The pot-holed Road to Zero

Does the Government's long-awaited low emissions transport strategy deliver?

By Matt Finch

Share

Last updated:

Anticipation, excitement, the belief that “this is it”. Finally, it’s arrived. No, not the England football team’s world cup success, but the “Road to Zero” (RTZ) - the Government strategy document that energy and transport nerds alike have been waiting (months) for.

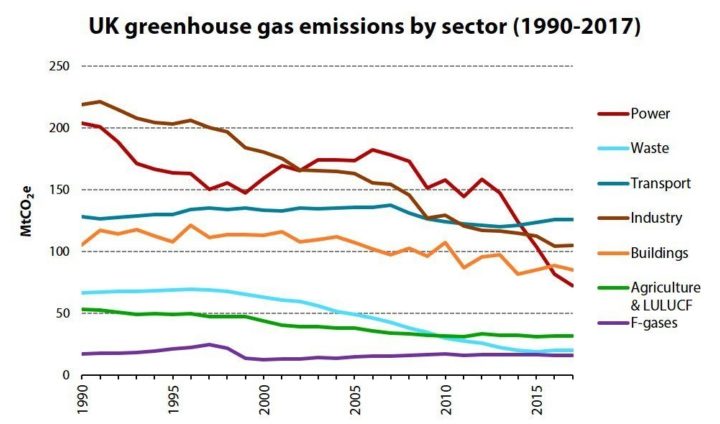

Why is this important? Well, the simple fact is that surface transport now holds the dubious crown of being the sector that emits the most greenhouse gas emissions in the UK.

Of these emissions, cars, vans and HGVs account for almost 90% - which is exactly the area covered in RTZ. Cars alone account for over 50%. In short, this is an important document in the UK's fight to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The UK has made a start though - ‘alternatively fuelled vehicles’ (AFVs) now make up about 5% of new sales every month, although the vast majority of these vehicles have the capacity to burn petrol or diesel. In a zero emission world, most of these cars would not be allowed. Remember, this document is entitled the “Road to Zero”, not ‘Road to somewhere above zero”

So, logically this document should do two things: 1) tell us what the milestones of the road look like; and 2) arrive at a destination where there are zero emissions from road transport in a reasonable timeframe. These are the fundamental requirements of the document. Did it succeed? Well, the short answer is yes, and no.

Timescales

The Government have clearly decided that 2040 is the reasonable timeframe, although it would be remiss not to point out that electric vehicle leaders Norway’s ban on conventional vehicle sales starts in 2025, and India, China, Slovenia, Austria, Israel, Ireland and Holland are all committed to a 2030 ban. Scotland’s ban starts in 2032. Others thought that 2030 was a more appropriate timeframe, including the metro mayors of London, the West Midlands and Manchester. Even the CEO of Shell supports 2030 (and Shell obviously has a lot to lose if cars go electric).

So apart from the lack of ambition on timescales, amazingly, the Road to Zero also leaves the door open to the fact that some new cars will be able to be driven some distance using petrol or diesel in 2040. All new cars will have “significant zero emission capability”. So cars in 2040 will have to be at least a plug-in hybrid - but hybrids have combustion engines in them (again, to contrast internationally, Ireland are banning the sale of new cars with tailpipes from 2030. No wriggle room there at all).

There are specific commitments with specific timeframes in RTZ though. For instance, 100% of central Government’s car fleet will be ultra low emission by 2030, and 50% of new car sales and 40% of new van sales should be ultra low by 2030. It should be noted that these targets are still short of the Committee on Climate Change’s ask for policies that ensure 60% of new vehicle sales are electric by 2030.

Crucially though, the plan has focussed on the near term specifics of charging infrastructure. In fact, this is an excellent near-term ‘tactical’ document for boosting the uptake of electric vehicle charging infrastructure. Reading between the lines, Government clearly believe that get the charging infrastructure right and the rest will flow (as every fan of cheesy 80s films knows, if you build it, they will come. And as every waistcoat-wearing manager knows, get the system right, and the players win). Highlights include a £400m charging infrastructure investment fund that has been set up, a call for all new street lighting columns to include charging points (nothing about retrofitting though), and all new homes to have a chargepoint available. However, the main highlight of RTZ is the simple fact that Government has recognised that regardless of how they get there, many more public chargepoints will be needed in just a few years.

Also recognised is the fact that electric vehicles can have a positive effect on the national grid and electricity demand. One small innocuous line on page 87 could be crucial: “… by 2019 all government supported chargepoint installations will have to have smart functionality”. 2019 is just five months away; effectively the Government has just killed the ‘dumb’ charger market, and really opened up electric vehicles to the power market. Since most home chargers will be bought at the same time as an electric vehicle is bought, and most future electric vehicles have not been bought yet, that is a huge future market right there. In short, expect to see more vehicle-focussed offerings from energy companies (such as OVO Energy’s current V2G trial).

Unanswered questions

RTZ has other aspects to it, including the most blatant implicit attempted ‘automotive market grab’ ever seen in a Government document. (I know, you’re thinking “what is he talking about”? Hear me out).

One major underlying question throughout this document concerns just how affected the UK’s automotive industry - which turns over a cool £77.5 billion - will be in the transition to ultra low transport, and lots of the document is dedicated to what individual companies are doing right now in R&D terms (some of which is funded by Government, and some that is not). Essentially, the major question is just how many of the 814,000 people employed in the sector will have a job at the end of the road? This, however, is the wrong question. Of the 1.7m cars built in the UK in 2017, 1.3m were exported, meaning that these cars had to match the minimum emissions requirements of other countries, not ours. Of the 2.5m new vehicles registered in the UK last year, only 300,000 were built here.

What the Government secretly wants is for British people to buy British cars, whilst still exporting the same volumes (or even more) abroad. So the more pertinent question actually is, how much ‘market grab’ does RTZ prompt? Well, the answer is ‘not a lot’. However, this needs caveating. What RTZ has done is simply rehash an existing policy: there was already an automotive sector deal set out in last November’s Industrial Strategy White Paper, and the question is: is that deal good enough? That is still unknown, and we won’t find out for a few years yet. International context again helps though, with China recently announcing a target of 2m ‘new energy vehicles’ being produced per year by 2020. Luckily, we buy most of our cars from Europe, but we really could all be driving Chinese cars in just a few years.

This document is also very focussed on cars, buses and HGVs. Indeed it specifically welches out of talking about switching to other modes of transport. The simple fact though is that whilst we will obviously need cars for the next decades, we simply don’t need as many of them as there currently are (38m!), and don’t need them to do the number of miles they currently do (253 billion!). Explicitly saying that this should not be part of RTZ really is a cop-out. In the UK, only 3% of commuters cycle to work, compared to 67% who drive (2011 figures).

This matters: Cycle commuters have a 52% lower risk from dying of heart disease, and a 40% lower risk from dying from cancer. Healthier people really help the NHS by simply not using it. Also conspicuously lacking are references to car-sharing and autonomous vehicles (which could radically change the concept of car ownership). There is simply no strategy around this at all in this document. In fact, RTZ explicitly kicks the can down the road when it comes to connectivity and automation, simply promising a call for evidence soon.

In summary, therefore, although the UK rightfully takes pride in being a climate leader, this document does little to boost those credentials. It is a step in the right direction, with some very good policies and statements of intent around increasing charging infrastructure. It’s by no means a leap though. The one thing it is not is a full Road to Zero, but at least it’s not a cul-de-sac. In short, transport is not “coming home”. Let’s just hope something else is.

Share