Clean Growth Strategy: Delivering what the UK needs?

What should we be looking for in the government's long-awaited climate change roadmap?

By Richard Black

Share

Last updated:

After a delay of nine months and at least three changes in its title, the government will publish its Clean Growth Strategy tomorrow (Thursday).

So, what is the Clean Growth Strategy? What does it have to deliver? And will it match up to expectations?

What is the Clean Growth Strategy?

Legally, it has one job: to tell us how the government will meet the target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 57% (from 1990 levels) during the period 2028-2032.

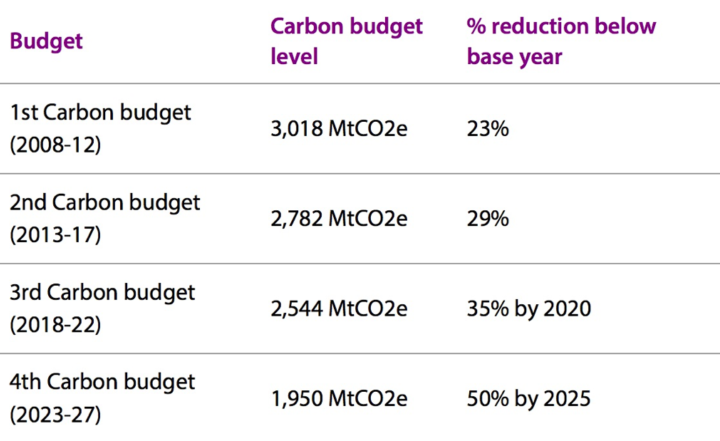

The 57% figure is the fifth Carbon Budget: recommended by the statutory advisor, the Committee on Climate Change, in November 2015, and agreed by the government the following June.

Under the Climate Change Act, successive five-year carbon budgets map out the most economically effective pathway, in the Committee’s judgement, to meeting the long-term legally-binding target of cutting emissions by at least 80% (from 1990 levels) by 2050.

The Act says that ‘as soon as is reasonably practicable’ after setting the carbon budget, ‘the Secretary of State must lay before Parliament a report setting out proposals and policies for meeting the carbon budgets for the current and future budgetary periods’ – setting out policies and the timescales on which they will operate, and explaining how they will ‘affect different sectors of the economy’.

It started life being called the Carbon Plan. It became the Emission Reduction Plan, then the Clean Growth Plan - and now the Clean Growth Strategy.

It can do anything ministers like, up to and including the political equivalent of playing the electric guitar with its teeth. And its title and presentation have been tweaked to fit in with the new departmental priorities of delivering jobs and economic growth from a low-carbon industrial strategy. But if it doesn’t deliver a reasonable level of detail on policies to meet that carbon target, it will have failed in its legal duty.

What is the challenge?

So far, UK greenhouse gas emissions have fallen in line with the first and second carbon budgets, and we’re in line to achieve the 37% reduction for the third as well (the period 2018-22).

These reductions have mainly come from falling energy demand – partly from structural changes in the economy, partly from UK and EU measures that cut energy waste – and from a transition in the electricity sector from coal to gas and renewables.

But those can’t go on for ever. In particular, only about 6% of UK electricity so far this year has come from burning coal, and all of our coal-fired power stations are due to be out of action by 2025.

So, for the period 2028-2032, a raft of new policies will be needed.

Analysis by the Committee on Climate Change (and others) shows the scale of the challenge.

By 2030, the power sector needs to be almost totally decarbonised, with only about 10-20% of electricity coming from gas-fired power stations unless they’re fitted with carbon capture and storage (CCS), which currently none are. So essentially this means an end to gas being used as baseload generation.

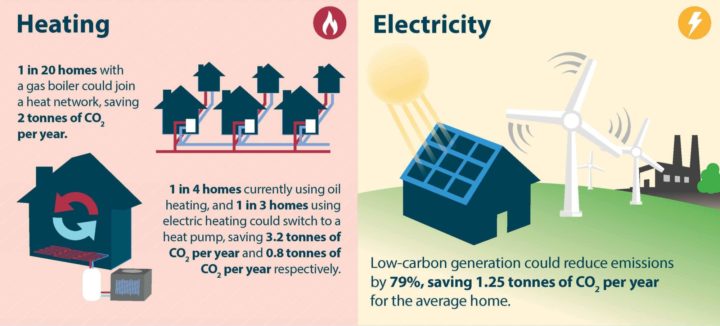

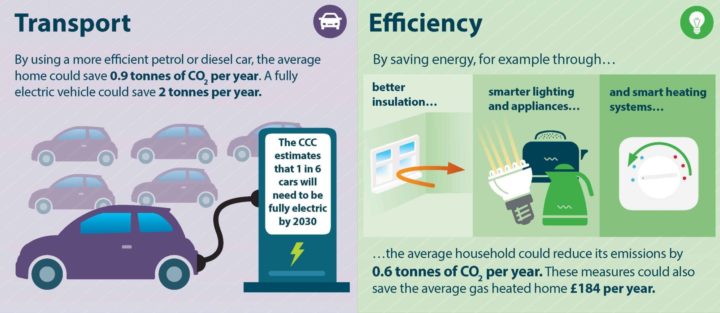

Inroads also need to be made into home heating and transport, and a push on energy efficiency.

