COP24: Saudi Arabia takes off its trousers

Oil state's lack of 'welcome' heralds the beginning of the endgame

By Richard Black

Share

Last updated:

Generally, even nations most threatened by climate change policy at least try to make it look as though they're onside with the global community and supportive of the science.

Which is what makes the statements of Saudi Arabia at this year's UN climate summit (COP24) all the more illuminating.

And their significance has, I think, generally been missed by civil society groups, in their understandable race to condemn the Saudis for deciding not to 'welcome' the recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

You'll remember that report from October, I think. Not least its most striking conclusion: that if governments want to have a fighting chance of fulfilling their Paris Agreement pledge of trying to keep global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, they need to halve global carbon emissions by 2030.

Imagine your way into Saudi Arabia's position. Your economy is, largely, an oil and gas company. These commodities provide 40% of your GDP and nearly 90% of government revenues. And you're supposed to 'welcome' a report presenting a science-based case for halving this - possibly more than halving it - in the next 12 years?

Really?

In reality, the fact that Saudi Arabia and its neighbour Kuwait found common cause with Russia and the US in downgrading 'welcome' to 'note' in the COP24 agreement speaks volumes about the importance of the report.

In a nutshell, it shows they recognise that it marks the beginning of the fossil fuel endgame.

The Saudis didn't refuse to welcome the report because they don't believe the science is right.

They did so because they know it is.

An honest assessment

Until October, it was possible to argue that restraining climate change was compatible with an oil and gas industry whose longevity was measured in decades.

The IPCC's Fifth Assessment Report in 2013-14 made clear that keeping global warming below the then-international target of 2ºC meant bringing carbon emissions to global net zero 'in the second half of the century' - and in the 2015 Paris Agreement, all governments, including the Saudis, promised to do just that.

That language is so vague, though, that although it has led to shareholder resolutions and divestment, an oil company executive could justifiably shrug shoulders and argue that guaranteed a steady profit stream for the foreseeable future.

Not so the 1.5ºC special report and its proposed target of net zero by 2050. That implies oil use beginning to fall significantly maybe within five years, certainly within 10.

Technologies are here that could make this a reality, and so are some corporate commitments - with Maersk, the world's biggest shipping company, promising to be off fossil fuels by 2050, and VW the latest car giant to commit to ending the internal combustion engine era. Not to mention the huge commitments from China, for example, to roll out electric cars by the million, and from countries such as Sweden, New Zealand, Portugal and the UK which are either committed already or soon will be to national net zero trajectories.

So Saudi Arabia's decision not to 'welcome' the IPCC's report is honest. The report is a threat to the national interest. Why would they?

World's oiliest violin

The Saudis' discomfiture can be seen in the preposterous defence they mounted of their decision - an absolute U-turn, given that as a member of the IPCC the Saudi government had accepted it back in October.

'We didn't have enough time to scan the new draft submitted just before the IPCC's meeting,' bleated lead negotiator Ayman Shasly in an interview with CarbonBrief's Leo Hickman - an excuse entirely devoid of credibility to anyone familiar with the IPCC process and the size and technical expertise of the Saudi delegation.

Meanwhile, he argued, the IPCC did not propose allocating more of the carbon emissions 'allowed' under a pathway to 1.5ºC to developing countries.

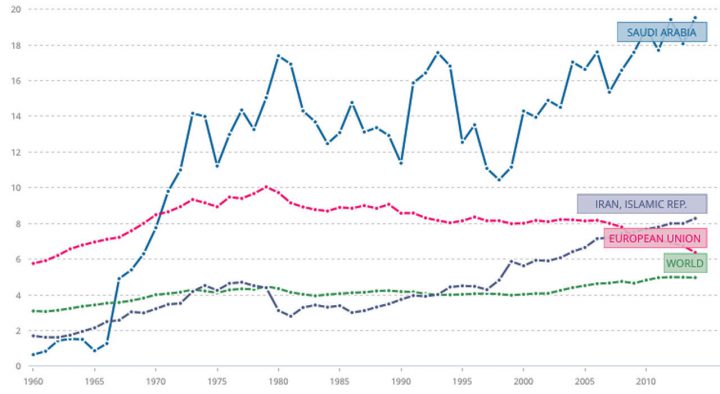

Well - ignoring the fact that the IPCC usually shies away from such things, let's look at some of the stats here. Saudi Arabia's per-capita emissions of carbon dioxide stand at about 20 tonnes per person. That's more than twice the Iranian figure. But I didn't see Mr Shasly suggesting Saudi Arabia should therefore, on the basis of equity, cut its emissions (and perhaps its oil and gas output) more sharply than Iran.

Even more strikingly, Saudi per-capita emissions are more than three times higher than those in the EU, which stand at 6 tonnes per person. Sure, some European countries have stacked up higher cumulative emissions. But not all.

And Saudi per-capita emissions are more than four times larger than the global average.

So - sure, let's have that equity conversation. But let's do it with all the numbers on the table.

A good COP?

Reactions to the COP outcome from scientists, civil society groups and nations keen on climate action have been mixed.

On the one hand there is relief, principally, that virtually all elements of the 'rulebook' - the details of how the various bits of the Paris Agreement are to be implemented - were agreed. This was a vital step forwards, because many aspects of the Agreement could not become reality without a completed rulebook.

On the other, there was concern among some observers that not all elements of the rulebook are as strict as they might have been - and that on one of the most controversial elements of all, the 'trading' of emission cutting measures between nations, agreement proved impossible.

Without strict rules in place, environmental campaigners fear 'double-counting' may become rife, with the same emission-cutting measure being credited to more than one nation.

The other notable feature was that a number of nations and blocs, including the EU, Argentina, Mexico and Canada, said they would increase the scale of the emission cuts they've so far pledged to their fellow countries. That nations do this is essential if the 'emissions gap' - the yawning divide between countries' collective emission-cutting promises and that needed to deliver the Paris Agreement targets - is to be closed.

Of special interest to Britons will be the bid by the UK government to host the 2020 COP at which these enhanced pledges are due to be confirmed.

Despite the UK's continuing presence in the vanguard of climate change leaders, it's not before hosted such a summit - and 2020 is due to be a big one, not only because it concludes the first 'enhancing ambition' phase but also because it could be the one at which the US either leaves or commits to remain within the UN process.

Ins and outs

The world inside UN climate summits is impossible to divorce from that outside.

So the reality of leaders such as Donald Trump and, now, Jair Bolsonaro undoubtedly helped shape many of the decisions - and not, for many observers, in a good way.

But there is, of course, another reality out there. It consists of the IPCC's 1.5ºC report, the sequence of record-breaking warm years, the plummeting costs of renewable energy, battery storage and electric cars, and - now - signs that climate activists are growing in militancy as the emissions gap widens.

COP24 was never going to be one of the most interesting - how could it be, when agreeing a rulebook was its most important task?

But it's happened, and the important stuff got done on schedule. Most importantly, the world's biggest oil producer showed that it knows the endgame has begun.

Share