All eyes on the Energy White Paper

The impending sector-defining document is a time for ambition and for action to underpin rhetoric

By Jonny Marshall

Share

Last updated:

The next step in the endless drip-feeding of energy and climate policy is the Government’s Energy White Paper, a document that will set the overall direction for an energy sector that is currently mid-revolution.

The 13 years since the last White Paper landed have brought unimaginable change, with this version expected to deliver the strategies, visions and targets needed to underpin the UK’s shift to a net zero carbon country, backed largely by an expanded and decarbonised power system.

Here are some of the key things to look out for when it is finally released.

Nuclear go-go

Making the headlines will be a decision on nuclear, with Sizewell C expected to be given the green light.

The Government re-confirmed its support for large nuclear in the recent Infrastructure Strategy, and it is no secret that civil servants and regulators have been beavering away on the finer details of how a new project can be funded for months now.

The pros and cons of nuclear have been debated to death, so will be sidestepped here. But what is interesting is what this expected decision means for the wider sector.

Pulling out all of the stops to bring down costs, the Government seems likely to take on an equity stake in the project to get it started, as well as backing a new funding model for the longer term.

The last time that the UK Government owned a stake in a power plant was back in 1995, when the final stages of privatisation saw the remaining 40% of Powergen sold off. The state hasn’t owned a nuclear fleet since the transfer of assets to Nuclear Electric in 1990, a cool 30 years ago.

Since then there has been a relentless focus on the private sector delivering new kit for the power system, spurred on of course by policies to give some industries a kick start.

But there remain a number of technologies that have yet to reach full potential and would be given a huge boost were the Government to show support on a comparable scale as it is set to for Sizewell C.

If I’d spent recent years trying to make the finances of tidal power work, I’d be asking why similar support hadn’t been made available. And while the wind industry is now a roaring success, would more companies be based in Britain if the Government had shown such backing from the get-go?

Impact

With the Sixth Carbon Budget and Climate Action Summit both imminent, the Government will be keen to deliver a message that will impress both national and international onlookers.

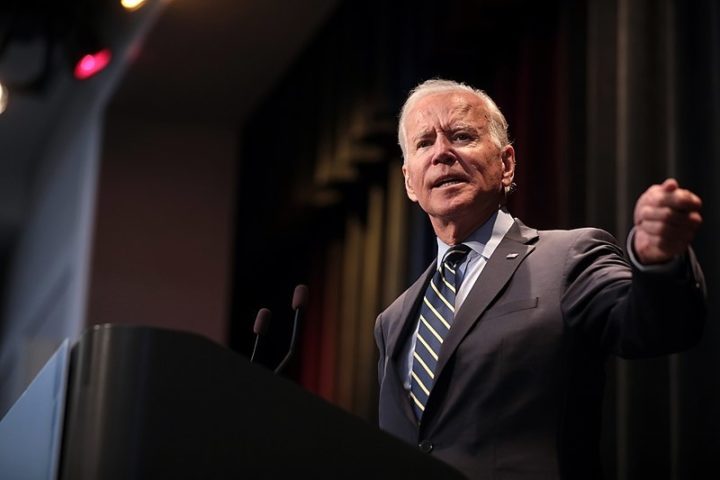

The apparent ‘Bidenisation’ of British policy could take another step forward with an announcement to match US ambition on power sector decarbonisation, a significant ramp up from current plans.

Matching the incoming president's target of a zero carbon power sector by 2035 would cause the sort of splash that the Johnson Government would be looking for. Keen eyes, however, will be ensuring that any pledges are underpinned with by a shift from gas to renewables, rather than using negative emissions to offset unabated fossil fuel use.

National Grid scenarios show that a net zero power system by the early 2030s is within reach, although it has been criticised for an over-reliance on BECCS. One might expect some of the names associated with a public push on this goal to hope for a removals-heavy outcome.

An alternative, and potentially more credible, route would bring clarity on the future of renewables, a clear plan for frequent and regular CfD auctions, action to re-ignite the domestic solar market, and, ideally, an end-date for unabated gas generation.

Dynamism

The much-jumped-upon system warnings from National Grid in recent weeks highlight the need for widespread change in the rules and regulations that underpin Britain’s electricity system.

As coal plants have been replaced by wind turbines at a record pace, the governance that fundamentally decides what gets built where and when has failed to keep pace.

Rules that slow down the deployment of storage by failing to recognise its full system value, the absence of proper frameworks for flexibility markets needed to make the most of severely-underused technologies like DSR, and the complete lack of backing to make domestic demand more dynamic need to be fixed quick-sharp so that the grid can accommodate ever-more cheap and clean renewable energy.

There have been clear hints from Government that a change in Ofgem’s remit could be imminent, ensuring that actions from the regulator stop hindering decarbonisation; that more is needed to make markets work for flexibility; and that ways of boosting smart meter use (paying households to have one installed?) are all sorely needed.

All of this is expected to feed into the top-level direction set in the White Paper.

Pipes and wires

Decisions are also needed on the physical assets that keep our lights on and our homes heated. The White Paper comes at a crucial time for the gas and electricity grids, both of which need direction over their role in a net zero UK.

The Government’s Ten-point-plan included a pledge to increase hydrogen blending across the gas network, yet many see a limited role for the ever-hyped gas.

Blending on this scale (20% by volume) will need widespread upgrades to the gas grid, investment that could prove futile if future uses of hydrogen are largely confined to industrial uses rather than for domestic heat, as seems likely.

Proper targets on hydrogen may not be forthcoming until next year, but the language used throughout will give a clue to Government expectations for scale and ambition.

Reform on network investments is impending, ensuring that upgrades work best for the system rather than just for a regional grid. The electricity system is in need of strengthening, with clarity and support needed to kick start build out of an extensive EV charging network.

Heat and buildings

Energy efficiency is having something of a day in the sun at the moment, starring the Chancellor’s Summer Statement and featuring prominently in the society-wide pushes for a green Covid recovery.

The White Paper will need to bring long-term clarity to policies to decarbonise British homes, on the future of the current schemes (and of those in the manifesto but yet to kick into gear), as well as ways to incentivise the market to deliver building upgrades, in addition to the pivot to clean heat.

At some point in the 2030s, Britain will install its final gas boiler. The White Paper is vital in ensuring that policies, funding, public awareness and markets are all well established by then. This has been seen as something of a lightning rod within Government, however, a surge in conversations around clean heat over the past year or so should assuage some fears.

Of course, this list is far from exhaustive, the last White Paper ran to more than 300 pages. The White Paper is not a final document, instead a starting point that will spawn a litany of consultations, plans and strategies, all of which are subject to change following stakeholder feedback.

What is vital, though, is that the top level ambition – getting the UK on track to net zero – is there, and that much needed detail and direction is provided to underpin the rhetoric coming from Downing Street.

Share