GDP, eighth largest amongst individual G20 nations. However, it is also a developing country – classified by the UN as an ‘emerging upper-middle income economy’. Brazil is the sixth biggest emitter of greenhouse gases globally amongst individual G20 nations.

It drops to 17th when emissions per capita are measured – emissions per head of population. And is 16th in terms of biggest cumulative emissions – most of those further up the list being historic emitters: those countries which have emitted for longest.

Its current leader, Jair Bolsonaro, claims to have a strong environmental record. But evidence and testimony show that his presidency has rolled back several years of progress in tackling deforestation prior to his election in 2019.

G20 emissions gap

As we explored recently in this briefing, G20 nations are crucial to closing the emissions gap ahead of COP26. They are responsible for nearly 80% of global emissions, yet only around half of those are yet covered by ambitious pledges to cut them in line with the Paris Agreement. One of the nations that has not enhanced its climate ambition is Brazil.

Inadequate emissions pledge

Climate Action Tracker rate Brazil’s nationally determined contribution (NDC – their emissions pledge under the Paris Agreement) as highly insufficient.

Brazil did submit an ‘updated’ NDC in December 2020; however, it did not enhance ambition. In fact, according to Climate Action Tracker (CAT), their NDC “effectively weakens its already insufficient climate action targets for 2025 and 2030”. The actual targets for those years – 37% and 43% reductions respectively – remain the same. However, the emissions level for the baseline year of 2005 is now higher, which means that Brazil can increase emissions this decade, and still meet already weak targets.

Emissions in 2030 could, on the basis of that target, be 26% higher than when Brazil ratified the Paris Agreement in 2016. That would be in line, say CAT, with a world warmed by 4°C; Brazil’s existing policies are slightly better, but still in line with a catastrophic 3°C of warming.

Brazil has since submitted another updated NDC, at the UN climate summit in Glasgow. This, however, has failed to put Brazil on track for Paris goals putting them, at best, back where they were with their 2015 NDC.

Brazil’s NDC makes a provisional commitment to ‘climate neutrality’ by 2060 – also suggesting that it could bring that date forward in certain circumstances.

One of the areas in which Brazil has made progress is in deployment of renewables; according to Brazil’s National Energy Balance 48% of its energy comes from renewables. However, much of this is from hydropower which can involve flooding of large areas and be environmentally destructive in its construction.

The biggest problem

Nearly two thirds of Brazil’s emissions come from agriculture, and from land-use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF). In Brazil’s case, those ‘LULUCF’ emissions are essentially from deforestation, and are rising as deforestation increases. Earlier in 2021, it was reported that parts of the Amazon are now emitting more carbon than they absorb.

Brazil’s far-right President, Jair Bolsonaro, has claimed deforestation in August 2021 was lower than the same month the previous year. According to some systems this could be true, but the 2021 deforestation is still significantly up on previous years, including 2018. In August this year deforestation in the Cerrado region was 137% higher than August 2020.

Bolsonaro was elected on a manifesto that included rolling back ‘suffocating’ environmental protections, and opening up the Amazon to further agribusiness exploitation. Unsurprisingly, therefore, his country’s NDC fails to include targets from the previous NDC to stop illegal deforestation and restore forests.

At US President Biden’s April climate leaders’ summit, Bolsonaro pledged to double-funding for environmental protection, as his government called for $1bn a year in foreign aid to support this. That budget was reportedly cut the very next day.

Many countries that import products from Brazil, including the UK, are introducing laws to tackle deforestation to which they are linked. In the UK, companies have called for this law to be tightened to cover all deforestation, not just that deemed illegal in the country where it occurs. For a country like Brazil, under the current regime, illegality is a low bar.

Why Brazil’s emissions & action matter to the world

At 2.2% of global annual emissions, and sixth biggest emitting nation, Brazil’s contribution to cutting greenhouse gases is important. Around 48% of global emissions come from nations whose global annual share is 3% or less.

But 60% of the Amazon tropical rainforest is in Brazil, and the Amazon is globally important. It is home to 30m people, 20% of the planet’s freshwater, 10% of the planet’s known wildlife species, and a third of all known terrestrial plant, animal and insect species. As well as storing tens of billions of tons of carbon, the Amazon helps regulate rainfall and therefore the wet and dry seasons on the South American continent.

However, we are losing forests globally at the rate of an area the size of the UK, every year. In the Amazon, as in many other parts of the world, trees are felled to make way for livestock and food for livestock, and to feed the global timber industry. This means that deforestation is part of the supply chains of the goods and services we consume all over the world – none more so than our global food system.

The Amazon has also, in recent years, experienced worsening fires, also the cause of harm to forests in other parts of the world experiencing intensifying and more frequent wildfires, such as the Pacific Northwest over summer 2021.

The scale of carbon stored in forests, as well as the many other economic benefits provided by forests like the Amazon, is why the UK, as hosts of COP26, have made curtailing deforestation one of the priorities of their presidency.

Why cutting emissions matters to Brazil

Brazil is no more immune to the impacts of climate change than any other nation on the planet. Temperatures in Brazil are projected to rise by between 1°C and 2.2°C by 2060, with some models predicting up to 3°C by 2050.

The Paris Agreement seeks to keep warming to 1.5°C. We know that even the 1°C of warming experienced globally over the last century is not ‘safe’; but the IPCC special report on 1.5°C in 2018 demonstrated how much more dangerous impacts become above 1.5°C.

An IPCC report in 2014, suggested that temperature rises in Central and South America would lead to a reduction in NE Brazil’s rainfall of over a fifth by the end of the century, with impacts over the next decade jeopardising food production and risking food security for Brazil’s poorest communities. A 2018 study calculated that the country’s maize production would fall by 8% with 2°C of warming – and by 19% with 4°C of warming. The IPCC projected a bleak future for some plant and bird populations in Brazil too, as groups would be dislocated southwards, where fewer natural habitats would sustain them.

These impacts have economic costs. A 2018 assessment projects GDP reductions on today of nearly 2% in a 2°C warming world – intensifying to cuts three and a half times that in a 4°C warming world: -6.8%.

By contrast, analysis by the World Resource Institute and New Climate Economy suggests a low-carbon recovery from covid – one that involves cutting emissions and halting deforestation – would have huge economic benefits for Brazil. A GDP boost of $535 billion and 2 million more jobs would be accompanied by health benefits from reduced air and water pollution, greater food security, and an additional $3.7 billion of agricultural production.

What is more, reversing their approach to deforestation would re-open doors to international investment and finance. According to the WRI/New Climate Economy study, investors with trillions of dollars of assets have threatened to, or are already withdrawing from investments with deforestation risk. And global supermarket brands have recently threatened to withdraw from Brazil for the same reason.

Past leadership

Brazil hosted the first UN climate summit, in Rio in 1992, at which the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was born. From the UNFCCC came the meetings known as the conferences of the parties (COPs) – of which Paris in 2015 was the 21st, and Glasgow, in November, represents the 26th.

From 2004 to the early 2010s, Brazil made huge efforts to slow deforestation, its greenhouse gas emissions fell by a third from 2004 to 2011, and in 2015 at COP21 in Paris, it joined the High Ambition Coalition. But since Bolsonaro’s election, Brazilian Ministers and negotiators have not only been far from efforts to secure high climate ambition, they have actually blocked progress on some aspects of negotiations.

Whilst COP26 is unlikely to see Brazil return to its past leadership role, the commitment on net-zero in April, and a new tone around deforestation (albeit not borne out by action) at least suggest that Jair Bolsonaro and his administration feel some international pressure to act on climate.

With all the insight, analysis, and data on the road to the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow in November 2021.

Share