Climate impacts on UK food imports

Spotlight on: climate-vulnerable countries

Last updated:

We live in a globalised world. Few systems represent that as clearly as our food system. The UK imports half of its food; around half of that comes directly from climate impact hotspots. Rapid global cuts to emissions, to limit temperature rises to 1.5°C, can avert even more dangerous impacts than we already see at 1.1 - 1.2°C.

But with every part of the world increasingly vulnerable, wealthy nations like the UK can support poorer countries to adapt, helping to protect our own food supplies whilst also ensuring those countries can continue to feed themselves.

Climate-driven extremes of hot and cold, drought and flood, as well as overall temperature rises, pose serious threats to crops and agriculture – and therefore to global food supplies.

The UK imports around half the food it consumes: 37 billion kilograms, worth £58 billion, in 2022. Approximately half of that is made up of commodities we do not grow in the UK.

*The database includes 5.7% of commodities marked as ‘unknown’ indigenous/non-indigenous status.

Non-indigenous crops represent food that cannot be grown in the UK. Indigenous food items can be grown in the UK some - or all - the year.

Non-indigenous food items as a proportion of total imports

Non-indigenous crops are not suited to our climate and soils and therefore cannot be grown at scale outdoors (for some or all of the year), requiring energy-intensive interventions (polytunnels, heated glasshouses) instead to recreate the conditions needed for the quality and scale of commercial production. Instead, it is more resource- and cost-effective to import them from countries where they can be grown at commercial scale, leaving agricultural land in the UK for crops which are suited to our climate.

The UK Climate Change Committee found that a fifth of our country’s critical supply chains originate in areas of particular climate vulnerability; that rises to half in the case of our food supply chains.

UK trade statistics show that 16% of our food imports - worth £7.9 billion - came directly from nations with low climate readiness last year, i.e. those that are not only exposed to climate impacts, but also lack capacity and preparedness to adapt and respond.

Countries with low climate readiness that export food to the UK, by size of import value

The true number is complex to calculate, but almost certainly higher, as many processed products (including those from EU nations like Swiss chocolate or Italian coffee) contain raw materials that also come from low climate-readiness countries. Three quarters of those imports were commodities that we cannot or do not grow at home.

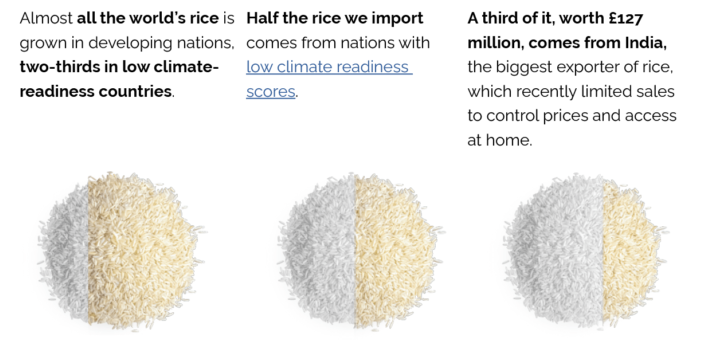

Our top imports from climate vulnerable nations include staples like rice.

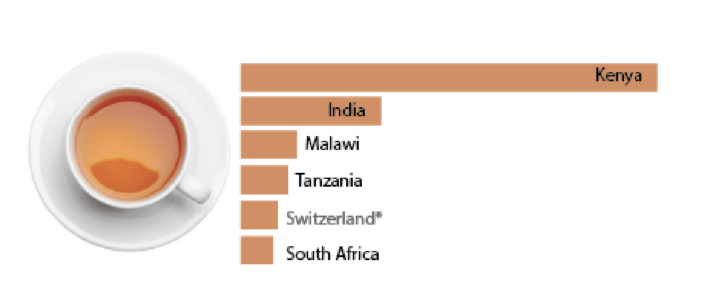

Climate change threatens the British cuppa and our morning coffee, with almost all our tea imports coming from climate hotspots and most of the world’s coffee being grown in areas of low readiness.

Countries with highest value tea exports to the UK

Cocoa is similarly at risk, with four fifths of the cocoa beans we import coming from Ivory Coast; as the world’s largest producer, they also likely supply EU nations with beans used in chocolate products we also import.

The sugar in our tea, coffee and chocolate is more complex, but two thirds of the cane sugar we import comes from low climate readiness countries. In the UK, sugar prices have risen more than 50% to July 2023; a rise fuelling wider food inflation.

