Rooting for climate success: the crucial role of trees in net zero

As autumn approaches, it's time to recognise the power of trees and the vital role they can plan in the journey to net zero emission

By Matt Williams

Share

Last updated:

Britain is home to iconic trees and woodlands. From the New Forest in the south of England to remnants of Caledonian forest at Abernethy in Scotland.

Trees hold tremendous powers - from making our lives healthier by cleaning the air we breathe to providing homes to some of our much loved British wildlife.

And their powers don’t stop there. They also play a crucial role in realising the government’s ambition to achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

Trees play a crucial role in net zero

Trees can hold huge amounts of carbon (keeping it out of the atmosphere) and can absorb it from the atmosphere too, compensating for, or ‘offsetting’, some of the emissions released by fossil fuels (although there are concerns that an over-reliance on tree planting could delay genuine climate action).

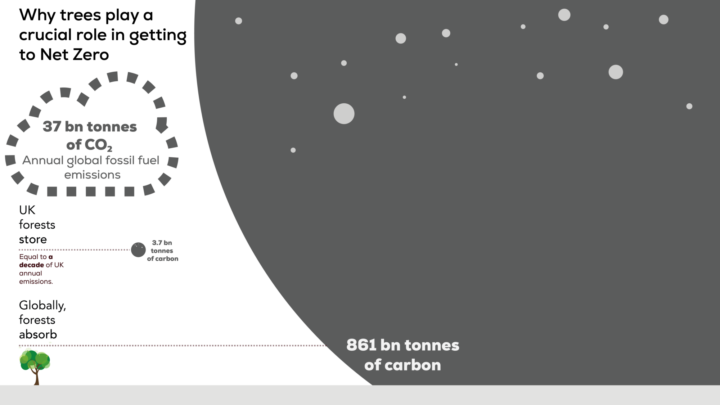

Existing trees and forests are one of the most important stores of carbon on the planet. In the UK, forests hold 3.7 billion tonnes of carbon, or roughly the same as ten years of the UK's annual emissions

In recent years the world's forests have absorbed 7.6 billion tonnes of CO2 every year, 1.5 times the annual emissions of the whole United States. This figure is their overall absorption, minus the emissions they release due to deforestation and other impacts.

The world's forests already hold 861 billion tonnes of carbon. For comparison, the world emits around 37 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide from fossil fuels every year.

Halting deforestation and keeping carbon locked up in trees can limit temperature rises

But, a combination of deliberate logging, and increasingly intense wildfires (the result of heatwaves that are many times more likely due to climate change), mean that trees are being lost worldwide at an alarming rate.

This type of vicious circle leads to feedback effects and even tipping points beyond which forests may permanently lose their ability to store carbon. Sadly, the Amazon rainforest - the largest in the world - has fallen victim to this effect and has transformed from a crucial carbon sink to a net emitter, after decades of deforestation and fires coupled with intensifying climate change.

UK not on track with its tree-planting targets and falling way behind its European neighbours

The general election in late 2019 saw trees become political with parties vying to outdo each other’s tree planting targets. The Conservatives have committed to 30,000 hectares per year across the UK by 2025. There’s a fair gap to close between where we are now and where the Government aims to be.

The Climate Change Committee has advised that UK tree cover may need to climb to as much as 19% by 2050. At present UK tree cover is only 13%. To close the gap between 13% and 19% means planting a new area of trees roughly equivalent to nine times the size of Greater London.

Recent government figures show that just under 2,200 hectares of trees were planted in 2020/21 in England (which is down from 2340 hectares in the previous 12 month period), contributing only 7% of the 30,000 hectare per year goal the Government has set for the UK. This puts the UK, especially England, a long way from the Government’s ambition for planting rates in 2025.

Meanwhile, over the same time period, the Scottish Government planted 10,660 hectares - the equivalent to around 15,000 football pitches, or one third of the 30,000 hectare per year goal.

The UK's tree cover is far lower than most of its neighbours too - at just 13% compared to a European average of 38%.

Investing in trees serves Britain’s national interests

The value of existing woods and trees could be better recognised and protected, including through the planning system. Many of Britain’s most precious woodlands are not in a healthy condition. But properly cared for woodlands and trees can make our air healthier, benefit our mental wellbeing, and slow floodwaters.

More trees will go in the ground if they provide an income for those planting and managing them. Markets that reward the sale of carbon credits can help to do this, as long as there are limits in place - there’s only so much land, and trees need to go in the right place without harming other habitats.

Sellers of these credits need confidence they will be properly rewarded, and buyers need confidence in the integrity of the credits and the benefit they provide to the climate.

Creating supply chains and markets for timber - by encouraging the use of wood in building - will store carbon and generate income for the people managing woodlands. This could also help to create jobs in tree nurseries, woodland management, forestry, sawmills, and construction.

In the 1930s President Roosevelt’s Conservation Corps planted billions of trees and created millions of jobs. The economic boost that accompanies trees, as well as their potential to enhance the beauty of the British countryside, is one of the lowest hanging and juiciest fruits on the way to achieving net zero.