Levelling up or letting down?

Tackling poor quality homes in marginal constituencies could swing election success

Last updated:

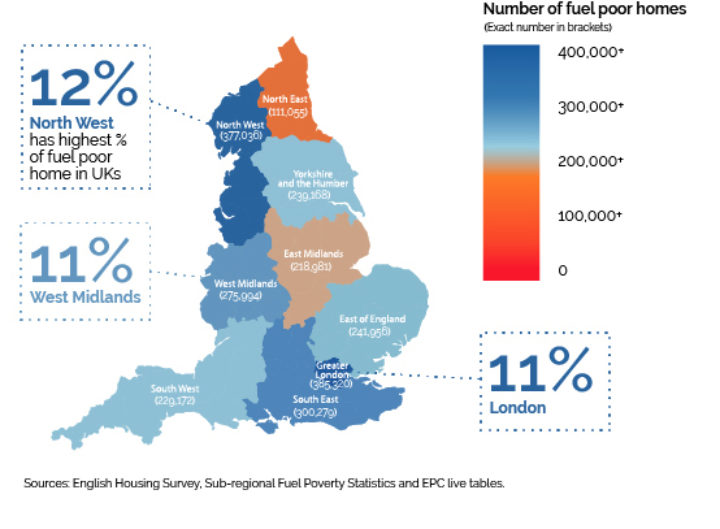

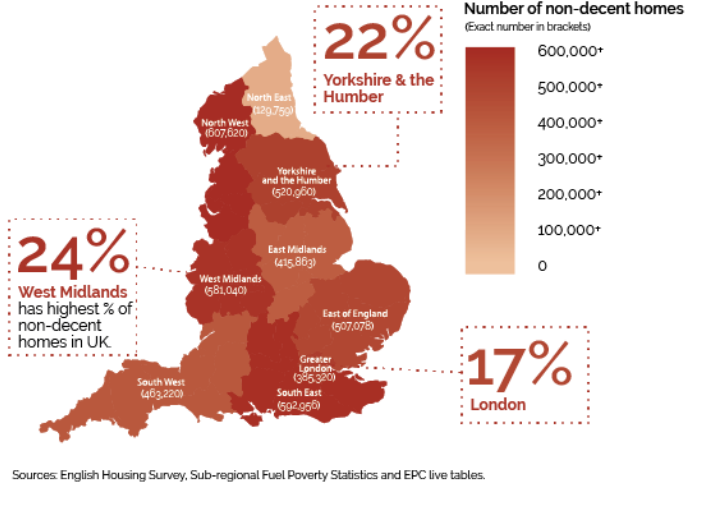

This report shows how households are disproportionately found in the North (one million homes) and Midlands of England (700,000 homes), make up 55% of all homes in fuel poverty in England.

37 of 40 most marginal constituencies are being hit harder by gas crisis because of poor housing quality.

Millions more at risk of fuel poverty

It is also likely that the gas crisis will push millions more to the brink of fuel poverty, particularly those with a low income who pay three times more proportionally on bills than those on a high income.

This surge in gas bills is due to several factors, including:

- the current geopolitics of state-owned Russian gas company Gazprom reducing gas flows into Europe amid wider tensions over Ukraine

- global demand post-pandemic driving up competition for supplies.

- poor quality housing worsening the situation.

Worsening the impacts of gas price volatility, the UK is well known to have poor quality housing, especially in terms of energy performance. Energy efficiency, through measures such as insulation limits gas demand by reducing the amount of heat wasted, which in turn cuts bills.

The current gas crisis is putting inefficiency – as expensive fuel heating is simply leaking out of walls and roofs – into perspective for much of the public and this is likely to continue as the gas crisis endures for at least the next few months.

Energy efficiency was shown to be the top local infrastructure priority for voters before the 2019 General Election, with 33% of people choosing this ahead of improving local bus services and building new roads.

Mapping the marginal constituencies worst hit

New analysis of the 40 most marginal constituencies in the 2019 election shows that 37 of them fall below the England average for adequate EPC (Energy Performance Certificate) housing standards, a total of 1.2 million homes. Sheffield Hallam is top of the list with 81%, nearly 39,000, homes below the average.

In addition, 27 of these constituencies have higher than average incidences of fuel poverty, totalling around 265,000 households. This time Dewsbury comes top with over a quarter (27%) or 11,575 fuel poor households. Constituents in these areas are being hit harder than most by the gas crisis.

This is no surprise given the state of the UK’s homes. For example, 13.5 million homes in England do not have adequate wall energy efficiency and 17 million have below the recommended level of loft insulation. Nearly 5 million homes in the UK fail the Decent Homes Standard and around 60% in England will fall below EPC Band C, the Government’s target for 2035.

