Tilting at windmills: The energy debate down under

Attempts to blame renewable energy for blackouts in Australia have no basis in reality, says Dylan McConnell

By George Smeeton

Share

Last updated:

Battlelines have been firmly drawn in Australia’s power debate, with politicians backing their favoured energy sources like a die-hard footy fan his team.

Against a backdrop of record temperatures, blackouts and high prices for consumers, the greatest casualty has been good policy.

As a breezy sun-baked country with plenty of space, Australia is in many ways the perfect environment for renewable energy. Its steady growth over the past decade in particular has cut deeply into the business model of coal-fired power stations, which have previously been the mainstay of energy generation, but are largely coming to the end of their working lives.

The coal industry is fighting for its existence, and the onslaught against the inevitable advance of renewable energy has been fierce.

Cost and reliability

The main lines of attack on renewables are two-fold: cost and reliability. Neither of these has much basis in reality.

In terms of cost, the fact of the matter is that retail electricity prices in Australia have more than doubled in the last 10 years. Many people are struggling to pay bills, and disconnections have particularly hit the poor.

The rise of renewable energy has frequently been blamed for the increased prices. However, analysis from the Australian National University comparing electricity prices across the states shows this is simply not the case. The ANU study shows absolutely no correlation between increased renewable energy penetration and rising cost.

In fact, Queensland, the state with the highest proportion of coal and gas generation, also faced the highest growth in electricity bills. The state with the lowest increase in bills, Tasmania, also has the lowest levels of thermal power generation.

Of course, price rises are not just related to generation, whether that be coal, gas or renewables. In sparsely populated Australia, network costs - the transmission towers and poles and wires - account for over 50% of bills. To a large extent, the gold-plating of network infrastructure has driven increases in cost.

The current government is pushing hard for investment in so-called ‘clean coal’.

But as my own analysis shows, replacing Australia’s current coal fleet with new Ultra-Super Critical (USC) coal-fired power stations in order to reduce carbon emissions would come at a cost of approximately $62 billion. This would only reduce Australia’s emissions by 27% and would cost more than twice the price of achieving the same result with renewable energy.

Stormy debate

At the heart of the battle is South Australia, which has the highest penetration of renewable energy in the country, and closed its last coal-fired power station in May last year. The debate reached fever pitch when late last year, the state was struck by a giant storm which induced a major blackout.

This was manna for heaven for those who claim that renewable energy is too unreliable.

Once again, the reality was rather different.

The blackout had everything to do with wind - because that’s what blew over the transmission lines. But it had nothing to do with South Australia’s wind turbines or generation mix.

As the Australian Energy Market Operator clearly explained: "there has been unprecedented damage to the network (ie bigger than any other event in Australia), with 20+ steel transmission towers down in the north of the State due to wind damage (between Adelaide and Port Augusta).

"The electricity network was unable to cope with such a sudden and large loss of generation at once. AEMO's advice is that the generation mix (ie renewable or fossil fuel) was not to blame for yesterday's events – it was the loss of 1000 MW of power in such a short space of time as transmission lines fell over.'

A lot of generation capacity was lost because of the transmission failure. Because of that there was a voltage drop and surge across the Heywood interconnector, which connects South Australia with the neighbouring state of Victoria. This is turn triggered safety protection measures that tripped the interconnector and isolated South Australia from Victoria.

Even if the closed coal-power stations had still been operating, they were on the other side of the felled transmission lines and the effects on the system would have been similar. We would still have seen the same cascading failure.

The reality is this could have happened in any state or with any generation technology.

Having initially attempted to lay the blame at the door of renewable energy and the South Australian state government, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull was forced into a backdown after emails released under Freedom of Information rules revealed his own officials had been clearly advised by the market operator that the problem had not been SA's wind power.

Worsening climate

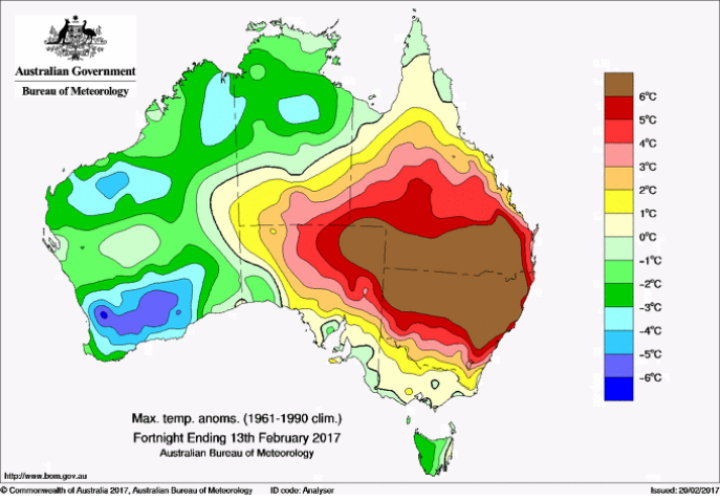

Of course, the great irony is that Australia is also at the forefront of climate impacts including the heatwaves and storms which threaten to destabilise the energy system, such as the one that hit South Australia.

In fact, the coal-heavy state of New South Wales faced a series of rolling blackouts last month as temperatures soared in a heatwave that scientists calculated was twice as likely to occur due to climate change.

We have time to put it right, but dealing with the many complexities of a transitioning energy system requires long-term planning based on honest analysis. Both of these are in short supply today, and Australians are living with the consequences.

Dylan McConnell is a researcher at the Australian-German Climate & Energy College at the University of Melbourne

Share