Europe Steels the Deal

UK falls even further behind in the race to clean steel

Last updated:

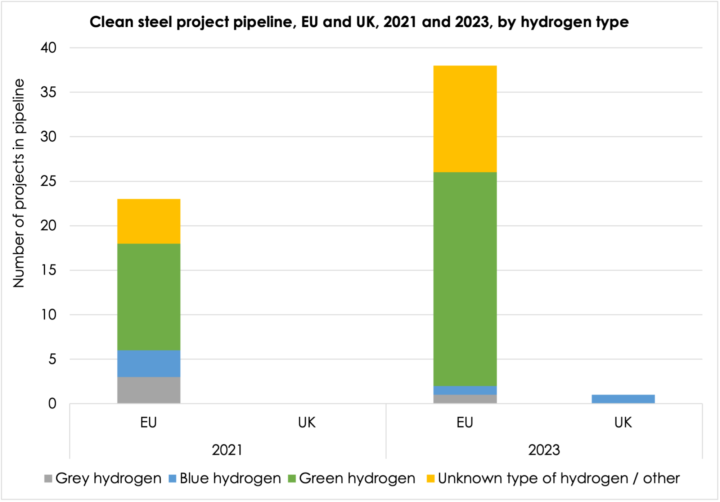

This report analyses changes to the European and UK clean steel pipelines between 2021 and 2023. It finds that the EU has increased the number of clean steel projects planned or in progress to 38 in 2023, up from 23 in 2021. Meanwhile, the UK has added just one, up from zero.

In addition, the EU has doubled the number of projects that use green hydrogen while those that use blue hydrogen are down by two-thirds. In contrast, the only project that the UK has added is based on blue hydrogen.

Introduction

Steel is the third most abundant manmade material on Earth and the second most traded global commodity. High-quality steel has been manufactured in the UK for over 200 years.

Despite around half of the UK’s steel being imported (54%), the economic output of the sector adds £2.4bn to the UK economy per year and around 40,000 jobs are supported country-wide. In communities where steelworks are located such as Aberavon (Port Talbot) and Scunthorpe, the steel industry supports 13% and 7% of local jobs in 2021 respectively.

In May 2021, the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit published Stuck on the starting line: How the UK is falling behind Europe in the race to clean steel, which showed that while Europe had plans for 23 clean steel plants in the pipeline, the UK had ‘no concrete plans for trialling hydrogen-based primary production and only vague plans for a single carbon capture-based project.’

Two years later, amid economic uncertainty for the UK in the form of a possible recession, flatlining productivity and the steel sector calling for Government support, this report provides an update to the 2021 analysis. It considers how the pipeline for clean steel plants has changed in two years in both the EU and UK and which clean steel technologies are receiving the most private and public sector investment.

The shift towards green steel

There is a growing demand for green steel. Members of the SteelZero initiative for example ‘make a public commitment to buy and use 50% low emission steel by 2030, setting a clear pathway to using 100% net zero steel by 2050’. They include car manufacturer Volvo (alongside its aim to only sell electric cars by 2030), as well as offshore wind giant Orsted.

Discussions are ongoing in the US and EU about ‘carbon border adjustment mechanisms’ that would add costs to non-green steel imports.

“…the industry is at a crossroads. Down one path lies the slow decline of steelmaking, withplants becoming obsolete. This would lead to the loss of the UK’s self-sufficiency and resilience in steel, as well as thousands of well-paid jobs in steel communities. The impact would also ricochet across a complex supply chain which employs everyone from engineers and electricians to architects and lorry drivers.

Down the other path is a new era in which we transform the steel production process to make it fit to face the ever-changing challenges of society. This an exciting opportunity, which would secure steel supplies for the UK’s future, supercharge levelling up and create well-paid, high-skilled jobs. Critically, it would be an essential part of the UK’s drive to meet its net zero objectives. This is green steel.”

Technologies for decarbonising steel

Historically, primary steel production involves the reduction of iron ore in a blast furnace using coke and coal to produce a liquid metal. Steel is then produced by reducing the carbon content of the metal by adding oxygen via an oxygen furnace. Both of these processes emit CO2.

It is widely thought that primary steel production could be decarbonised by using hydrogen to directly reduce iron with no need for a blast furnace as the reaction would take place in a solid state. The metal would be converted into steel in an electric arc furnace instead of a basic oxygen furnace, with both processes vastly reducing the carbon emissions from steel making.