However, these homes are not evenly spread across the country. The North and Midlands of England – prime targets for the Government’s levelling up agenda – contain the highest proportion of non-decent homes, as well as highest proportion of homes below the Government’s EPC target and highest rates of fuel poverty.

Renters and diasabled people disproportionately affected

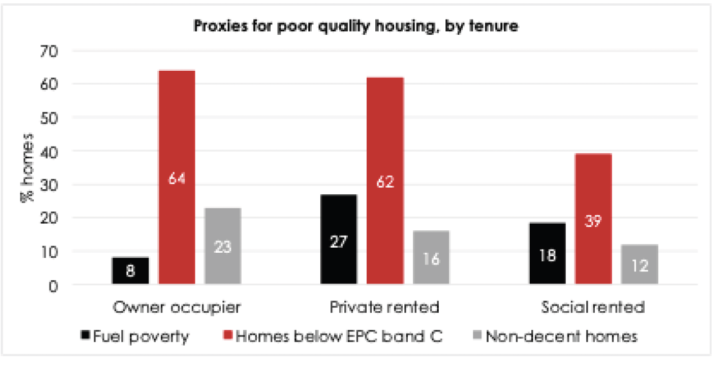

In addition, people living in privately rented homes, who tend to be city-dwellers with lower incomes, are disproportionately affected by sub-standard housing.

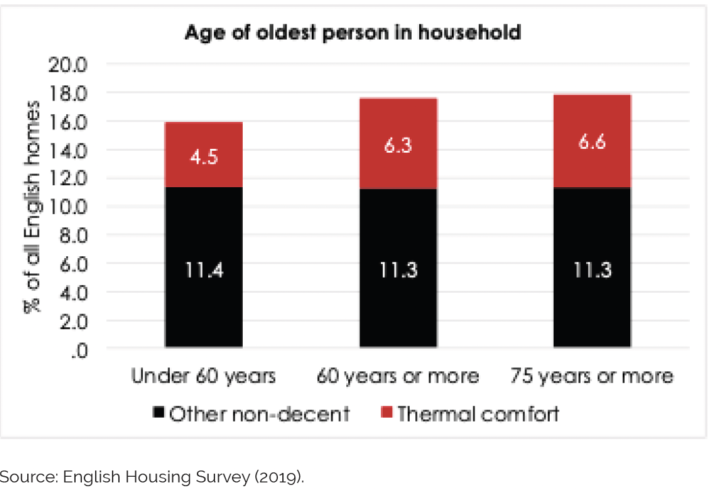

Similarly, the proportion of homes deemed to be ‘excessively cold’ rises with the age of the oldest occupant and people living with a long-term illness or disability are more often found in poor quality housing.

For example, nearly half of all non-decent homes in the North have at least one person with a long-term illness or disability.

Historic stop-start policy for insulating owner occupied homes, and a lack of incentives for private sector landlords has resulted in slow progress towards energy efficiency in these sectors to date.

Long-standing regulations and funding in social housing means this sector currently leads the way. Considering the owner occupied and private rented sectors historically have the worst levels of energy efficiency and non-decent homes, a lack of policy and financial support seemingly goes against governmental targets.

Impact of the Energy Company Obligation

One policy that has resulted in some progress in all sectors is the Energy Company Obligation (ECO), a scheme that supports energy efficiency upgrades for households with a low income or those living in fuel poverty. The scheme is due for a funding uplift from April 2022 to £1bn per annum.

This is expected to install energy saving measures into over 300,000 homes, saving on average £300 per home per year (to a total of nearly £100m in bill savings each year) and is likely to be essential to limiting bills in these households.

What does this mean for levelling up?

The Government recently formed a new Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, spear-headed by longstanding Cabinet Minister the Rt Hon. Michael Gove MP. The Department’s first White Paper, defining levelling up and setting out how it will allocate its £4.8bn budget, was published in February 2022.

Jobs and local economic prosperity are thought to be an essential part of levelling up, and analysis has shown the energy efficiency industry is expected to support over 140,000 jobs across England by 2030 to meet existing efficiency targets.

These jobs are most likely to be found in areas where there is more inefficient housing to be upgraded, for example in Wolverhampton South, where more than three-quarters of housing falls below EPC band C and nearly a quarter of homes are living in fuel poverty. Across Wolverhampton, 1,370 jobs in housing retrofits are expected to be supported by 2030 as they deliver upgrades to sub-standard homes.

Poor thermal comfort and a lack of energy efficiency in homes means that millions of Britons are living in cold, damp and unhealthy homes that can create or worsen health issues like asthma, other respiratory and cardiovascular problems, and impact mental health and wellbeing.

In fact, this report reveals clear disparities in housing quality between richer and poorer parts of the country and that the elderly, the young and people with existing illnesses or disabilities are being hit the hardest. It also shows how the most electorally marginal constituencies would benefit greatly from a housing retrofit programme that reduces bills.