Renewable Energy in the UK

The costs of renewable energy, including ‘back-up’ power, are often discussed in media and political circles. This briefing brings together information on renewable energy, costs, and policies.

By George Smeeton

@@GSmeetonShare

Last updated:

Renewable energy now accounts for just under half (45%) of the UK’s power generation, more than gas which accounted for just over a quarter of generation (28%). The costs of renewable energy, including ‘back-up’ power, are often discussed in media and political circles. This briefing brings together information on renewable energy, costs, and policies.

Key points…

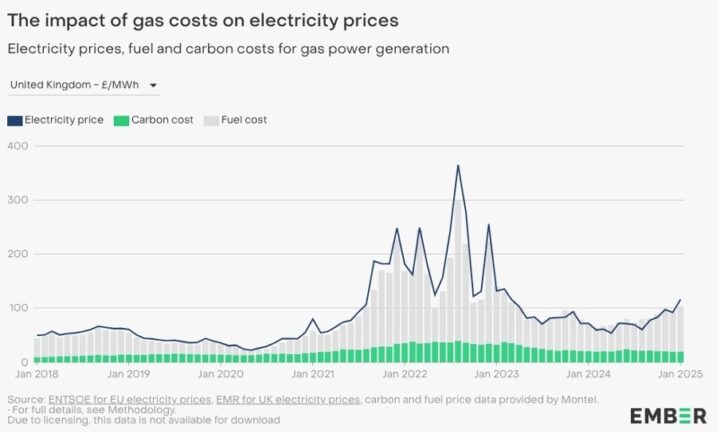

- Gas power stations currently set the UK electricity price 97% of the time, according to Nesta, which is why power prices shot up during the gas crisis.

- The Contracts for Difference (CfD) scheme offers fixed prices for renewable electricity generation, which help to limit electricity price increases when expensive gas is pushing up the costs of wholesale electricity. With more renewables on the power system experts such as Cornwall Insight and the Energy Transitions Commission agree the price of electricity should be lower than it would otherwise be.

- The costs of providing back-up power for when demand could exceed supply accounted for just 6% of current household electricity bills in 2024. The reduction in wholesale electricity prices from renewables are expected to more than offset any increase in these balancing costs according to the National Energy System Operator (NESO)..

- There are a number of tools available to the NESO, which they have frequently used over decades, to balance the grid and ensure security of supply. The NESO is “confident” it can continue to manage the transition to a clean power grid without blackouts.

How does renewable energy impact electricity prices?

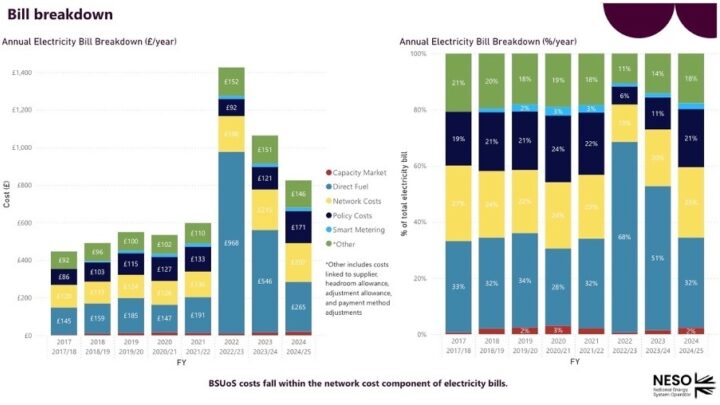

- The single largest component of household electricity bills is the wholesale electricity price. In 2024, the wholesale price made up 32% of the typical annual household electricity bill, but in 2022 during the peak of the gas crisis, this was higher at 68%.

- The UK uses a “marginal cost pricing system” to determine the wholesale electricity price, which means that the wholesale price reflects the running cost of the most expensive power plant needed to meet demand – this is usually gas.

- Electricity generators will bid for the minimum price they are willing to accept to generate electricity. The bids are accepted in ‘merit order’ until there is enough generation to meet demand; the cheapest first (increasingly renewables), and the most expensive last (usually gas). However, the price of all units of electricity is set according to the bid price of the most expensive unit needed to meet projected demand: this is the ‘marginal cost’.

- Gas-fired power plants are much more expensive to run than renewable power plants, due to their high fuel costs, which is currently the case. Research shows that in the UK, gas sets the price for all electricity 97% of the time. This is the highest proportion of any EU country and largely explains why electricity prices rise when gas prices do. Before gas prices were increased in the crisis, gas plants with lower efficiency set the price as they were the most expensive, due to requiring a higher gas demand per unit of electricity generation.

- Wholesale electricity prices are forecast to fall as renewable power generation capacity increases, e.g. by Cornwall Insight. Real-world examples also make clear the impact on displacing gas-fired power generation with renewables: wholesale electricity prices in Spain – where renewables provide more power than gas – are much lower than prices in Italy, where gas provides more power than renewables.

