Net zero: from ‘tell us’ to ‘show us’

With so much of the world now covered by net zero pledges, it's time to change the focus to delivery

By Richard Black

@_richardblackShare

Last updated:

Saturday’s Climate Ambition Summit saw countries making various kinds of pledge to accelerate emission-cutting: ending use of fossil fuels (Barbados), putting an end to new coal-fired power station building (Pakistan), making deeper reductions over the next decade (Colombia, Rwanda)… and setting a net zero emissions target (Kazakhstan).

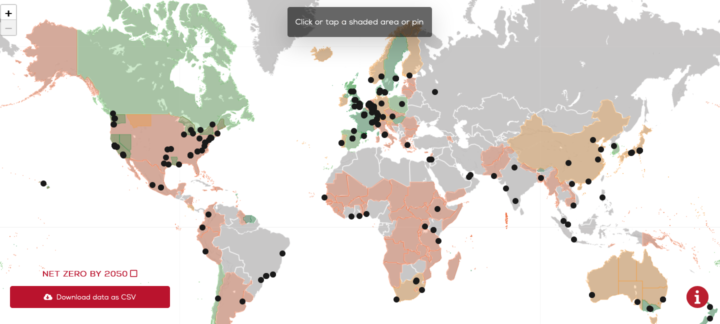

Welcome, Kazakhstan, to the club of net zero nations, states and regions, cities and companies – a club that now has thousands of members, and which is actively recruiting still more, not least through the Race to Zero, launched earlier this year by the UN and the High-Level Champions for COP26.

‘Net zero’ is now such an integral part of the climate change landscape that between two-thirds and four-fifths of global GDP is covered by such targets. That figure might seem a bit vague (more on that later) – but whatever the number, it is certainly a massive shift from the situation just 18 months ago, when ECIU published what we think was the first analysis of the issue. Then, as governments were assembled for the annual ‘intersessional’ meeting of the UN climate convention, the figure was one-sixth of global GDP.

Net zero burst out of its infancy, strode through its teens in a matter of months and is now a respectable, established figure of median age.

Offsetting action

Not everyone is enamoured of the net zero concept. On the eve of Saturday’s summit a group of scientists declared that it is ‘founded on a number of myths,’ and ‘net zero targets several decades into the future shift our focus away from the immediate and unprecedented emission reductions needed.’

The particular focus of their criticism was offsetting, the practice of buying emission credits – usually by implication in a developing nation, and often through planting trees. But other criticisms are also very real:

- A net zero pledge is just that – a pledge – and a pledge doesn’t cut a single tonne of emissions. Unless it is complemented by a plan and concrete measures to get on the path to net zero, how can anyone be confident that the pledge is not just spin?

- Many net zero pledges lack any commitment to reporting progress, or any mechanism by which citizens or (in the case of corporations) shareholders can demand progress

- Many are unclear in exactly what they are promising – whether they refer to all emissions or carbon dioxide only, on the target date, whether they include international aviation and shipping (countries), and which business activities are covered (companies).

The importance of these questions grows with the number of net zero pledges. And when you have as much as four-fifths of the global economy covered, they become extremely important indeed.

The integrity question

For the UK Presidency of COP26, 2020 started with repeated calls for more net zero commitments. If that was a top priority then, it may be less so now: with such a huge slice of global emissions covered by these pledges, there may well be more real emissions cuts to be gained through ensuring all existing pledges are implemented than by securing more pledges.

It is only appropriate for ECIU, then, that as the entity that started tracking net zero pledges, we now turn our attention to assessing the integrity of net zero targets and tracking how that changes.

But this is a huge task; and the tracking of pledges does not look like going away either, with more and more entities, particularly in the corporate sector, showing an active interest.

Oxford University has an interest in this area already, having led the consultation process that led to the ‘starting line criteria’ for entry into the Race to Zero. Hence our decision to join forces for the next phase.

Behind the scenes, supported by a number of colleagues and at times by a small army of student volunteers, we have embarked on the task of categorising the net zero pledges that matter most. To be precise – and in case you think we’re overstating the scale of interest in net zero – the 4,000 that matter most.

Early next year we aim to reveal the first analysis from our collaboration; and while the headline numbers on the share of global emissions, population and GDP look as impressive as you would think, the picture beneath the hood is far from rosy, with a minority of the commitments demonstrating a serious degree of integrity. We believe that going into this detail will promote more informed scrutiny of net zero pledges and, we hope, an improvement in their quality.

In the process we’ll be switching our central GDP measure from ‘nominal’ to ‘purchasing power parity’. It makes a bigger difference to the outcomes than a non-economist might imagine – literally, from around four-fifths of global GDP being covered down to around two-thirds – but PPP is a more accurate measure of the balance of spending power between citizens of various countries, so that’s the measure we’re adopting.

Delivering Paris

Science, through the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), shows us that bringing net carbon dioxide emissions to zero globally around mid-century is key if we are to stand a 50:50 chance of keeping global warming to 1.5°C and so prevent the worst of its impacts. The spate of recent net zero commitments shows that at some level, this is widely understood and that many entities see the value of committing publicly to ‘doing their bit’.

However, far fewer are committed either publicly or privately to the other key part of the IPCC’s 1.5ºC formula: cutting CO2 emissions by 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 (roughly halving them over the coming decade).

The lack of ambition on this measure is not only crucial for climate change, it’s also a logical fallacy – because without substantial emission cuts over the next decade, nations, states, cities and companies will find it far harder to reach their declared net zero targets. Tracking integrity will thus also help those entities making a serious pledge.

As a concept, ‘net zero’ has been a huge success. It’s conceptually simple, it’s caught the imagination of political and business leaders alike, and it’s a necessary part of halting climate change. But so is short-term action; and so is a mechanism to deliver those pledges.

Net zero discourse now has to change from ‘tell us’ to ‘show us’ if confidence in the concept is to be maintained and the Paris Agreement goals to remain realisable.

*Dr Steve Smith is Project Manager of the Greenhouse Gas Removal Project at the Smith School, Oxford University

Dr Tom Hale is Associate Professor in Public Policy at the Blavatnik School of Government, Oxford University

John Lang is Analysis and Communications Officer at ECIU

Richard Black is Director of ECIU

Share