UK electric vehicle policies: are they destroying the automotive industry?

Hint: nope. Not even close

By Matt Finch

Share

Last updated:

A recent Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) Committee report recently recommended that sales of new petrol and diesel cars should be banned from 2032, in contrast to the current official policy of 2040.

This has resulted in questions from some parts, including this recent Telegraph article, about whether or not the government’s electric vehicle (EV) policies are a good thing or not - with an implicit assumption that EV policies will be bad for the industry.

Since 2032 is only 14 years away, this blog sets out to provide some answers. First, we need to discriminate between two distinct aspects of the situation: what we buy, and what we make.

What we buy

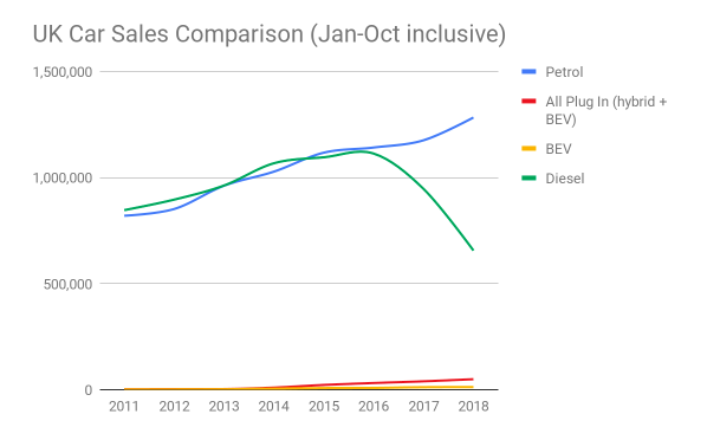

In 2017, Britons bought 2.5m new cars. This was higher than in most of the last few years - but not as many as in 2016. Far and away the largest ‘story’ of recent years has been the decline in diesel sales, as demonstrated by this graph:

You can clearly see the plunge in diesel sales. Clearly UK demand has shifted, and there is no one single reason why this has happened: increased public awareness of air pollution, the VW dieselgate scandal, or a reaction to changes in government policy could, and probably have, all have played a part.

Whether or not this decline bottoms out, or the opposite happens and diesel sales simply die, is yet to be established. What is also clear is that the drop in diesel demand has not been replaced by a corresponding rise in EV sales.

Regardless, the fact is that the UK’s tastes in drivetrains has changed. We’ve stopped liking diesel, and we’re beginning to like electric. Petrol is our out-and-out current favourite though.

What we make

The UK has always manufactured a large number of cars - indeed, the country currently produces the fourth highest amount in the EU, behind Germany, Spain and France. The UK built 1.67m cars in 2017, and this was the second highest amount this century.

Crucially, the vast majority - 80% - of these cars went abroad. In fact, only a third of a million cars were built and sold here in 2017.

And these are specific makes and models. Of the top 10 selling models in 2017, only three were manufactured in the UK (the Nissan Qashqai, with sales of 64,216, the Mini (47,669), and the Vauxhall Astra (49,370). Furthermore, all Jaguars, Land Rovers and Range Rovers are made on Merseyside and in the West Midlands, and they accounted for some 118,000 UK vehicle sales between them (for comparison, JLR sold 614,000 cars worldwide)

Figures for this year so far (up to and including September) show that UK car manufacturing is becoming even more reliant on exports. Compared to 2017, 83,000 fewer cars have been made; but fully 50,000 fewer UK-manufactured cars have been sold in the UK so far - a year-on-year fall of 18.6%.

(NB Almost all ‘British’ manufacturers are foreign-owned. JLR is owned by Indian conglomerate Tata, Vauxhall by German manufacturer Opel (which in turn is owned by Groupe PSA, the parent company of Citroen and Peugeot). Even Bentley, that most British of manufacturers, is owned by Volkswagen. British-built cars owned by British manufacturers are very rare breeds indeed, and include Morgan, Caterham and Mclaren. The UK’s best-selling car - the Ford Fiesta - has not been manufactured in the UK since 2002, although Ford does manufacture engines in this country. Ford is American.)

