Blowing down the playing field

Little guys lose out as energy ministers pick winners - but do the numbers stack up?

By Jonny Marshall

Share

Last updated:

With not much going on in the news of late(!), last Thursday saw a flurry of government energy policy documents released into the open, some of which have been a very long time coming.

Alongside announcements from the Carbon Capture Taskforce and details of energy efficiency plans in the ECO-3 era, a couple of documents emerged setting out the future for small scale renewables in the UK – solar panels on rooftops and community-run windfarms, for example.

All of that before this week's big one on big-scale renewables.

While much of the focus in the last few years has been on the precipitous falls in price seen in larger projects, smaller schemes up and down the country produce a substantial amount of electricity each and every year. They also allow members of the public to get involved in the energy transition by installing panels on their homes or chipping into a locally-run low-carbon scheme, helping to boost participation in an industry blighted by disengaged consumers.

Recently, barely a week has gone by without a parliamentarian asking ministers what the future holds for this industry. BEIS oral question sessions have become increasingly repetitive, with the same question ‘what is going to replace the Feed-in-Tariff (FiT) scheme?’ popping up over and over again. The number of bodies and elected officials – from both sides of the house – calling for clarity on the scheme shows the extent to which it has been shut out by ministers - and the concern that exists across politics and around the country.

So, with two consultations now out for response – one on the future of the FiT beyond March 2019 and the other on small scale renewables in general – what is the take-home message? Is it one that builds on Government rhetoric of taking pride in the rate that the UK is decarbonising, backing more low-carbon capacity? Or maybe it’s looking to devolve more power to communities – a long-running Conservative mantra – to let people decide where their energy comes from?

Competition

Far from it. Unfortunately, despite years of talk about levelling playing fields, allowing open competition between technologies and allowing the market to produce a well-rounded generation mix, the latest consultations appear to do exactly the opposite.

Simply put, unless you’re looking to build a monster offshore wind farm or an even-bigger nuclear power plant, you’d struggle to get a low-carbon project off the ground right now.

Which brings us to an oft-stated ambition of government policy - to allow competition to provide the best generation mix.

Unfortunately, competing over a single form of support somewhat hinders the chance of smaller scale schemes coming through. The Contracts for Difference (DfD) scheme was designed with big centralised projects in mind; therefore – unsurprisingly – it generally delivers big centralised projects.

Relying on just a couple of forms of low-carbon electricity generation will also exclude the UK from many of the benefits of diversification (worth £billions per year), and render it more vulnerable to shocks akin to the ‘Beast from the East’ which caused a few sweaty palms in National Grid HQ back in early March (largely a result of the UK’s addiction to natural gas).

This is one thing that nearly everyone in the industry agrees on, be they in nuclear, wind, gas or solar; resilience comes from having a range of sources of electricity.

Questions, questions

Which makes this week’s ‘announcement’ on offshore wind even more confusing. The pot of funding - £557 million - dates from the era when George Osborne ran the Treasury. For all the fanfare, there were really only two new ingredients in Monday's announcement - opening the pot to onshore wind projects on remote islands, and setting out the schedule that will see auctions held every two years until 2030.

However... the announcement, including the schedule, does raise a number of intriguing questions.

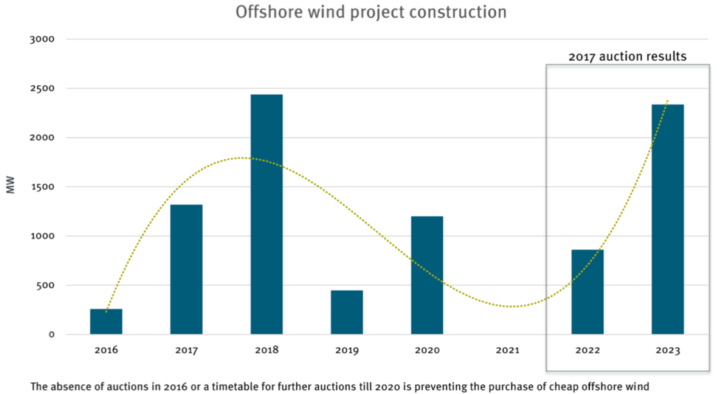

One is whether the pot of money is enough to deliver the volume of offshore wind that the government projects. If the cost of new offshore wind hovers around the £57.50 per Megawatt-hour (MWh) mark achieved in last year's auctions, this funding would deliver just shy of 11GW of new capacity. In addition to the 7GW already operating and the 7GW in the pipeline, this would lead to a total of 25GW installed - well short of the 30GW total ministers are aiming for. The Green Alliance think-tank calculated last year that an additional £250 million might be needed to hit the capacity target.

The renewable energy business has of course proven even its own forecasters wrong time and again, and it is quite possible that if iterative development doesn't bring big new price cuts, radical changes such as floating turbines could. Aurora Energy Research has also proposed opening up other revenue streams such as grid balancing services to wind farms, potentially reducing the sums needed to be paid through CfDs.

Even a steady price of £57.50 would take us into interesting territory. Last September, when those pioneering contracts were announced, we showed that this entailed a net subsidy of just £4/MWh relative to the cost of gas generation. Since then, the price of gas imported into Europe has risen by 34% - and analysts expect the price elevation to remain. So logically, new offshore wind farms at £57.50 would be subsidy-free.

And if that is the case - why limit their deployment? Consumers pay for CfDs through their bills - and every MWh of electricity from a wind farm that we pay for is 1MWh less of electricity from a gas-fired power station that we have to pay for. Constricting the pot will, logically, add to our electricity bills, as well as constricting the path towards carbon targets. If offshore wind power costs do fall significantly, the question will become even more pertinent.

It could take us past another symbolic milestone. If the 16GW build figure is achieved, and if we assume that solar power capacity doubles from its present level - which is possible, although at the moment prospects for solar expansion are really hard to predict - and if we assume that demand stays around its current level, that would take us to the point where variable renewable energy (VRE - wind and solar) provides more than half of our electricity. Symbolic because some hold a view that it can't be done without the collapse of the electricity system and perhaps even civilisation itself.

Missed opportunity?

The one glaring gap in the electricity policy landscape is, of course, onshore wind. Rumours have been swirling - gently, but still - that rehabilitation of onshore wind, at least in Scotland, is on the way.

Announcing that this week would have justified the Cabinet travelling half the length of the nation for its meeting and a real media fanfare - signifying, as it would have, that ministers are not only serious about delivering the lowest-cost electricity they can, but also that they have started putting the needs and desires of the vast majority of Britons above the 2% of the population that strongly opposes onshore wind.

As it is, re-announcing (yet again) the Osborne-era £557m of support for low-carbon power – welcome though the additional clarity on auctioning scheduling will be - does rather suggest that old embedded beliefs are proving hard to cast off. But we must be coming to the point now where re-announcing a 28-month old pot of money no longer qualifies as news.

All the arguments for getting the onshore industry back on track have been made countless times - as they have been for rebooting energy efficiency policy. On both, with recess beginning, we will now have to wait until September before finding out whether rationale becomes reality.

Luckily, politics will be even quieter then.

Share