(Silk) Road Wars

China and the UK both see growth opportunities in electric vehicles

By Matt Finch

Share

Last updated:

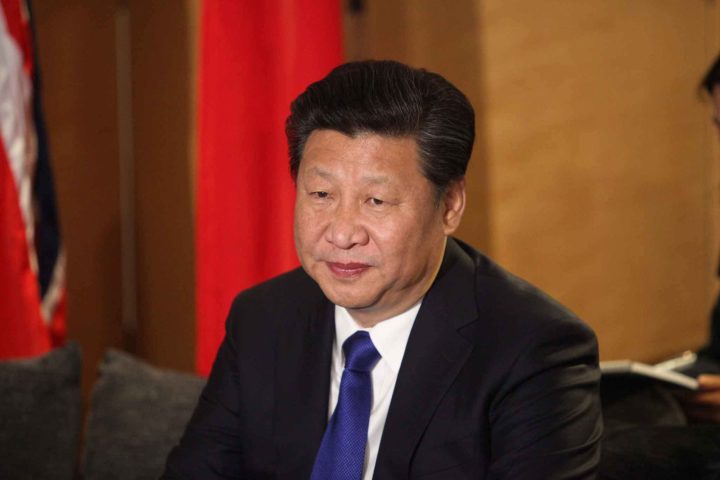

Did you know that (probably) the most important global political event of the year recently finished? No, no, not the Plaid Cymru party conference. Not even the revelation that George Papadopoulos was arrested in America (although that could become the most important event of next year), but the 19th national congress of the Chinese Communist Party.

This once-every-five-year event sets out the upcoming priorities for the Chinese Government, and in case anyone was in any doubt before, it is very committed to expanding on its climate change policies (references to the environment happened 89 times in President Xi’s main speech, compared to only 70 references to the economy).

Whilst some would love to say that combatting climate change is being done for purely altruistic reasons, there is a growing recognition worldwide that growing your economy into the low-carbon economy is the future of, well, the economy. And this is the case in both China and the UK. Indeed, the number-crunchers at PWC estimate that the pair are the current world decarbonisation champions - both nations have reduced the carbon intensity of their economies by over 6% in the past year alone, figures that easily outperform the rest of the G20.

This is backed up by the various explicit plans and policies on offer in both nations. “Made in China 2025” is the (Chinese) Government's policy of trying to create national champions in ten high-tech industries, and the electric vehicle (EV) industry is one of the ten. In effect, it is eyeing up export earnings. And in that sense, comparisons can be made between the UK’s Clean Growth Strategy - our Government’s attempt to grab some export earnings, a cornerstone of which is growing the EV industry.

Sales and manufacturing

China’s absolute EV sales numbers are impressive. In September (last available figures) 59,000 EVs were sold, bringing the total amount sold this year to 338,000. This compares to 7,861 sold in the UK, out of 94,000 ‘alternatively-fuelled’ vehicles sold this year. China will always win the ‘absolute numbers battle’ though, so looking at the percentages is perhaps more instructive, and there the honours are even.

In both countries, EVs are around 2% of sales. Whilst this seems like a very low number, the growth rate of EV sales is very high, meaning in just a couple of years (certainly under ten), EVs will be the major market players (confused as to how this can happen from such a low base? Read this blog from Chris Goodall, who explains the mathematics of this a lot more eloquently than I ever can). The direction of travel is clear though. China explicitly aims to have 5 million EVs on the road by 2020. It will miss that target, but consultancy firm PWC estimate that there will still be 4 million. In the UK, the Committee on Climate Change estimate that 60% of new car sales needs to be electric by 2030 (which would equal roughly 1.6 million new British EVs per year).

But the percentages hide a different story. A whopping 94% of EV sales (so far) in China are of cars that are made in China to wholly-owned Chinese companies (Tesla and BMW make up most of the remaining 6%). The comparative figure for the UK is a big fat zero. The top selling EVs here include the Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV which is made in Japan, and the Nissan Leaf, which is made in Sunderland. Both companies are Japanese, but the ownership of both companies is convoluted - Nissan owns a third of Mitsubishi, whilst Renault owns 43% of Nissan (and in an interesting twist, the French Government owns 20% of Renault). Post-Brexit Britain will, in theory, be able to replicate any Sino-policy, so it’s worth comparing the two countries. Just what could we learn, if anything?

