Marrakech: Fewer fireworks, but flame still burns

Next week's UN climate summit will be less exciting than last year's - but important nevertheless

By Richard Black

Share

Last updated:

It seems extraordinary that less than a year ago we were living in a world without a global climate change agreement under which every country pledged to constrain its greenhouse gas emissions.

Yet, before last December’s UN climate summit in Paris ended, that was the case. The last time youngsters wheeled out their Jumping Jacks, demanded pennies for their Guys and wondered how high those rockets really go, the majority of countries carried no obligation at all to restrict their contribution to global climate change.

So it’s absolutely valid to take a moment this weekend and reflect on the Paris Agreement, which entered into legal force on Friday – and to look ahead to the task of implementing it, which begins, at international level, next week, at this year’s UN summit in Morocco.

Profound change

Deciding what to make of the Paris Agreement isn’t entirely straightforward; opinions do vary, and different interpretations are valid.

I would argue that its single most important aspect is its very existence. The last attempt to secure a global emissions-cutting deal, in Copenhagen in 2009, was – let’s be plain – a car-crash. As I wrote at the time, there were a number of reasons why – but the simplest and most important was that the big players didn’t want to make a global agreement that restricted carbon emissions.

Six years later, they did. And then they ratified it so quickly as to bring the Agreement into force faster than anyone had predicted, spurred partly by the prospect of a Donald ‘global warming is a Chinese hoax’ Trump presidency, but more pertinently because with temperature records being broken month after month and renewable energy costs coming down month by month – well, why wouldn’t you?

One of the reasons why Paris succeeded where Copenhagen failed was that China and the US, the world’s two biggest emitters, made common cause, stood side by side and essentially challenged the rest to follow.

China is the more interesting and instructive end of the equation. And it’s abundantly clear to anyone but those who don’t want to see that there has been a profound shift in Chinese thinking about its development pathway, with a prioritisation of quality over quantity in economic growth.

As we detailed last year in a joint report with the respected bulletin ChinaDialogue, ‘green’ growth now works for China. So far, the main trends have been to make energy use more efficient, to halt the expansion of coal burning, and to start building a low-carbon electricity system based on renewables, nuclear reactors and some innovative market and regulatory measures.

You can sum it up in the meme that whereas China used to build two coal-fired power stations per week, it now erects two wind turbines per hour. It’s true, but misses the profundity of the broader change.

Self-interest

China illustrates the over-riding rationale of the Paris Agreement. No country is going to sign up to something that runs counter to its national interest; and for China and many other nations, the Agreement reflects national plans that were already in implementation, on the drawing board or on the wish list.

But if that were all, you would be entitled to ask what is the point of making a global deal? Why not just have each country doing its own thing?

The Paris Agreement does a number of things, including:

- It gives governments and businesses confidence in the direction of travel

- It contains obligations and mechanisms for increasing the pace of emission-cutting

- It will ensure resources are put in place to help the poorest countries prepare for climate impacts and leap-frog the fossil fuel era

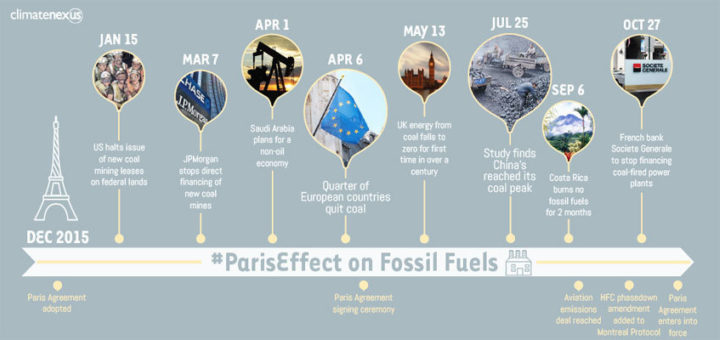

So, it's not been a surprise - though it is worth remarking - that fossil fuel investors have seen an unprecedented set of problematic issues arise in the months since Paris.

And yet, and yet…

As the UN Environment Programme detailed last week, the cumulative effect of countries’ emission pledges, even if implemented in full, take us to a 3 Celsius world, not the ‘well below 2 Celsius and preferably 1.5 Celsius’ one that governments promised to deliver.

As seven oil and gas majors showed on Friday in an announcement that fell so pathetically short of their declared ambition to be ‘part of the solution’ as to be frankly risible, belief that ‘business as usual’ can continue as though the Agreement didn’t exist remains high in some quarters.

As Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull is demonstrating through his backing for the giant proposed Carmichael coal mine in Queensland, many governments are acting as though simply having the Paris Agreement is enough to deliver it.

So… in Morocco next week, the hard work begins.

Back to the small stuff

Quite a few of the important Paris ingredients lack detail; and the most important job in Marrakech is for national delegations to make progress on some of them – for example:

- How, precisely, will the process of monitoring and verifying countries’ adherence to their emission-cutting pledges work?

- How will the process work whereby governments review progress in 2018 with a view to tightening emission cuts?

- What, practically, do the clauses on ‘loss and damage’ – the idea that rich nations compensate the poorest for impacts from past emissions – imply?

How much progress they’ll make isn’t clear. For one thing, there’s no non-negotiable deadline this time, and no political pressure from heads of state. There’s also the issue that neither governments nor the UN climate convention secretariat expected the Paris Agreement to come into force so quickly – hence, the ground for detailed discussions hasn’t been prepared as thoroughly as it might have been.

You can never tell for sure, but my bet is on the next two weeks turning out to be fairly dull – devoid of major announcements, full of arcane detail, with quite a lot of posturing on countries’ detailed positions thrown in. By the end, I suspect many of those there, especially from environmental organisations, will be feeling somewhat let down, and asking whether the magic of Paris fell out of a plane somewhere on the short hop to Marrakech.

If so – well, so be it. Not every firework shimmers like a peacock’s tail – some are much more workaday. They can still be a valuable part of the whole display; and the sky itself is still richly illuminated by the historic agreement governments made in Paris.

We may not see such incandescence again until 2018 - but that doesn't make Marrakech a worthless squib.

Share