Out of the internal energy market – are there any winners?

Could the days of a united energy sector position on Brexit be numbered?

By Jonny Marshall

Share

Last updated:

Considering the potential implications, last week’s European Commission ‘Notice to Stakeholders’ on the UK’s looming withdrawal from the internal energy market (IEM) was released with minimal fanfare. Whilst the energy industry has been virtually united on its desire to remain in the IEM, and thereby continuing to trade freely and on equal terms with other European nations, this document spells out how life may be on the outside.

Running to just four pages, it is the first real sign of what post-Brexit terms the energy sector could find itself on, and it signals the potential for a massive shake up, at least in the electricity industry.

On top of the danger of reducing access to short term balancing markets – which keep overall system costs down – and requiring UK-based entities to register in the EU should they wish to retain access to continental markets, the Notice contains some potentially very strong words on interconnectors; one of the technologies that our government is expecting to make serious contributions to UK power supply in the not-too-distant future.

Spelt out in no uncertain terms is the EC’s desire that, as a Third Country, the UK will be responsible for footing the bill for electricity transmission costs inside the IEM – adding a charge for transporting electrons from power station to interconnector on top of the cost of the electrons themselves. This additional charge could completely shake up the economics of interconnection, slashing the price differential between the UK and connected markets, and thereby reducing the appetite for importing power as a means of keeping bills down.

It is difficult to quantify this extra cost – EU network data is only reported for household and industrial consumers rather than on the ‘wholesale’ level, and the fees will be a complex balance of charges for capacity, energy transmitted and location – but any increase in import costs will only accentuate the difference in electricity costs between the UK and mainland Europe. And although most projects in development have reduced their exposure to market revenues via the cap-and-floor system, any increase in the cost of electricity brought into the UK will be felt, ultimately, in household bills.

Annoying the neighbours

On top of an extra cost, there is the issue of how willing other nations will be to allow the UK unfettered access to electricity networks. In France, our main source of imports at the moment and largest exporter of power in Europe, some costs for running the network are socialised via TURPE legislation – preventing homes in one region paying more than those in a different part of the country, for example. The latest period of this control is only one year old, and therefore may need to be reopened to account for the change in circumstances and landing French officials with a sizeable mountain of paperwork, irking bureaucrats to the extent where exports to the UK could be hit with far-from-favourable terms.

The French controls are also structured (as they are in the UK), to encourage electricity consumption away from peak hours, by charging more for grid access on the coldest and darkest winter evening. This is the time that traders are most likely to move power into the UK, and the time that the system will need it most, therefore presenting another headache for ministers and civil servants looking to imports to keep UK PLC running until the domestic wind and nuclear-heavy system comes to fruition in the next decade or two.

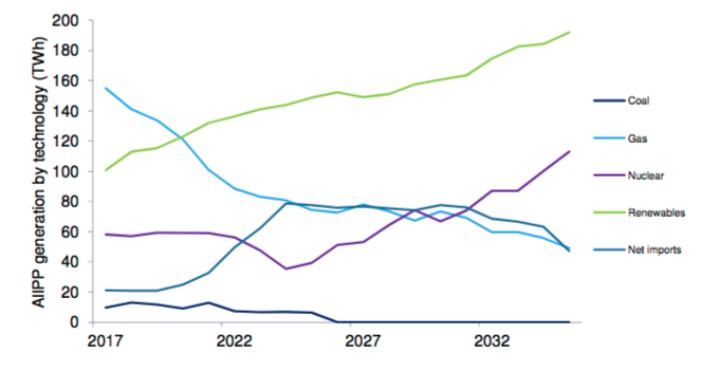

Virtually all reputable forecasts for the UK’s near future see us ramping up power imports in coming years, until the early 2030’s at least, when a massive offshore wind industry could see us shift to a net exporter. On top of new links with France and Belgium, proposed subsea connections to Denmark, Norway and Iceland all feature in future plans to balance renewables-heavy grids across Europe at the lowest cost possible.

Should mountains of paperwork accompany the use of all of these links, the premise of a free-trading, open Britain seems further away than before the referendum. It also risks backsliding into a higher carbon electricity system – one in which new gas plants edged interconnectors in capacity markets, for example – locking in capacity which is incompatible with the current 2030 carbon target, never mind potentially tighter goals which are expected to materialise later in the year.

A united front?

Looking forwards, it will be interesting to see if the energy sector continues its united front on an IEM position. Until now, voices have been in agreement, but actions that could be in the interest of some while stymieing competitors may suddenly find some backers.

Incumbents with a lot of domestic thermal capacity have been lobbying against regulations that they feel unfairly benefit interconnectors for years (of which paying UK transmission charges is one). Should it become apparent that the position outlined in the EC Notice is becoming closer to reality, we may see one or two companies break ranks, should they feel that reduced competitiveness of imported electricity actually works in their favour.

If this does happen, days of the energy sector speaking ‘as one’ on Brexit could be over, with the risk of policies that ultimately reduce competition and boost bills coming to the fore. Compromises and joint positions could be harder to come by, and ultimately, the pace of change in the UK’s electricity sector could slow, with higher bills the unfortunate result.

Share