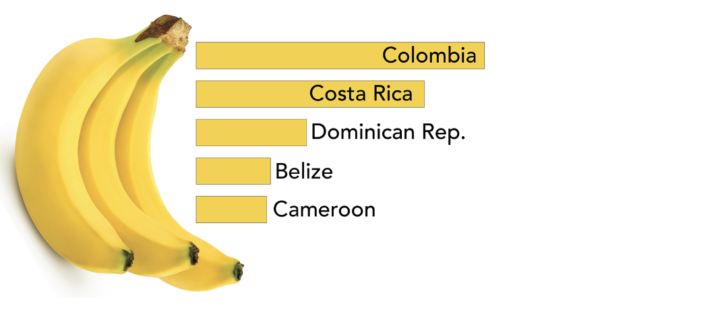

Fresh produce is threatened. Three quarters of the UK’s bananas, worth £379 million, come from low climate readiness nations. Almost all the global trade in bananas is in one cloned variety, vulnerable to a fungal disease; a risk that could grow as temperatures rise. Two thirds of avocados, nearly all mangoes and guavas, and more than half our melons also come from climate vulnerable countries

Countries with highest value banana exports to the UK

UK livestock can be hit by climate impacts further afield. We import over £300m worth of soya, almost all from Brazil. Three quarters of it is fed to farmed animals in the meat and dairy industries.

Extreme weather reduces quality and harvests, leading to less food available for consumers, at higher prices. UK households have already seen average food price rises of £400 last year, driven by climate impacts and fossil fuel price hikes.

The growing threat from climate impacts will continue to add to this, exacerbating the cost-of-living crisis.

It is sometimes suggested we can replace commodities at risk by switching suppliers, repurposing land to grow more here, or even growing new foods as the UK warms. However, climate impacts do not respect borders, and switching suppliers does not avoid higher prices caused by shortages.

Nor are climate impacts constant. Repurposing land or growing crops suited to warmer climates has knock-on impacts for existing land-use and soil quality and assumes a warmer UK climate is also more constant. However, the UK’s cooler and wetter summer of 2023 stood in sharp contrast to the year before, when we hit a new record of just over 40°C. The 2022 drought harmed UK crop yields and, along with high energy and fertiliser costs, added to pressure on British farmers and agriculture.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s sixth assessment report concluded that climate change impacts are worse than forecast, and worsening as the planet heats. Currently, at just over 1.1°C of temperature rise, climate change is driving more extreme weather, including hotter, longer and more frequent heatwaves. 2023 has seen the hottest month ever in July, and the hottest northern hemisphere summer, as land and ocean temperatures soared to new highs in parts of Europe and North America, and even in parts of South America during Southern Hemisphere winter. Many parts of Asia, including India and Pakistan, have seen record high temperatures and severe flooding – all before the return of El Niño has even made itself felt.

Even if the world succeeds in keeping temperature rises to 1.5°C, food producers worldwide (including in the UK) need to adapt to these new climate extremes. That can include measures like planting crops in the shade of another plant, to protect it from heat, for example. But if we do not limit temperature rises, then impacts from climate change increase sharply and even become irreversible. For example, it is predicted we could completely lose coral reefs at 2°C of warming – a habitat critical to fish, a source of at least a fifth of more than 3.3 billion people’s daily protein intake.

Climate impacts hit poorer, less developed nations harder than wealthy, industrialised nations with better access to global finance. Livelihoods are threatened for farmers in climate vulnerable nations, but so is food availability as many of these commodities are also staples in the countries affected.

Financial support and investment from wealthy nations like the UK speeds the clean transition and helps poorer nations adapt to climate impacts. Grants and loans for development and climate action, as well as private investment in clean energy solutions and adaptation, can safeguard critical supply chains, as well as protecting lives and livelihoods in climate vulnerable nations.

The UK has cut its Official Development Assistance (ODA) budget, and a growing proportion is spent in-country rather than overseas, on temporary accommodation for asylum applicants. Although developed nations have not yet made good on their 2009 promise of $100 billion a year in climate finance for poorer nations from 2020, the UK recently reaffirmed its commitment of £11.6 billion in climate finance over five years to 2025/26. COP28 in December this year will look to wealthy nations to progress the commitment made last year, at COP27 in Egypt, to establish a finance facility for the most climate vulnerable nations that will pay for loss and damage from climate disaster.

Adaptation helps to cope with the damage already done. The only means of stopping climate change, and limiting further temperature rises, is mitigation: to phase out fossil fuels and speed up the clean energy transition to reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions globally by mid-century.

Climate change is a global threat, with impacts felt in every country in the world. Solutions are also global.

The IPCC is clear we already have the means to achieve net zero, and that doing so is cheaper than the ever-growing costs of coping with climate impacts. For the UK, along with other wealthy, developed economies, this includes living up to our international commitments – also increasingly a matter of protecting our national security and security of our food supplies.