Both countries already offer a subsidy on buying an electric vehicle. In the UK the Government will pay up to £4500 of the asking price, but in China you can get up to Rmb 100,000, which is just over £11,000 (at the time of writing). It also caps the supply of new internal combustion engine (ICE) cars in its major cities (you have to enter a lottery to win the right to buy a new ICE car). So the Government there is squeezing both supply and demand, meaning that for its city-dwelling citizens buying an EV is therefore currently both cheaper and easier than getting a ICE car. This is not true of the UK.

But China is actually phasing out its subsidies, and instead bringing in new cap-and-trade policies on the car suppliers. From 2019, 10% of a company’s new sales have to be electric. If they’re not, it would have to buy ‘credits’ under a cap-and-trade system, or face a very large fine. That 10% becomes 12% in 2020, and you can expect that 12% to be over 20% very soon afterwards. And the credits have to be bought from other car manufacturers (those under the percentage threshold). In short, the message to the car sellers is clear. “Get with the electric programme, or get out our country”. Remember though, when it comes to potential overseas markets, size matters, and every car manufacturer - including the British ones - don’t want to miss out on a share of the world's largest car market.

This cap-and-trade system has a couple of very interesting effects. Firstly, the source of market subsidies shifts from the Government to ICE car manufacturers, and, secondly, it means the domestic EV manufacturers (and Tesla) will be directly subsidised by foreign ICE manufacturers (which itself has the net effect of bringing more money into the Chinese economy). It goes without saying, but there is nothing in the UK policy toolbox that compares to this.

The cap-and-trade percentage will obviously ratchet up to 100% - i.e. a total ban on new sales of ICE cars. The UK has already announced that this will happen here by 2040, but the Chinese have yet to announce a date. The founder of the largest Chinese electric car manufacturer - BYD - reckons that this could be as early as 2030 though.

Other vehicles

Only China subsidises individual sales of electric buses (Rmb 300,000 or just over £34,000), and as a result over 20% of all buses sold there in 2016 were electric. This has resulted in more than 300,000 electric buses already (for comparison, Transport for London has about 2500 hybrid buses). The closest policy the UK has entailed funding being awarded in August for what seems a measly 153 cleaner buses. The Middle Kingdom also has over 200 million electric scooters and motorbikes. For comparison, the UK has 1.3 million motorbikes in total, and the vast majority of those are not electric. In fact, only 162 electric motorbikes and just 3 electric buses were registered in the first half of 2017. In short, China is not just ahead of the UK, but is by far the global leader in the electrification of other road transport modes.

It continues. China has also set a mandatory requirement for government officials that 30% of new public vehicles have to be electric. The UK has no comparative policy.

China has 171,000 charging stations nationwide, compared to 7500 in the UK (although is obviously a far larger country). Beijing (population: 21million, so nearly three times London) plans to install 435,000 chargers before 2020 alone. In contrast, a ‘funding boost’ announced by TFL in August will mean an extra 1500 would be installed before 2020 in London.

It’s not all one-way though. The UK does have policies encouraging the adoption of EVs and the build-out of the charging infrastructure. For instance, the workplace charging scheme means that small businesses and public sector bodies (such as schools) can claim up to £300 per socket back from the government. Vehicle excise duty (road tax to the vast majority of us) is £0 for zero-emission (i.e. not hybrid) cars, whereas the biggest gas-guzzlers will pay £2000 in their first year, although this drops to £450 for the subsequent five years (providing the car originally cost over £40,000). Compared to most countries, these policies stand up well. Compared to some, they are actually very generous. But compared to Chinese policies, they just look a little puny and pathetic.

So what can the UK learn? There are obviously many differences between the two nations. The fact that China is not only the world's largest car market, but also the world's largest centrally planned economy *really* helps. But it’s very clear that the sheer volume of policies is pushing uptake of domestically built EVs in China far more quickly than in the UK, and that the obvious main beneficiaries there are the domestic EV manufacturers. This is reflected in the amounts the respective Governments are spending on their respective EV industries. The UK is already spending hundreds of millions, but one Sino-US think tank estimates China has spent a cool $7.2 billion. So how can the UK replicate these results without resorting to the regulation-heavy deep-pockets approach of the Middle Kingdom? I’ll leave the boffins at BEIS to try and come up with an answer to that. Regardless, the larger question remains: Can, and will, both nations fulfill their aims and turn EV design, development and production into dreamed-of export earnings? It’s too early to tell, but in my humble opinion you should expect BYD to be a household name in the UK relatively soon.

Share