During the transition to this method of steel production, hydrogen could be injected into existing blast furnaces to reduce the iron. However, this would require more energy and as such higher temperatures which could damage the inside of the blast furnace, so it is not viewed as along term solution.

Secondary steel can also be made by melting scrap steel in an electric arc furnace to drive off any impurities and create new steel products. The emissions from electric arc furnaces largely depend on the carbon intensity of the electricity used. Around a fifth of the UK’s steel (18%) is made by this method. For comparison, in the US it is over 70%.

Analysis

Analysis of the Leadership Group for Industry Transition’s Green Steel Tracker finds that the number of green steel projects either planned or in the pipeline in Europe has risen to 38, up from 23 two years ago. In contrast, the UK has added just one, up from zero.

Not only has the overall pipeline of clean steel grown in the EU, but the number of planned steel projects that use green hydrogen (made by splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen) has doubled in the last two years. Meanwhile blue hydrogen (made by splitting natural gas in steam methane reformation, with carbon capture technology absorbing some, but not all, of the residual emissions) projects in the EU have decreased by two-thirds (-67%).

The levelised cost of grey and blue hydrogen has increased as gas prices surged in 2022, with the Carbon Tracker Initiative finding that investment and plans to build green hydrogen have been accelerated as a result. However, the only UK based clean steel project in the pipeline expects to use blue hydrogen and carbon capture and storage (CCS).

The analysis shows the UK is clearly behind Europe on its plans to decarbonise steel, and has no planned green steel projects.

Green steel in Germany

In Germany alone, there are nine green hydrogen-based steel projects planned, and one grey hydrogen plant in operation. Grey hydrogen is made using steam methane reformation but without the CCS technology to capture the carbon emissions, so will need to be replaced by green hydrogen in the transition to net zero.

Germany’s 2020 Steel Strategy stated that “acting now to decarbonise steel production is necessary in order to make sure that this key industry is still prospering in 30 years' time,”.

Overall, it is thought that Germany has invested €8.5bn in decarbonising its steel industry, made up mainly of a €2bn Clean Steel Fund plus an additional €5bn committed in 2021, with the latter to be spent between 2022 and 2024. In 2022, another €1bn was committed by the EU Commission for Germany’s Salzgitter plant to use green hydrogen. This has helped to leverage private sector investment.

In Germany, energy intensive industry (EII) users will be supported by a €49bn grant scheme to combat higher energy prices caused by the war in Ukraine, with the aid expected to be given out before the 31st December 2023. Up until the end of September 2022 EIIs could also claim up to €50m each as a response to increased gas and electricity bills, as part of an aid package worth £5bn.

Commitments in the UK

At the moment, the only clean steel project in the pipeline in the UK is as part of the Zero Carbon Humber initiative, which aims to create a decarbonised industrial cluster with partners including British Steel. The project will look at introducing blue hydrogen for EIIs, including British Steel’s Scunthorpe plant.

In contrast to Germany, there has been uncertainty around the levels of support for the UK steel industry. Although it was announced before the General Election in 2019, the £250m Clean Steel Fund remained unspent in October 2022. The fund is due to be allocated this year.

However, it has been rumoured that the Government is in talks with Tata Steel and British Steel about a possible package, worth £300m each, that would help secure jobs at their Port Talbot and Scunthorpe plants respectively. Reports suggest that the investment would be linked to steps to decarbonise steel manufacturing but progress on and conditions of the package remain uncertain.

Energy costs

Electricity prices have risen sharply in the two years since as a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, in part pushing up the gas price. In January 2023, during a debate around EIIs and steel energy costs in the House of Commons it was claimed that British Steel in Scunthorpe is paying nearly £1 million a day for electricity, “the cost of electricity having risen tenfold since 2021”.

A 2018 UCL study found a number of reasons for the disparity in electricity prices between the UK and Europe. A lack of long-term contracts for energy intensive users, a more hands-off approach to shielding industry from policy and network costs compared with neighbouring countries, and a lack of coordination when integrating renewables into the UK system were identified as factors leading to higher energy costs in Britain.

The UK currently has a marginal pricing system for wholesale electricity, where gas usually sets the price for all generation despite renewables being cheaper. Recent soaring gas prices have therefore prompted calls for the acceleration of the Government’s Review of Electricity Market Arrangements to decouple the prices of gas and electricity. As electric arc furnaces and the production of green hydrogen both rely on electricity, it is thought that this could reduce the price of green steel.