The Committee isn’t ultra-prescriptive in saying what has to happen 13 years in the future, but some of its indicative numbers are:

- one in six cars (and two-thirds of new sales) should be electric by 2030

- one in seven homes and one in two businesses should be heated by low-carbon means (such as heat pumps, biomass or solar thermal)

- 3.5 million homes should receive either solid- or cavity-wall insulation between 2020 and 2030.

It’s worth pointing out that many scenarios for meeting the legally-binding 2050 target involve use of CCS. Establishing a fleet of CCS facilities by 2050 really means that building needs to be in train by 2030.

What can we expect?

The indications are that the strategy may be less strategic than many people involved in the clean energy transition would like.

The government has announced today a pot of up to £557m for another round of offshore wind farm auctions. We can also expect that money will be provided for any new nuclear plants beyond Hinkley C that make it to the starting line.

But both of those things would have happened anyway, so can't really be considered part of a new Clean Growth Strategy.

The government is likely to announce £1bn for electric vehicles, mainly to aid rollout of charging infrastructure. The key question is, will this be new money? £600m was pledged in 2009 and much of that has already been spent, so we’ll need clarity on how much of the announced sum is truly new.

There’s very little clarity at this point on low-carbon heat and cutting energy waste. The Conservatives have struggled to develop energy efficiency policy since the Green Deal collapsed in failure. While there are some imaginative ideas out there, such as giving preferential mortgage rates for energy efficient homes, it’s not clear that the government has embraced any of them.

For industry, Climate Change Minister Claire Perry has already trailed the production of seven 'decarbonisation roadmaps' for different sectors, with a large voluntary element thus far.

Possibly the biggest new development is going to be a CCS reboot. It won’t be a restoration of the £1bn fund for developing two commercial-scale projects that George Osborne scrapped in 2015. Indications are it’ll be an order of magnitude less.

How much you can meaningfully do CCS-wise with £100m beyond R&D isn’t immediately obvious – one likely option is to bung the £15 million seed funding it's asking for to the Teeside Collective, a project that if realised would capture and store emissions from power stations and industry, at prices that look reasonably cost-effective.

(Unusual to see a Conservative government funding something with the word ‘Collective’ in the title – but these are unusual times.)

Some more of the CCS money is likely to go on exploring hydrogen manufacture, storage and use – an area in which ministers are said to be ‘interested’. Hydrogen is an option for low-carbon transport; making it during the summer when there’s abundant spare electricity and burning it in the winter to generate electricity is also possible; and it potentially provides a low-carbon solution to heating homes via existing central heating systems. But cost is currently a big obstacle.

‘No regrets’ options

There’s obviously nervousness in the party of the free market about setting policies designed to bring results 13 years in the future. However, there are certain ‘no-regrets’ options that a Clean Growth Strategy could deliver.

One is to ramp up energy efficiency policies, in all sectors. Whatever energy choices are made, using less of it is often the cheapest thing to do. It’s cheaper to do for new buildings than existing ones, so restoring the Zero Carbon Homes policy, bafflingly axed also by George Osborne, ought to be a no-brainer.

A second no-regrets option, for the power sector, is to accelerate rollout of ‘flexibility mechanisms’ – demand switching, storage and interconnection. The National Infrastructure Commission calculates that a flexible low-carbon ‘smart grid’ will cut £8bn per year from our collective energy bill. But flexibility is also cost-effective even with a conventional power system, reducing the cost of grid balancing and enabling more efficient use of baseload electricity.

The draft bill for capping energy prices, also due tomorrow, can help consumers in the short-term. But curbing bills for 2030 means building a smart, efficient system – which will also reduce carbon emissions. Thus progress in these two areas ought logically to lie at the heart of a Clean Growth Strategy.

Likely reception

The last Carbon Plan [pdf], published by the government six years ago in response to the Fourth Carbon Budget, runs to 219 pages and contains significant amounts of detail on sectoral targets and action points.

To be credible, this Strategy needs to go down to the same level of detail, and make clear consistently the twin foci of 2030 and 2050. There’s no reason why it shouldn’t; but the nine-month delay from its original scheduled publication time, and the progressive change of titles ending with the change from ‘Plan’ to ‘Strategy’, have led some to question how specific it’s going to be.

Although lobby groups in various sectors will make their minds known, the most important reaction, given that this is a statutory response, will be that from the Committee on Climate Change.

More than a year in the making, the Clean Growth Strategy is supposed to be the roadmap government will use to keep Britain on track to meeting its climate change targets - at which we have so far been highly successful, leading the G7 in per-capita emission cuts while also leading it in per-capita economic growth.

It’s that important.

Share