Net zero: aviation and shipping

What progress is being made in reducing aviation and shipping emissions?

By George Smeeton

@@GSmeetonShare

Last updated:

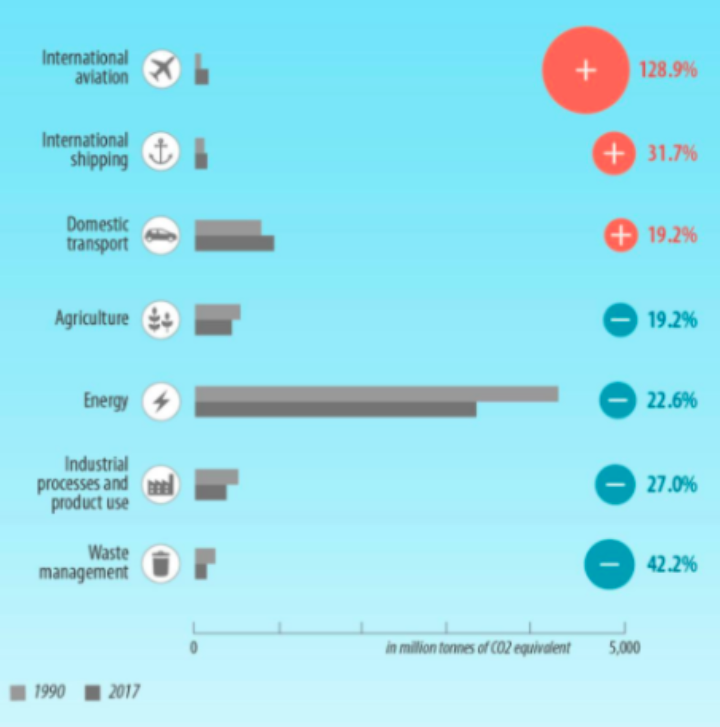

Although it is difficult to measure and allocate emissions from these methods of transport, it is thought that aviation and shipping account for around a tenth of the UK’s emissions. In the EU, together they account for about 7% of total emissions. This represents a more than doubling of emissions over the past two decades.

Aviation in the UK

In 2018, aviation accounted for 7% of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions, a rise of 88% since 1990 in contrast to rapid declines in other sectors. As other sectors like energy generation and industry decarbonise more quickly, aviation has stayed around this level since 2008, and predictions are that it could account for 23MtCO2e of emissions in 2050, which will need to be balanced by greenhouse gas removals.

For the first time, the 6th Carbon Budget covers international aviation as well as shipping. The Climate Change Committee (CCC) suggest that to reach the 6th Carbon Budget target in the most likely ‘Balanced Pathway’ scenario, growth in demand for international flights must be limited to 25% with no net expansion of UK airport capacity, efficiency must improve and alternative fuels like biofuels and synthetic must become the norm.

Decarbonising flight

The aviation industry and other experts argue that while a small number of flights can currently be decarbonised for the purposes of demonstration or for very short journeys, prospects for decarbonising flight overall in the medium term are currently very slim.

Improving the design of planes' wings, fuselage and engines can reduce the amount of fuel burned, as can better management of traffic to reduce flight times. It may also be possible to use jet streams more effectively to limit fuel use and decrease flight times.

Biofuels are proven to be technically feasible through blending them with kerosene. The challenge is to reduce their costs through greater uptake and ensure that they are truly low-carbon and do not compete with land for food crops. A consortium of aviation industry players are developing green fuels made from waste in the UK, but recently oil and gas incumbent Shell pulled out, favouring a similar scheme in Canada instead.

Short-haul commercial electric flights may be possible as batteries become more efficient over the coming decades, though the timeframe for this is uncertain. Norway aims for all short-haul flights to be 100% electric by 2040. Airbus, Boeing and NASA are among organisations developing electric planes.

Hydrogen-powered flight is another avenue of research with Airbus running the ZEROe programme that targets green hydrogen (made from renewable electricity) as a fuel for ‘zero-emission commercial aircraft’ by 2035. Another UK-based consortium has received funding from the Government’s Future Flight programme and will examine the potential for a larger, 19-seater, 500-mile range aircraft to run on hydrogen.

In Britain, the Government’s recently launched ‘Jet Zero’ council aims for Britain to deliver the world’s first zero emission long haul flight by 2050. In the shorter term, it has announced £15 million support for sustainable aviation fuels and another £15 million for FlyZero in the Energy White Paper and in addition is supporting advanced fuels under the Future Fuels for Flight and Freight Competition. Ministers also recently announced £343 million Government and industry investment for research and development of electric aircraft and hybrid-electric propulsion systems.

Negative emissions and flying less

The more flights increase, the more 'negative emissions' will be required to cancel them out. As it looks very unlikely that aviation will be able to decarbonise completely, experts think that it ‘stands out as an obvious sector that could require removals to offset its emissions’.

Flying less would also help reduce emissions and, with 70% of all flights in Britain being taken by just 15% of adults, the evidence suggests this would not be a widespread inconvenience. Only 10% of airport passengers are people living in Britain doing business abroad so reducing the number of flights for holidays is one option.

