Why the UK's 1% of global emissions is a big deal

It's often claimed the UK, at 1% of global emissions, is too small to have an impact, often followed by 'what about China?'. But there's so much wrong with that calculation...

By Gareth Redmond-King

@gredmond76Share

Last updated:

There’s a phenomenon I like to think of as Schrödinger’s Global Britain. It’s where we’re simultaneously a global power with the capacity to lead on the world stage, yet at the same time a mere bit-player which can only do so much. As a position, it works best if you’re keen on talking the talk, without then having to walk the walk.

In climate terms, this is for those who like the idea of hosting global summits, but are not so keen on the climate action they are designed to land. If you want to spot the phenomenon in the wild, just look out for the commentators and politicians who say, ‘oh but the UK only accounts for 1% of annual global emissions; what about China?’

There is so much wrong with that…

Only part of the picture

That 1% only covers the UK’s territorial emissions – those within our borders. But in 2016, the UK’s true carbon footprint was nearly twice that. That is, when you include emissions generated elsewhere in the world either to supply stuff we import, or by things we do outside the UK. That includes our international flights, and imported fossil fuels, as well as things like furniture and consumer goods. After the EU, China is the second biggest source of those goods and emissions, with Russia and the Middle East also in the top six.

Even just at 1% for territorial emissions, we’re still amongst the top emitting countries – number 15 in 2017 and 2018. Actually, nearly a third of global emissions comes from countries whose territorial emissions are each 1% or less of the global total; around half from nations that account for less than 3% each of annual world emissions.

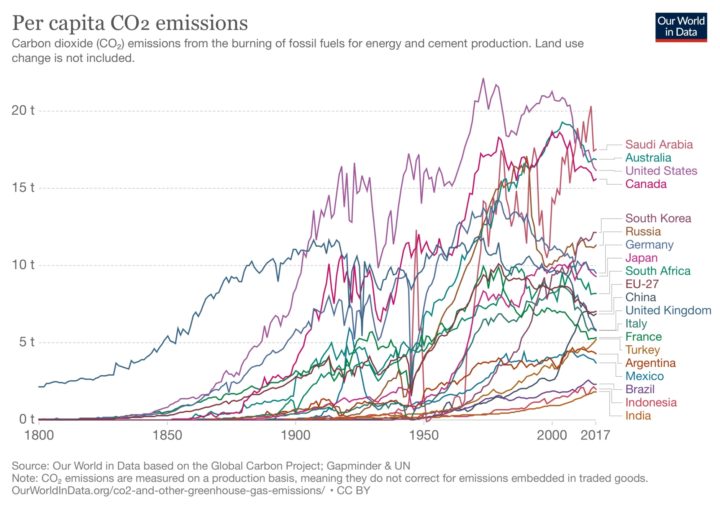

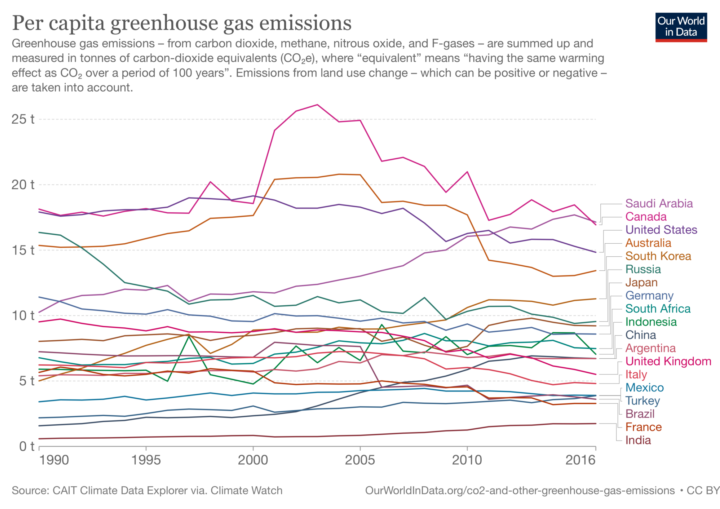

And we creep up the list when you count emissions per capita – i.e. how much we emit per person. Then we’re 13th amongst individual G20 nations (excluding the EU as a bloc) for greenhouse gas emissions; 11th for just CO2 emissions. For contrast, China is middle to bottom half for CO2 and GHGs respectively, and Australia, whose population is 2.5 times smaller than the UK’s, is near the top on both.

History matters

But even if all this wasn’t true, the UK is the fifth biggest historic emitter in the world. That’s because we started the burning of fossil fuels – we were the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution. That’s far from water under the bridge – all those carbon emissions are still up there in the atmosphere, and form part of the climate crisis we face today. This is effectively built in to the UN process, and the Paris Agreement, with greater expectation on wealthy developed countries, not just to cut emissions earlier, but also to provide financial support and assistance to less wealthy, developing countries.

So, if the ‘bit-player Schrödinger’s Global Britain’ is not true, what of the other possibility?

Leading on the world stage

The UK is influential. We’ve been ‘global Britain’ for a long time. We’re a member of the G7 and G20 groups of industrial nations, a permanent member of the UN Security Council, and a founding member of NATO.

When wealthy, powerful nations step up and set emissions targets, others follow. When wealthy, powerful nations step up and commit to the goals of the Paris Agreement, others follow. The UK has led, and others have followed. The UK’s Climate Change Act – putting emissions targets into law – was the first of its kind. More recently, we were the first major global economy to raise that legally-binding target to net-zero, and our level of ambition for this decade (at least 68% cut by 2030 on 1990 levels) is genuinely leading edge.

Leading in markets

Being wealthy, we also have market impact. UK public investment in renewables since 2010 has built a market here that, for offshore wind, is the single biggest in the world. Investment in capacity and supply chain here helped to drive costs down and fuelled technological improvements. That means offshore wind today is cheaper and more effective for every other nation on Earth, because of actions the UK took over the last decade.

And how did we become wealthy? By being at the forefront of not just the first, but also the second and third (electricity and electronics) industrial revolutions. Why would we not want to be at the forefront of the fourth? It undoubtedly includes clean technology, renewables and other climate solutions – so, cleaning up in more ways than one. Not least as our rapid emissions cuts since 1990 have come alongside rapid economic growth.

Going back to ‘the UK only accounts for 1% of annual global emissions; what about China?’ – so, what about China?

China

China led the way, with the US, at COP21 in Paris to help secure the landmark agreement to keep warming to 1.5°C. Recently, they followed other major economies – of which the UK went first – to pledge to achieve net-zero emissions by mid-century; for China the date is 2060. They have committed to peaking emissions by the end of the 2020s (albeit without the short-term plans to deliver that yet), and peaking coal use by 2025. And at this year’s UN General Assembly, Xi Jinping made the huge step of promising to end funding for coal-fired power projects overseas, supporting green and low-carbon energy instead.

China is also a world-leader in solar manufacturing, the single biggest national market for electric vehicles (at 41%), and is not so far behind the UK as one of the biggest markets for offshore wind.

China understands the economic benefits of the net-zero transition, and the vastly greater costs of not acting – including those posed by recently mooted suggestions for carbon border tariffs.

So whilst they have further to go to commit to near-term emissions cuts – ideally ahead of the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow – it is as wrong to characterise them as not acting, as it is to minimise global Britain’s impact as solely being about its percentage of annual global emissions.

Share