What are the “back-up” costs of renewable energy?

- The UK currently relies mainly on gas-fired power plants to “back up” its renewable electricity generation. These plants are generally switched on only during periods of high (or “peak”) electricity demand and are known as “peaking plants” or “peakers”.

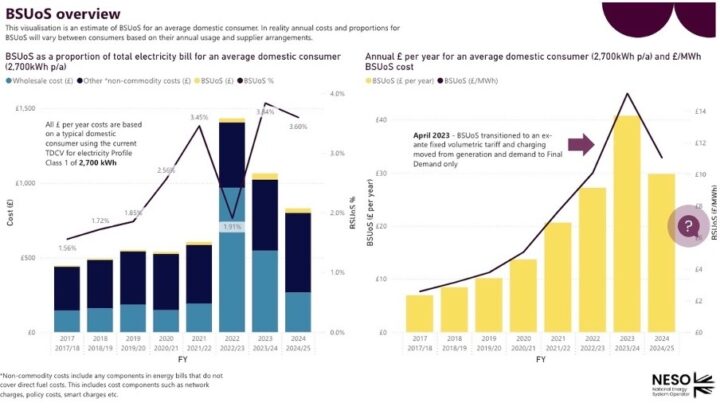

- The costs of running peaking power plants to "back up" renewable power generation are priced into UK household electricity bills through balancing (or "BSUoS") costs and Capacity Market (CM) costs. Together, these costs accounted for just under 6% of a typical household electricity bill in 2024, data from the National Energy System Operator show, many times less than the wholesale costs. BSUoS costs are not new, as there have always been a need for balancing services, including pre-renewables.

- While it is true that balancing and CM costs, which are newer, will increase as renewable power generation capacity rises, it is unlikely that increases to these minor components of electricity bills would outweigh the reductions in wholesale prices, which account for a much larger share of bills.

- Industry projections indicate that the more renewable power generation capacity the UK has, the lower the total costs.

Does more renewable energy mean higher electricity prices?

- No. The UK’s electricity price is overwhelmingly determined by the cost of gas power generation.

- Also, examining price data from the heights of the energy crisis in 2022-23 reveals that, rather than fuelling the increases in electricity prices, domestic renewable power generation shielded UK consumers from further price rises.

- When gas prices spiked, the corresponding spikes in electricity prices were smaller, as we were not entirely dependent on gas-fired power plants to meet demand.

Renewables therefore act as a price stabilisation mechanism by reducing the amount of time that gas sets the price for all electricity generation. As the rollout of renewables continues, gas will set the price for all generation less, and this will result in more stable bills for households as the volatility in the gas markets will not filter through as much.

What are the subsidies for renewables?

- The primary Government incentive for the development of renewables is the Contracts for Difference (CfD) scheme, through which developers receive a fixed price for their power generation, which helps them recoup initial investment costs. Essentially, generators with CfDs receive a subsidy when the wholesale electricity price is low, but pay back consumers when the electricity price is high. This de-risks the investment and so reduces financing costs and hence costs for customers, and has been successful in securing the roll out of offshore wind, in which the UK is the second-largest market in the world, behind China.

- Contracts for Difference (CfDs) are financial contracts between developers of renewable power plants and the Low Carbon Contracts Company, on behalf of the Government. However, the Government sets the budget for the CfD auction rounds, and has been criticised for using outdated “reference prices” for gas, which make the budget artificially smaller and limit the number of renewable projects that can secure a CfD.

- Despite being called a budget by the Government, which was set at a record £1.5bn in 2024, it is highly unlikely that this amount of money will ever be awarded to CfD recipients. This is because wholesale electricity and strike prices under CfDs are expected to remain broadly similar into the future. Therefore, any repayments in either direction (to generators or bill payers) is likely to be limited.

- In the auction process, renewables developers bid for the minimum fixed price (in £ per Mega-Watt hour) they require for the project’s electricity to enable them to recoup their investment costs over the course of the contract. The lowest bids receive CfDs, and the final fixed prices are known as the strike prices.

- Electricity generators with CfDs only receive payments “when the market price for electricity generated … is below the Strike Price set out in the contract”. These payments are recouped from electricity suppliers via consumers’ energy bills.

- As the subsidies or repayments depend on the wholesale electricity price, which is set by gas, projections can be made about the costs of CfDs but they often change. However, the Government has stated that during the gas crisis, when wholesale gas prices were high, CfDs reduced the average household bill by £18.