The CCC has said that given the limits of cuts achievable by other sectors, aviation emissions should be no higher than 37.5 Mt in 2050, equivalent to their level in 2005 and representing about a quarter of the total allowable UK emissions by 2050. The balanced pathway as part of the 6th Carbon Budget sees passenger numbers increased by around 25% and residual emissions from the sector to be 23MtCO2e in 2050.

In February 2020, a third runway at Heathrow was ruled illegal over climate change concerns and its ability to jeopardise the Government’s net zero target. However, in December 2020 the Supreme Court overturned this decision. This being said, there are still major obstacles before construction can begin, such as a public enquiry and planning inspectors’ approval. The Government is expected to publish a new Transport Decarbonisation Strategy, covering aviation, in 2021.

Shipping

Shipping has long been placed in the 'hard to abate' category. But technological developments in the last few years have enabled 'net zero' emissions from the maritime sector to become a politically possible goal, with many countries calling for it and taking action towards it.

Shipping is responsible for 3% of the UK’s emissions, down by around a fifth since 1990 as emissions have been falling slowly over the past two decades. As shipping is now included in the UK’s 6th Carbon Budget, there will likely need to be improvements to vessel efficiency and use of zero carbon fuels such as ammonia (made from low carbon hydrogen) if the shipping sector is to reduce its emissions substantially by 2050.

Battery electric propulsion systems in the maritime sector are evolving rapidly, and are being deployed in the inland, coastal and ferry transport sectors.

Alternative fuels such as biofuels and hydrogen are also being developed, with one study showing that 99% vessels in 2015 could have been powered by clean hydrogen,; in December 2019. the world’s first liquefied hydrogen carrier ship was launched in December 2019.

International progress

Shipping and aviation were excluded from the Paris Agreement’s national accounting due to the difficulties of attributing emissions from complex international supply chains to individual countries. This means they often do not form part of each country’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), or pledges on climate.

Instead, responsibility for dealing with shipping sector emissions has been delegated to a specialist UN agency – the International Maritime Organisation (IMO).

While progress at the IMO has been slow, in the last few years many countries have adopted a net zero target.

Going into the IMO negotiations in April 2018 in London, EU member states agreed a common position of supporting a 70-100% reduction in shipping’s greenhouse gas emissions worldwide by 2050, compared with 2008 levels.

Ultimately the wording that came out of the IMO negotiations was 'at least' a 50% reduction by 2050, while 'pursuing efforts towards phasing them out entirely' on a trajectory consistent with the Paris Agreement.

The political will to put an earlier time-stamp on net zero for international shipping remains strong, driven by Pacific Island states and EU countries including the UK.

Technological solutions

Is this achievable? Yes, according to the OECD’s International Transport Forum, which found that zero-carbon shipping is possible by 2035 based on current technology. Maersk, the largest container ship and supply vessel operator in the world agrees, with a recent commitment to reach carbon neutrality by 2050. To achieve this goal, carbon neutral vessels must be commercially viable by 2030.

Zero-emission vessels already exist – the problem is one of scaling up from the predominantly inland and coastal routes which they currently ply to the vast ocean-going vessels that carry 80% of global trade.

At present ferries, of both the tourist-carrying and Roll-On Roll-Off (RORO) car-carrying variety, are at the forefront of maritime electrification. The Indian state of Kerala hosts Asia’s first solar-electric ferry - the 'Aditya' - which has been in commercial operation since 2017 and is the first of 10 such vessels. Its introduction was driven as much by concerns over air pollution as climate change.

Norway has operated an electric ferry for commercial purposes since 2015, expanding to cover the whole of its fleet by 2023. In 2021 the UK’s first electric ferry will start carrying passengers after a series of trials in 2020.

In 2019 the Norwegian Parliament decided that the Norwegian fjords – visiting cruise ships - would be a 'zero emission zone' from 2026. Viking Cruises is developing a 900-passenger zero-emission hydrogen cruise ship, building on the successes of trial vessels in Belgium and Finland (an Arctic research vessel).

The world’s first commercial car-carrying ferry powered solely by renewable hydrogen is being built in Scotland, for delivery in 2020 and use in the Orkneys. (The UK has been an early supporter of maritime hydrogen: a smaller scale zero-emission hydrogen vessel journeyed around the Isle of Wight in 2016.)

Freight shipping

Turning to larger vessels, a Chinese company lays claim to have built the world’s first battery electric cargo ship (ironically, to carry coal), while the first battery electric and autonomous container ship, the YARA Birkeland, is being built in Norway.

Reducing emissions by cutting fuel consumption can save a shipping company millions of dollars a year. For this reason, Maersk, the world’s largest shipping company, fitted its first wind-propulsion Flettner rotors to two of its tankers this year, with plans to expand across the fleet if the trials are successful.

While wind-assisted technology will likely expand in a cost-saving peripheral role, the tight schedules of container shipping will ultimately require zero-emission renewable fuels to fully decarbonise. It is here that further research, funding, and collaboration to scale up is needed to bring lab and trial versions to the mass market.

The shipping industry currently spends well over $100 billion a year on its fuel bill. This market is the prize for innovators once the price of renewable energy falls into a comparable range as its fossil-fuel competitors, perhaps helped by the tougher sulphur emission standards coming into force globally in 2020, and at some point, a carbon price.