Climate risks: Time to mend the roof?

UK climate advisors paint an increasing wet/dry/hot future - but what can a broke government do about it?

By Richard Black

Share

Last updated:

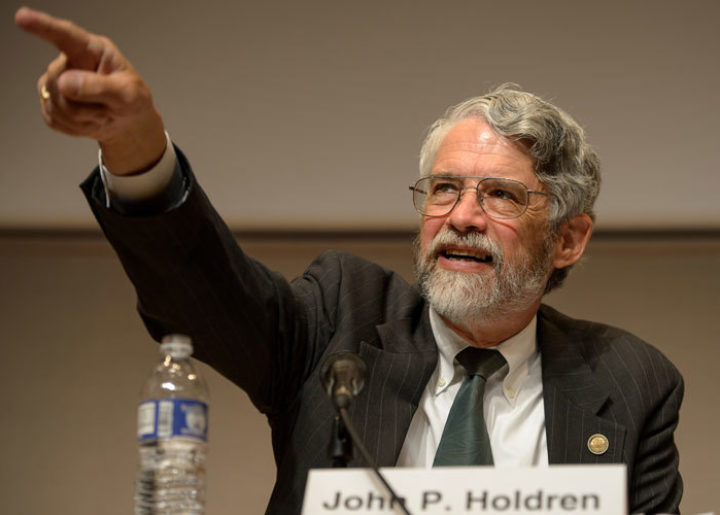

About a decade ago, John Holdren, now President Obama’s chief science advisor, coined a lasting phrase about climate change.

“We basically have,” he said, “three choices: Mitigation, adaptation and suffering.

“We’re going to do some of each. The question is what the mix is going to be.”

The quote came to mind when reading through the latest report on climate change risks to the UK, which the government’s statutory advisor, the Committee on Climate Change, has just put into the public domain - and which it will now send to the government of the next Prime Minister, Theresa May.

So what does it say?

“The greatest direct climate change-related threats for the UK,” it says, “are large increases in flood risk and exposure to high temperatures and heatwaves, shortages in water, substantial risks to UK wildlife and natural ecosystems, risks to domestic and international food production and trade, and from new and emerging pests and diseases.”

That’s quite a list.

Wet or dry?

The biggest risks pertain to water – various combinations of having too much or too little, in the wrong amounts or in the wrong place or at the wrong time.

Broadly speaking, projections indicate that UK winters will become wetter and summers drier; the already dry south will become drier still; and more rain will come in heavy storms rather than gentle drizzle.

Within the last year alone, we've seen the extreme weather part of these projections materialising, as scientists showed that climate change made last December's damaging storms in northern England and southern Scotland more likely.

Sea level is rising globally, and UK waters are no exception.

The rate of sea level rise accelerated around the year 2000. It is now about 3mm per year, and may well accelerate again as land-based ice in various places continues to melt. The changing climate is also likely to bring an increase in storm surges, with the rising incidence of heavy rains bringing a higher risk of flooding.

On the dry side, the report says: “By the 2050s under high climate change and high population growth scenarios, demand for water could be more than 150% of the available resource in many catchments across the UK.”

In layman’s terms: there won’t be enough water in all places for all of the people all year round. In areas of England, Scotland and Wales, extracting enough water for human needs will not leave enough for nature, for a quarter of the year. In dry areas such as East Anglia, farmers will increasingly need irrigation – but as things stand, there won’t be enough water with which to irrigate.

Then there’s heat, While many of us would like old grey Blighty to be a bit warmer for most of the year, one of the corollaries is an increase in heatwaves. Conditions such as those we saw in 2003 are likely, the report concludes, to be normal in the 2040s.

How far - and how much?

Now, with this kind of climate forecast, a key question is whether society can prepare adequately; whether buildings, roads, farms and other resources can be “climate-proofed”. The answer from the Committee is: “It depends”.

Most obviously, it depends on how much we’re prepared to spend, and how far climate change progresses.

With infinite amounts of money you might in theory be able to prepare for any changes coming down the line; but real life is a little different.

And on the extent of climate change, the Committee concludes: “At global average temperature rises approaching 4°C, impacts become increasingly severe and may not be avoidable through adaptation.”

At 4ºC of global warming, forecasts say damages from all kinds of flooding (coastal, rivers and surface water) remain high, however much defences and other measures are put in place. Meanwhile, “potentially irreversible impacts to the natural environment are projected.”

1.7 trillion troubles

Now: this report isn’t just an academic exercise. It’s aimed squarely at helping government to decide how to spend money in areas such as flood defences; how to design for the future, for example by preparing hospitals to keep vulnerable patients cool in higher summer temperatures; and what regulations to enact on activities such as building, to minimise risks.

But here’s the rub. Public money is tight; in the political excitement over Brexit and party leaderships, it’s been almost forgotten that the country is £1.7 trillion and rising in debt. The market reaction to Brexit is likely to increase rather than decrease these economic troubles, as evidenced by the government’s decision to abandon plans of achieving a budget surplus by 2020.

On flood protection, despite the assertions of successive Chancellors, governments haven’t been spending enough to “fix the roof” while “the sun was shining”. So what chance of fixing it now that the rain is splashing through the cracked tiles and flooding out the floor below?

But here’s where we return to John Holdren’s triple choice: because the less adaptation we do now, the greater the suffering in future.

The adaptation/mitigation combo is harder still. Adaptation spending brings rewards locally, and relatively quickly (anything from instantly to several decades away). The payback on mitigation, on reducing emissions, is longer, and diffuse; what any nation does to cut emissions is felt everywhere in the world.

So the short-term case is always to do as little as possible, and the long-term case to reduce emissions as much as possible, with adaptation somewhere in the middle.

Yet, the more emissions rise, the greater the amount of adaptation needed (or the amount of suffering) in times ahead; and we live in an increasingly interconnected world, where the supply chains of UK supermarkets stretch to Africa and Asia, and in which Brexit has just re-drawn the list of countries where Britain needs to find favour.

There has in reality always been a fourth option to John Holdren's list: to stick one’s head in the sand, stick one’s fingers in one’s ears, and harrumph loudly that this climate change malarkey is all nonsense made up by bloody experts.

Theresa May, by all accounts, has never adhered to that line of thinking.

Over the next six months, her government will be incorporating the Committee’s report into its own programme for climate adaptation. In parallel, it will also be producing a Carbon Plan – a programme for reducing greenhouse gas emissions over the next 15 years.

Everything I hear suggests that her government will take both of those tasks seriously. But that doesn’t mean it will spend every penny that really needs spending; which will, in turn, leave future generations with a greater legacy of climate impacts.

Choices, choices, choices. Who’d be Prime Minister, eh?

Share