Net zero: why is it necessary?

What's the logic behind a net zero emissions target?

By George Smeeton

Share

Last updated:

A number of countries, including the UK, have made commitments to move to a net zero emissions economy. This is in response to climate science showing that, in order to halt climate change, carbon emissions have to stop; simply reducing them is not sufficient. ‘Net zero’ means that any emissions are balanced by absorbing an equivalent amount from the atmosphere.

In order to meet the Paris Agreement goal to limit average global temperature rises to 1.5°C, global carbon emissions should reach net zero around mid-century. For developing nations, that can mean the 2050s or 2060s; for developed nations such as the UK, it means 2050, or preferably earlier. Many have already set such dates.

The science of ‘carbon budgets’

Climate science is clear that, to a close approximation, the eventual extent of global warming is proportional to the total amount of carbon dioxide that human activities add to the atmosphere.

So, in order to stabilise climate change, CO2 emissions need to fall to zero. The longer it takes to do so, the more the climate will change. Carbon dioxide is just one of the greenhouse gases emitted when we burn fossil fuels; emissions of other greenhouse gases (such as methane, for instance, which has a more intense warming effect in the atmosphere) also need to be constrained.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is clear that limiting temperature rises to a specific level requires net zero greenhouse gas emissions – in other words, deep emissions cuts, and then carbon dioxide removal (technology and nature-based) solutions to absorb remaining emissions.

On the basis of this, the Paris Agreement commits parties to:

“…aim to reach global peaking of greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible, recognizing that peaking will take longer for developing country Parties, and to undertake rapid reductions thereafter in accordance with best available science, so as to achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century.”

This is in order to arrest climate change and limit heating in line with the goal it enshrined: to keep global temperature rises to ‘well below’ 2° Celsius, and ‘make efforts’ to keep it to 1.5ºC.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a report in October 2018 on the 1.5ºC target; it affirmed that global emissions need to reach net zero around mid-century to give a reasonable chance of limiting warming to 1.5ºC.

Since then, the commitment to aiming for 1.5°C was confirmed by the leaders of wealthy countries at meetings of the G7 and the G20 in 2021, as well as by the Glasgow Climate Pact, which was agreed by all parties at COP26 in November 2021. The goal has been reaffirmed by subsequent UN climate summits – COPs – and remains the over-arching goal of global climate action.

Why 'net zero'?

Greenhouse gases:

- carbon dioxide (CO2)

- methane (CH4)

- nitrous oxide (N2O):

- hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs)

- perfluorocarbons (PFCs)

- sulphur hexafluoride (SF6)

- nitrogen trifluoride (NF3)

Converting them collectively to carbon dioxide equivalent ('CO2e') makes it possible to compare them and to determine their individual and total contributions to global temperature rises.

The science has only become clearer and more unequivocal. In 2023 the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report said:

“Limiting human-caused global warming requires net zero CO2 emissions. Cumulative carbon emissions until the time of reaching net zero CO2 emissions and the level of greenhouse gas emission reductions this decade largely determine whether warming can be limited to 1.5°C or 2°C (high confidence) ...

“From a physical science perspective, limiting human-caused global warming to a specific level requires limiting cumulative CO2 emissions, reaching at least net zero CO2 emissions, along with strong reductions in other greenhouse gas emissions. Reaching net zero GHG emissions primarily requires deep reductions in CO2, methane, and other GHG emissions, and implies net negative CO2 emissions.”

In many sectors of the economy, technologies exist that can bring emissions to zero. In electricity, it can be done using renewable and nuclear generation. A transport system that runs on electricity or hydrogen, well-insulated homes and industrial processes based on electricity rather than gas can all help to bring sectoral emissions to absolute zero.

However, in industries such as aviation the technological options are limited; in agriculture too, it is highly unlikely that emissions will be brought to zero. Therefore some emissions from these sectors will likely remain; and in order to offset these, an equivalent amount of CO2 will need to be taken out of the atmosphere – negative emissions. Thus the target becomes ‘net zero’ for the economy as a whole. The term ‘carbon neutrality’ is also used.

Sometimes a net zero target is expressed in terms of greenhouse gas emissions overall, sometimes of CO2 only. The UK Climate Change Act now expresses its net zero emissions target by 2050 in terms of greenhouse gases overall.

Negative emissions

The only greenhouse gas that can easily be absorbed from the atmosphere is carbon dioxide. There are two basic approaches to extracting it: by stimulating nature to absorb more, and by building technology that does the job.

Plants absorb CO2 as they grow, through photosynthesis. Therefore, all other things being equal, having more plants growing, or having plants growing faster, will remove more from the atmosphere. Two of the easiest and most effective approaches for negative emissions, then, are afforestation (planting more forest) and reforestation (replacing forest that has been lost or thinned). Technical options include bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) and direct air capture (see our negative emissions briefing.)

Who is moving to net zero?

