Future Homes Standard: no time like 2023

Announced then de-announced, what would be the impacts of a 2023 Future Homes Standard?

By Jess Ralston

@jessralston2Share

Last updated:

Underneath the headlines on electric cars, one of the most intriguing aspects of the Prime Ministers 10-point-plan was the announcement and then de-announcement of the date at which new homes would no longer be connected up to the gas grid.

The Government has been criticised for allowing millions of net zero-incompatible homes to be added to the nation’s housing stock; the Future Homes Standard was supposed to remedy this.

Now though, all eyes are on a shorter deadline, and on the standards themselves, which were considered as not exactly up to par when first proposed.

Ambition

Boosting the rate of housebuilding is a central pledge from Government, from the approximately 250,000 new homes built in England and Wales every year to 300,000 new homes each year by the ‘mid-2020s’.

These figures highlight how costly a delay would be. 2023 will already be seven years since Zero Carbon Homes was supposed to come into effect – during which time around 1.8 million new homes are likely to have been built. Another two years on top will see at least half a million more.

The average new home built 2019 emitted around 1.5 tonnes of CO2 per year, as families used energy to warm rooms and heat water. A 75-80% reduction would slash this to between 0.3 and 0.4 tonnes.

The UK is set to miss its 4th and 5th carbon budgets. Failing to maximise emissions reductions through the Future Homes Standard could make it harder to get back on track.

Secondly, the energy savings are likely to result in a major win for consumer’s wallets. The Committee on Climate Change (CCC) estimates that around £85 per year could be saved from the introduction of ultra-high levels of energy efficiency and a heat pump in new homes.

Thirdly: jobs, jobs, jobs. Modernising the UK’s heating infrastructure is set to support huge levels of employment from now, to mid-century, and beyond. The newly set target to install 600,000 heat pumps in the UK from 2028 will require a skilled workforce, and regulations that will lead to hundreds of thousands of heat pumps per year from 2023 will help build this.

The Heat Pump Association estimates that in first year of the Future Homes Standard, the potential number of low carbon heating installers needed could increase by more than half on the year before. If brought forward, this could mean around 10,000 additional jobs could be created by 2024.

A strong signal will also pique the interest of the UK’s 140,000 gas safe engineers, and if backed by an effective and accessible training programme, could pave the way for the reskilling needed to meet the CCC’s target of 1.5 million heat pump installs by the mid-2030s.

Lastly, increased awareness and acceptance of new heating technologies – already identified as a major barrier – will benefit the transition to clean heat. Starting with new builds, understanding of new systems will be improved as the technology is increasingly deployed. Word of mouth and increased social acceptability, tied in with effective support from Government, could lead to more Brits choosing a renewable system next time the boiler breaks down.

Gaps

Despite this wealth of positives, the Future Homes Standard does need some tinkering.

The overall ambition has raised concerns, particularly given a zero carbon homes standard was suggested way back in 2005, and some gaps remain. For example, the CCC stated that the steps ‘do not go far enough to reduce carbon emissions…stronger standards will serve future occupants better’, while the Mayor of London warns that it ‘should be a net zero carbon standard’ to reflect the scale of the 2050 challenge.

Industry bodies too, including the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) and London Energy Transformation Initiative (LETI), have indicated the proposed Future Homes Standard is not stringent or ambitious enough.

Another sticking point is the centralisation of standards, removing the ability for local authorities and councils to set higher targets, as is currently the case in a host of British towns and cities. In fact, the proposed standards represent a downgrade on some already in existence.

Currently, 300 of 404 local authorities have declared a climate emergency and most large UK cities have net zero targets set in stone. In places like Telford, which was one of the fastest growing towns between 2011-2019 (12% growth) and has a net zero goal for 2030, the ability to push for higher standards is likely to be crucial to meeting their accelerated aim.

Delay

One mooted reason behind the Future Homes Standard’s slow progress is the damage done to the housebuilding sector during Covid-19.

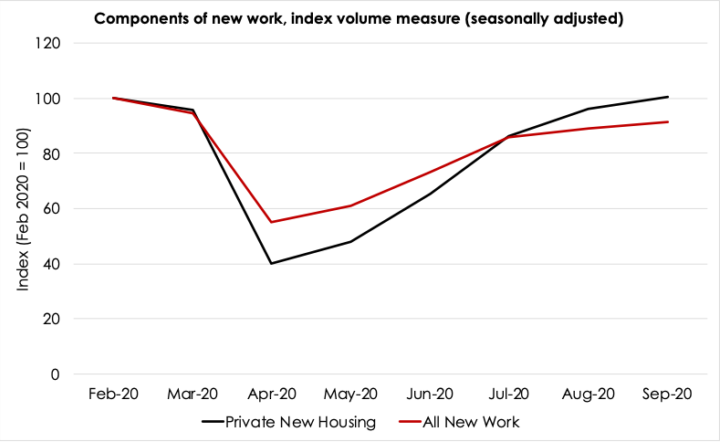

The number of new homes built during Q2 of 2020 was just half that of the same period in 2019, as construction sites were closed and employees told to stay at home.

Since then, though, private housing output levels have rebounded to those seen pre-pandemic levels, while orders placed for 2021 are ‘healthy’ – up 40% for Redrow, for example.

There will, of course, be an impact on annual sales – Savills estimate that 84,000 fewer homes will be delivered this year than last – but building rates recovering means hundreds of leaky homes are being added to the nation’s building stock each and every day.

The Future Homes Standard is seen – quite rightly – as a vital first step in tackling emissions from buildings. Recent climate announcements from Government have struck the right tone, but have received criticism for not being backed by effective policy. Increasing ambition on the energy performance of new homes is a chance to start to put that right.

Share