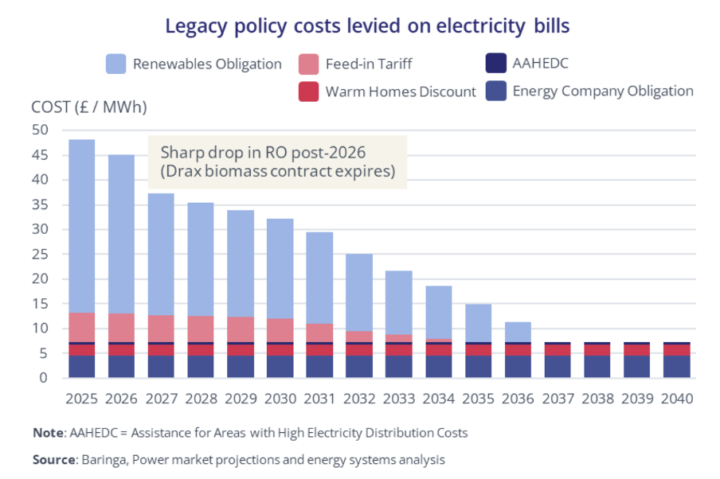

- Older subsidy schemes like the Renewables Obligation (RO) historically cost more than CfDs, because they funded renewables when they were more expensive to build. The RO worked to lower costs, for example the cost of developing and running an offshore wind plant over the course of its lifetime is around 50% less in 2020 than it was in 2010. However, RO contracts are now expiring and subsidies for this scheme peaked in 2024 and 2025 and will fall thereafter.

Why does the US have cheaper energy than the UK?

- US electricity prices also depend on gas prices. US gas prices have not risen in line with UK prices because they are less vulnerable to volatility on international markets as the US is not reliant on imports, as the UK and the EU are, and because US has had limited export capacity until recently, and so was partly insulated from gas prices in other markets (mostly Europe and Asia). However, US gas prices do respond to international factors to a degree, including during the gas crisis.

- The UK currently meets around 50% of its total gas demand with domestic production. It is implausible that this could increase to 100% to match the US, because the North Sea is a naturally declining basin and production is projected to fall over time, regardless of new drilling.

- For example, the North Sea Transition Authority’s projections show that North Sea gas production will continue to decline whether or not new drilling takes place, falling by 53% in existing fields by 2030, compared to 51% if all new fields and potential future discoveries came into production. There will be similar differences in production levels in 2050 whether there is new drilling or not: from 97% down to 95%. This means that the most effective way to reduce rising imports would be for the UK to start to reduce demand for gas, for example by building out renewables and transitioning away from gas boilers.

- Fracking in the UK would not have the same impact as in the US, again because prices in the UK depend on international markets, but also because the UK’s geology is fundamentally different to the US’. For example, the UK’s shale reserves are split into smaller pockets that would be harder to access – and of those reserves that could be accessible, three quarters would have to be left alone to avoid disrupting homes and infrastructure.

Do we need to upgrade the UK’s electricity grid?

- In a business-as-usual scenario, some grid infrastructure such as pylons would need to be upgraded anyway. However, bringing more sources of power online and more technologies such as battery storage facilities to manage the grid will require more connections, more transmission cables (e.g. pylons) and more distribution network infrastructure (e.g. transformers) to bring the power into households at a suitable voltage.

- At present, electricity transmission networks cost several tens of pounds on the typical household bill. Investments in onshore transmission infrastructure are recouped from customers (households, businesses, etc) over 45 years. If a company invests £1bn in a year on new onshore infrastructure, then that investment, coupled with the costs of finance, operations and maintenance, translates into a household cost averaging around 50p per year, ECIU estimates show based on industry information.

- Generally, underground cables are up to 10x more expensive to build than overhead lines with pylons, and around 5x more expensive over their lifetime including operational and maintenance costs (see reports by Parson-Brinkerhoff and National Grid). Figures for the current example of the proposed Norwich-Tilbury line in East Anglia are in these expected ranges (see options report), with costs for underground options compared to an overhead line being 6.5-9x for capital costs and 6x for lifetime costs.

- There have been several Government studies on a “community benefits” scheme that might incentivise households to have grid infrastructure like pylons in their local area. Electricity bill discounts were identified as the type of community benefit that was able to help increase acceptance for new transmission infrastructure (78%). This was followed by jobs, training and apprenticeship opportunities for local residents (65%) and direct payments to those in close proximity to the new transmission infrastructure (63%).

- Government research also suggests that around half (49%) of respondents would find new transmission infrastructure acceptable, while around a third (32%) would find it unacceptable. Around 3 in 4 found underground cables more acceptable than overhead lattice pylons, and around half (51%) found new overground T-pylons to be more acceptable than overground lattice pylons. However, once made aware of the environmental impacts of underground cables, such as greater loss of trees, shrubs, and hedgerows, these levels of support for were not sustained.

This briefing, Renewable Energy in the UK, is available to download here.

Share