COP26 – the Glasgow Climate Pact

The COP26 climate summit has concluded. We take a look at the good, the bad, and the momentum.

By Gareth Redmond-King

@gredmond76Share

Last updated:

Success or failure

After 13 days of talks, the gavel finally came down at the UN climate summit in Glasgow at 11:28pm on Saturday. For COP geeks, that makes it the sixth longest COP – just an hour short of Paris in 2015.

The most asked question about COP26 is: ‘was it a success or a failure?’. I don’t really believe there is a binary answer. It’s why I don’t like sporting analogies that are endlessly used for literally everything non-sporting: because it implies an overall win or overall loss. But it’s not like that.

We’re all losing from the climate crisis and the poorest people in parts of the world most vulnerable to climate impacts are losing far more, and more rapidly than most. We all face greater losses from the climate crisis in the years to come. And even if we keep temperature rises to 1.5°C, those losses are huge.

This process, then, is necessarily about minimising and managing losses, and acting to avert even worse impacts of climate change. On that measure, COP26 in Glasgow leaves us with progress and momentum – and hope that we can yet close the gap to keep warming to 1.5°C. But it also leaves us with anger and disappointment on the part of those already facing losses and damage from climate impacts that wealthy countries are still not doing as much as they need to be doing to cut emissions faster, and to support developing nations.

A picture of complexity

This COP always presented a complex picture. It was not about one deal or outcome, and it was never going to be the last word on getting to 1.5°C. The world came to Glasgow to deal with that complexity and leaves Glasgow with a number of pieces of the jigsaw in place, via the Glasgow Climate Pact.

Real economy signals

COP26 landed various ‘sector deals’ – on coal, deforestation, methane, vehicles, funding for overseas fossil fuels, and getting beyond oil and gas. Some of these shift the dial on emissions and help to keep 1.5° within reach. But they all send powerful signals to move markets, making fossil fuels less economic, and their clean alternatives more attractive to investors.

Added to this is the historic inclusion of language on getting out of coal, and the first reference to fossil fuel subsidies in a UN text since Kyoto in 1997. It started out committing to phase out coal and fossil fuel subsidies and ended up committing to phase down unabated coal power, and phase out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies. But even at that, it adds to signals that should help ensure the demise of coal.

New alliances

Amongst challenging geopolitics, this process helped forge new alliances. In the push on loss and damage, and to focus more on adapting to climate impacts, the nations of the global south have come closer together to work collaboratively to demand support and finance for tackling the emergency they face.

Additionally, one of the tenser global relationships evolved in Glasgow – that between the US and China. As it turned out, their alliance did little to enhance ambition or drive the process in Glasgow forward faster. But it can hold hope that they will help drive momentum together this decade, if they both live up to their individual pledges. And it almost certainly, in a wider geopolitical sense, makes us all a little bit safer than we were before COP26!

Acceleration

The science tells us we are running out of time to keep temperature rises to 1.5°C, and a synthesis of nations’ pledges by Climate Action Tracker shows the world is on track for 2.4°C of warming. So COP26 concluded that it is time to move faster. Rather than waiting another five years to ramp up ambition, the Glasgow Climate Pact calls for nations without Paris-aligned emissions reduction targets to return with net-zero pledges and stronger targets before COP27 in Egypt next year. It also calls for all parties to return in 2023 with higher ambition.

Net-zero has gone global

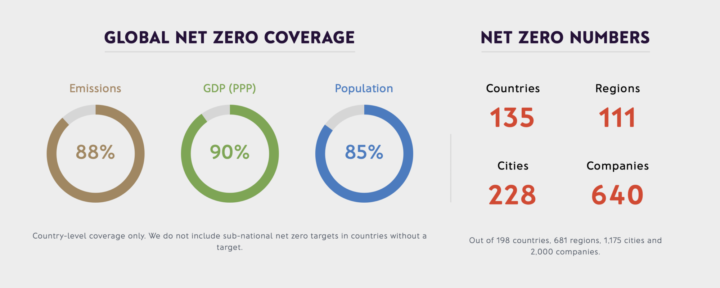

On those ambition targets, it’s worth reminding ourselves that 90% of global GDP and a similar proportion of the world’s emissions are now covered by net-zero targets. Many still lack substance for getting on track this decade, but this a race that everyone is in and there’s no slowing or stopping now.

Supporting the most vulnerable

There are new commitments in the Glasgow Pact that help support the people and nations most vulnerable to climate impacts – enough that developing nations wanted to bank and use them, rather than blocking an overall deal in protest at the considerable amount that was still missing. Finally, a COP has agreed a process for agreeing a global goal on adaptation, as well as committing to doubling adaptation finance. Loss and damage featured in the deal more than it has at previous COPs, including arrangements to operationalise promises made to provide technical and practical advice and support to affected nations.

The biggest gap

But the big gap remains a commitment to establishing finance flows for paying for loss and damage. At COP26, Scotland became the first developed nation to pledge money for loss and damage - £2m. Another sub-state actor, Wallonia, pledged €1m. And philanthropy organisations mobilised to offer $3m to a loss and damage fund, once established. But big wealthy nations, many still lagging on fulfilment of their fair share to the promised $100bn a year in climate finance, refused to agree the necessary language proposed by the G77+China negotiating group of nations.

Instead, there is a process over the next year to develop the loss and damage workstream. Vulnerable nations have sworn to fight to ensure this includes a finance facility when it comes back to COP27. We can therefore expect to see either the founding of such a fund, or a considerable fight in Egypt next year over the issue.

The mechanics

Three areas of the ‘Paris rulebook’ had stubbornly evaded agreement before Glasgow; all are now in place. Five-year common timeframes for nations’ emissions pledges should drive greater ambition than the alternative proposed, which was ten-year spans. Transparency rules have been agreed which seek to prevent nations from cheating in their accounting for and reporting on emissions cuts. And article 6 establishes a market to enable companies and countries to trade carbon credits.

Article 6 has been heavily contested for several COPs. Some nations want to use old credits against new targets, and some believe emissions cuts should count both where they occur, and against the purchaser’s pledges. The deal at Glasgow has avoided the worst loopholes, but is not tight enough to prevent companies and countries who seek to game it. Most unfortunately, especially in the context of the loss and damage gap, the deal prevents any of the proceeds of carbon market trading flowing to poorer nations for adaptation.

Momentum

196 parties to a negotiation will tend towards a messy and imperfect outcome. The COP26 Glasgow Climate Pact is certainly that. But overall, it sends some important signals – that the science is clear, the threat serious, and that this process exists to cut emissions and support the most vulnerable nations.

The world arrived in Glasgow with momentum from Paris, and leaves Glasgow having generated more urgency and momentum than was there before. Globally, public concern is at an all-time high, and people are ahead of politicians in the demands they are making for action to tackle the climate crisis. Of the leaders who have not moved, most of them govern democracies. So they go back now to face their people – their electorates – and answer for not doing what they want. Populations around the world fear climate change and expect leaders to act – not to talk, and then do nothing.

Trashing this COP process – this imperfect and messy process – is a very high-risk strategy. The UN climate process is what has got the world this far, and we have no immediate alternative. We can be sure that the fossil fuel companies and laggard countries reliant on fossil fuel exports would love nothing more than for it to be torn down.

Instead, there are genuine bright spots that generate hope and momentum beyond Glasgow to keep the Paris Agreement goals within reach. Now is the time to seize that hope, set the ambition for the UK’s presidency for the year ahead, and pick up the pace on climate action through to COP27.

Share