Drought: three ways the UK can adapt to extreme heat

Achieving net zero emissions will help with protecting farmers' crops and families from high bills, and with limiting drought and dry weather.

By Tricia Curmi

Share

Last updated:

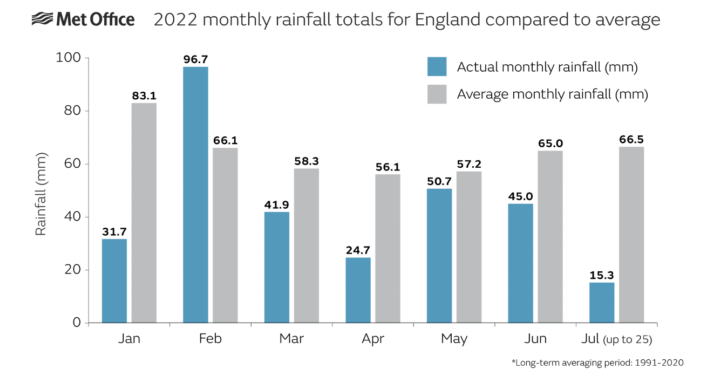

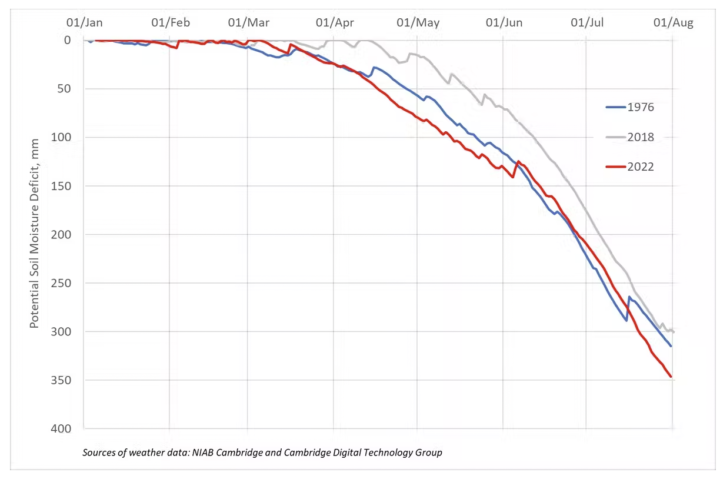

In August 2022 a drought has been declared after the driest start to a year since 1976. But this has been building for months - only two months in the past 12 have seen above average rainfall.

While the effects are dire - from fires to failing crops - this perhaps shouldn't be a surprise. The Met Office have said that drier summers and more drought are what we should expect with climate change. Nor will these conditions be over soon - according to the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, some parts of the country could be in drought until October, or longer, and it could take rainfall events seen once every 5-50 years to end the dry weather. The risk is getting locked into a cycle of dry summers that are only compensated by very wet winters, and the risk of flooding that brings.

Droughts becoming a global issue

The last 12 months have seen only two months with above average rainfall. Some rivers reached their lowest recorded levels for July, and some reached their lowest levels ever. But the 2022 drought isn't confined to the UK - some experts think this will be the driest summer in 500 years for the European continent.

At the root of this lies climate change - the record-breaking temperatures the UK saw in July were made ten times more likely by climate change, according to the World Weather attribution service.

The drought and hot dry weather have posed risks to people's health. But they are also linked to the ongoing cost of living crisis.

Cost of dealing with drought

The worse climate change becomes, the more water companies will have to spend on dealing with droughts and floods. The alternative is to deal with droughts when they happen, but these emergency measures would cost £20 billion more than adapting the water system to climate change. Either way, the worse climate change gets, the bigger this extra bill will be. It is quite possible that these extra costs for dealing with droughts (and floods) could be passed onto consumers through bills.

In the 1976 drought £500 million worth of crops failed and food prices rose 12%. UK food prices have already rocketed before the impacts of this dry weather have been felt. The Government's official drought announcement warned that up to 50% of potato crops could fail, and 10-50% of other vegetables.

