Around the UK

What are the administrations in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland doing to curb emissions?

By Richard Black

@_richardblackShare

Last updated:

Across the administrations

Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland accounted for 9.3%, 7.6% and 4.2% of total UK emissions, respectively in 2017. Scotland has seen the steepest emissions reductions by some way (47%) since 1990, as a result of a shift to renewables in the power sector and closure of coal power stations. Emissions in Wales have fallen by 25%, but in Northern Ireland emissions have only fallen by 17%, around a third of that in Scotland.

Regarding emissions sources, agriculture and forestry have a bigger role in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland than in the UK as a whole; these emissions are relatively hard to measure accurately.

Wales is the most industrial country, with the greatest role for power plants, refineries and iron and steelworks, while Northern Ireland has the least heavy industry.

In terms of efforts to fight climate change, there are some limits on the responsibilities of the three administrations.

They have no powers to regulate energy, including power generation, meaning that UK-wide low-carbon energy support schemes apply.

All three countries have responsibility for economic development and the environment, however, and each has set targets to cut emissions and develop renewable power. And they all use some of their own finances to boost home energy efficiency.

Scotland

Scotland has particularly rich renewable energy resources, which it estimates at a quarter of all Europe’s tidal, wave and offshore wind potential. And it has a large carbon sink as a result of extensive forests, contributing more than half of the UK’s total carbon sink.

The Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 came into force a year after the Westminster equivalent and, following the CCC’s recommendation in 2019, was amended in the Climate Change Bill.

It sets a long-term target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 100% in 2050 relative to 1990 (identical to the UK target) and established the principle of five-year carbon budgets. Unlike the Westminster government, Scotland also has annual targets.

Scotland has an interim reduction target of 42% by 2020, which is more ambitious than the UK-wide 34%. So far, it has set emission reduction targets of 70% by 2030 and 90% by 2040.

However, it has repeatedly missed the annual targets. The reasons for this vary, but in 2017, emissions from transport, business, industry and waste management increased slightly so that the target was exceeded by about 6%. This being said, it is widely recognised that Scotland’s long-term targets are ‘very challenging’.

Part of this difficulty reflects changes in how emissions are measured, and the progress that is yet to be made in decarbonising buildings, transport, and agriculture and land use.

The Scottish Government is more upbeat. It highlights that there has been much progress; in 2017 domestic emissions targets were met and the country was just 3% away from the 2020 target being hit. This indicates that they still are on course.

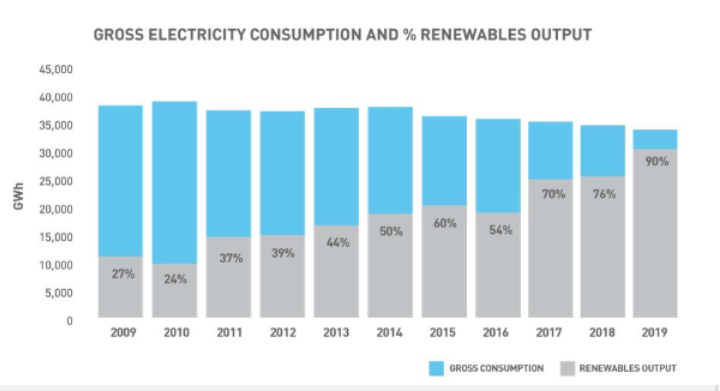

Scotland had a target to generate renewable power equivalent to the country’s entire electricity consumption by 2020, with an interim target for 50% of consumption by 2015.

The 50% target was met easily, with 60% renewables in 2015 and they look set to do it again for the 2020 target as a record 90% of electricity consumption was from renewables last year.

However, the Scottish Government's programme for 2020/21 seems to address this; nearly £1.6 billion to transform buildings has been promised, including renewable heating. They expect that under new policies, installations for renewable heat will grow from just 2,000 installations per year in 2020 to 64,000 homes fitted in 2025 – a cumulative total of around 126,000 homes.

That's equal to 5% of Scotland's housing stock retrofitted with low carbon heating by 2025.

However, more remains to be done on low carbon heating. Despite setting a target of 11% of heat (non-electrical) to come from renewables by 2020, by 2018 they were just over halfway there.

Wales

The Welsh Government accepted the CCC’s target for 95% emissions reduction by 2050 and has said “it wishes to go further than its new target of 95% emissions reductions and aspires to reach net-zero by 2050”. This means that there will be legislation for 95% emissions reduction, but that net zero is just an ambition.

However, the Welsh Climate Change, Environment and Rural Affairs Committee are keen to note that they believe around 60% of their emissions are from non-devolved policy areas, such as energy supply, and so they have limited control over what they can achieve without help from the UK Government.

Wales has an aspirational target to develop 22.5 gigawatts of renewable power by 2025, compared with just 1.8 GW in 2013. It is well off track.

The Committee on Climate Change has made four main recommendations for Wales:

- develop a low-carbon heating strategy

- cut heavy industry emissions

- increase adoption of electric vehicles

- meet existing tree-planting targets

Northern Ireland

Unlike Scotland and Wales, Northern Ireland has no legislated greenhouse gas emission reduction targets and the CCC has said it is at risk of falling behind the rest of the UK. Although, it has set a target of reducing emissions by 35% on 1990 levels by 2025 under its Greenhouse Gas Action Plan.

That is rather less ambitious than the equivalent UK-wide target of a 50% cut. The lower ambition reflects the greater share of agriculture in Northern Ireland, a sector where emissions cuts are more difficult.

In 2017, Northern Ireland’s emissions were just 17% lower than 1990 levels, compared with 40% lower across the UK as a whole. Emissions have fallen just 1% since 2013.

However, it reached its targets of generating renewable power equivalent to 20%of total electricity consumption in 2015, and exceeded its 40% goal for 2020 in June 2019.

The CCC has recommended that “actions to address climate change must be taken as soon as possible across all sectors of the economy” and suggested that the following three actions would put Northern Ireland back on track for both its emissions and renewable energy targets:

- develop networks and renewable energy in heating

- improve monitoring of agricultural emissions

- boost electric vehicle uptake.

The Committee has advised Northern Ireland to establish its own Climate Change Act, as in Scotland and in the UK as a whole.