What becomes very clear is that UK companies are not manufacturing to UK government regulations and policies. The fact is that since exports are the bread and butter of the automotive industry, the cars being built here are being built to other countries’ standards and regulations. If this continues (and, Brexit apart, there is no reason why it should not), future sales are completely reliant on other countries’ future policy framework.

Thus the claim that UK government policies aimed at switching the fleet to low carbon models are damaging the industry are completely incorrect.

Europe and China power ahead

This then begs the question: to whose standards are UK manufacturers adhering at the moment?

The EU accounts for 53.9% of UK car exports, the US 15.7% - and China takes third place with 7.5%. Therefore it is the environmental regulations of these markets to which the UK has to adhere.

Both have regulations to boost EV take-up, and are introducing new ones. The EU Parliament recently voted to impose a fleet-wide CO2 emissions reduction target of 20% by 2025 (from 2020 levels), and an absolute sales target of 20% of a manufacturer's fleet has to be zero / low emission by 2025 (with fines imposed if targets are not met).

Denmark, Ireland and Holland have already announced they will ban sales in new combustion vehicles post-2030. There has even been talk in Germany of implementing a post-2030 ban.

China’s demands for electrification of new vehicle sales are even more stringent. Manufacturers have quotas on numbers of zero-emission vehicles that they have to hit, or pay for credits (which are bought from competitors which overachieve on their targets). This is on top of local laws restricting the purchase of non-EVs in many cities, and direct government subsidies on EV purchases.

Finally, China has announced that it is considering exactly when a full ban on new sales of combustion engines will come into effect (it already has the world’s largest EV market, with over 700,000 sold so far this year).

The trend is clear. In just these two markets - which, remember, were the final destination for fully half the cars the UK made last year (and therefore more than double the number of cars that were both made and sold here) - the intention is to move very quickly towards an electrified fleet.

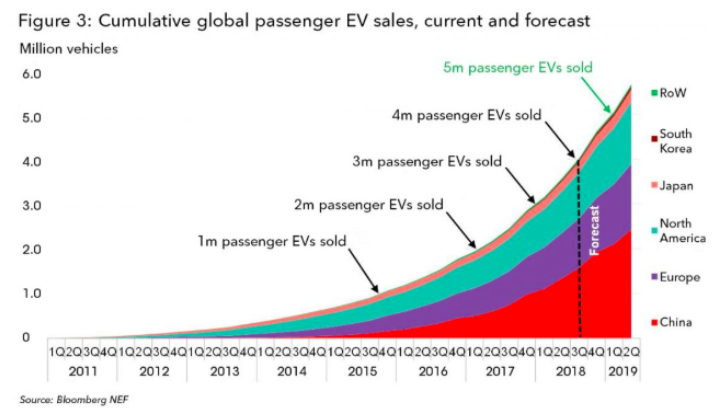

The scale of the transformation is backed up by Bloomberg New Energy Finance predictions about global EV sales:

In short, it is simply wrong to say or imply that specific UK EV policies - including implementing a 2032 ban - will somehow ‘destroy’ the UK’s domestic automotive industry. They won’t. Especially as, and this needs to be stressed:

a) our tastes in drivetrains are shifting anyway

b) the vast majority (over 2 million last year) of the cars we buy - those that actually do have to adhere to UK regulations - are made abroad in the first place.

There is a footnote to this, which seems to have passed venerable Telegraph journalists by.

If all foreign-made cars (Peugeots, Renaults, Citroens, BMWs, Mercedes, Porsches, Volvos, etc) are to be sold here in the UK in a post-Brexit future, they will have to comply with whatever regulations the UK Government imposes.

At the moment, since the UK is a member of the EU, we naturally have the same rules as the EU when it comes to manufacturers emissions regulations. In the future, we may diverge.

Should the UK increase environmental ambition, then some manufacturers may simply decide not to try and sell their polluting products in the UK, which would result in a boost to those that comply. If those ‘complyers’ are based here, this results in a boost to the domestic industry. So there is real potential for a one-off ‘landgrab’, via increased ambition.

Share