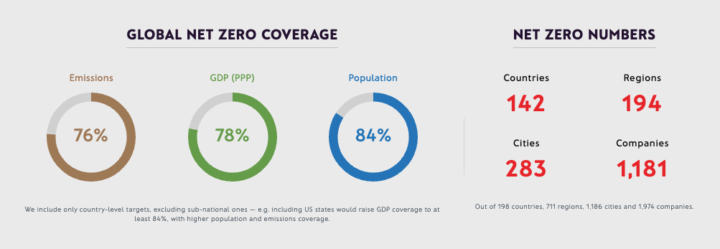

The majority of countries have already set targets, or committed to do so, for reaching net zero emissions on timescales compatible with the Paris Agreement temperature goals. Last year, net zero targets were in place in nations accounting for 93% of global GDP; with the US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement under Trump, but factoring in those US states with their own targets, that number has fallen to 84%. But that still covers three quarters of global emissions, and 84% of the world’s population.

Some of those who committed earliest include the UK, Germany (2045), France, Spain, Norway, Denmark, Switzerland, Portugal, New Zealand, Chile, Costa Rica (2050), Sweden (2045), Iceland, Austria (2040) and Finland (2035). The tiny Himalayan Kingdom of Bhutan and the most forested country on earth, Suriname, are already carbon-negative – they absorb more CO2 than they emit.

In addition, the European Union agreed to enshrine its political commitment to be climate neutral by 2050 in its 2020 European Climate Law. More recently, in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the EU committed to a set of policies to cut emissions by at least 55% by 2030, on the path to net zero, and has recently reaffirmed its aim of 90% emissions cuts by 2040.

The principle that rich nations should lead on climate change is enshrined in the UN climate convention that dates back to 1992, and was reconfirmed in the Paris Agreement. Therefore, when the science says ‘global net zero by mid-century’, there is a strong moral case for developed countries adopting an earlier date.

The UK, France, Sweden, Norway and Denmark were amongst the first to have enshrined their net zero targets in national law. Other nations have followed suit, whilst others plan to legislate. ECIU and Oxford University's net-zero tracker shows the status of all nations' net-zero commitments.

Economic costs and benefits

Putting a price on climate action to deliver the Paris Agreement goals is not straightforward. A 2019 World Bank estimate suggests the necessary global infrastructure investment would cost $90 trillion by 2030. However, the same study also found that the investment will be repaid four times over, whilst a 2018 New Climate Economy analysis suggests bold climate action would, on a conservative estimate, yield a direct economic gain of $26 trillion over ‘business as usual’ by 2030.

In the UK, as recently as 2020, the Climate Change Committee estimated (CCC) that delivering net-zero would cost 1% of UK GDP. In their latest assessment, advising the government on the seventh carbon budget, however, that cost has fallen to just 0.2% of UK GDP. What is more, the investment comes principally from the private sector, and delivers net savings during the seventh carbon budget period (2038 to 2042).

A 2020 Vivid Economics study calculated that the necessary investment would deliver £90bn a year in economic co-benefits (equivalent to 4.5% of 2019 GDP). And an ECIU/CBI Economics analysis in 2025 shows that net zero industries add over £83 billion gross value to the British economy, employ nearly a million people, and – in contrast to the economy as a whole – have grown by 10% year on year.

It has been clear since Nicholas Stern’s landmark 2006 review of the economics of climate change that the costs of not acting are much higher, and estimates have only grown since. In 2021, insurance giant SwissRe calculated that the global economy could lose uo to 18% GDP by 2050, compared to now, if no climate action is taken. That is a level of economic harm greater than both the covid-19 pandemic and the 1920s Great Depression. More recently, a report for the Green Finance Institute showed climate change, nature degradation and other risks, like threats to public health, could lead to a hit to UK GDP of at least 6% by the 2030s, but with the risk of double that in the most severe scenario. And the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries warned at the start of this year that the global GDP loss between 2070 and 2090 could be as high as 50% unless immediate action is taken to address the climate crisis.

In the UK

Immediately after the IPCC published its Special Report on 1.5°C in October 2018, the governments of the UK, Scotland and Wales asked their official advisers, the Committee on Climate Change (CCC), to provide advice on the UK and Devolved Administrations’ long-term targets for greenhouse gas emissions.

The CCC had previously indicated that the UK should be aiming for net zero emissions by 2045-2050. As a wealthy developed nation and one of the largest historic emitters, the UK is expected to achieve net-zero by 2050 at the latest, in order to be compatible with the 1.5ºC Paris Agreement goal.

The CCC delivered its advice in May 2019. Its recommendations were:

- For the UK, a new target: net-zero greenhouse gases by 2050 (up from the existing emissions reductions target of 80% from 1990 levels by 2050);

- For Scotland, a net-zero date of 2045, 'reflecting Scotland’s greater relative capacity to remove emissions than the UK as a whole';

- For Wales, a 95% reduction in greenhouse gases by 2050, reflecting it having 'less opportunity for CO2 storage and relatively high agricultural emissions that are hard to reduce'.

The governments of Wales and Scotland swiftly accepted the CCC's advice, and on 12 June 2019, the UK government laid a statutory instrument to amend the 80% target in the Climate Change Act 2008. Just two weeks later, the new net zero target (100% from 1990 levels by 2050) was formally signed into law.

Only a matter of days before France could complete the feat, the UK had pipped them to it and become the first G7 country to legislate for net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

The Climate Change Committee reports on progress to Parliament each year against that commitment.

Share