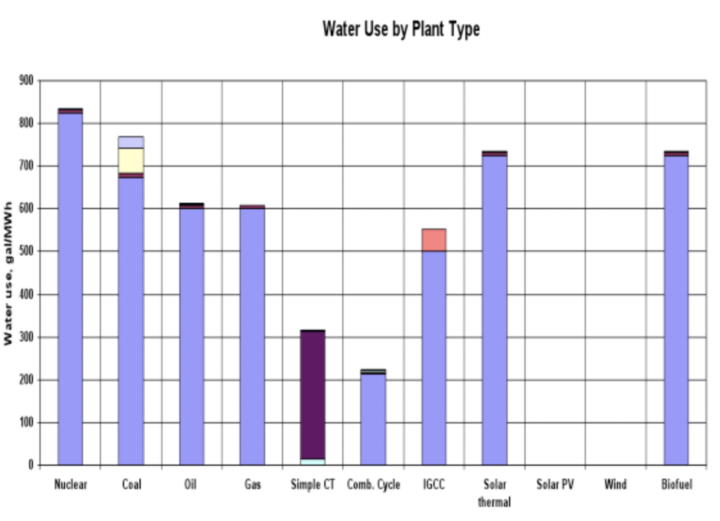

Gas, coal, and oil add water stress

Finally, the energy system still relies heavily on fossil fuel power like gas. These fossil fuels are very expensive - gas is now four times more expensive than renewables and will add £2500 to people's bills this winter - and they are also very water hungry. To make the energy system resilient to future water shortages, and to bring down people's energy bills, the best thing is to replace gas with cheap renewables like wind and solar.

What can be done to adapt our water systems?

To address the water shortages, companies have introduced hosepipe bans, which reduce demand by around 5%. But to deal with the impacts of climate change long-term measures will be needed to help the water system cope.

There are sensible measures that can help to reduce demand and increase supply.

Use water meters

Water meters help to reduce demand by around 15% and thereby reduce bills, but only around half of households currently have them. Even by 2050, water companies' targets are only for 80% of homes to have them.

Address leaks

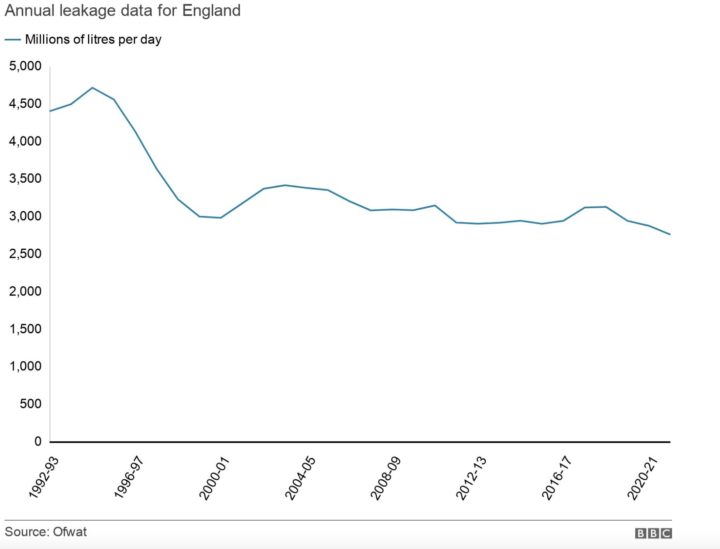

The Public Accounts Committee has said that water companies should address leaks. At the moment around 3 billion litres are lost every day in England and Wales. This is equivalent to 20% of what's used every day (14 billion litres). By 2050 4 billion litres extra will be needed too. So plugging those leaks will be crucial to meeting water demand in years to come. But, water company targets are only to halve leaks by 2050. By 2050 we'll also have 1 billion litres per day less water due to climate change. So we will have less, need more, and still be leaking lots, unless action is taken.

Restore wetlands

The role of farmers and nature is important too. In urban areas wetlands can help to store water, reducing floods and droughts, as well as providing cooling benefits, absorbing carbon, and benefitting people's wellbeing. The way the land is farmed can help to keep more water on it, such as managing soils more sensitively or having more trees and hedges on land to store more water.

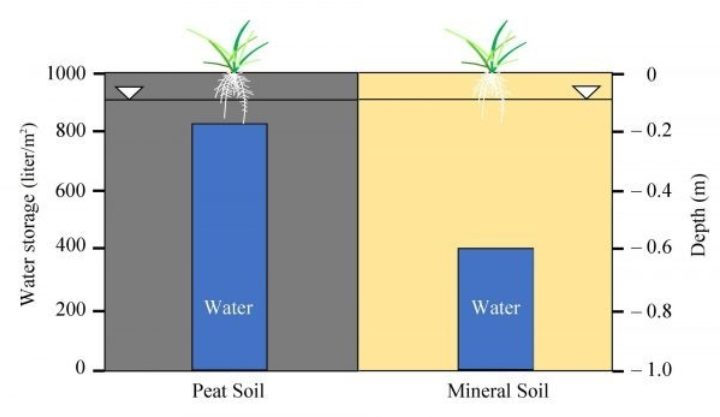

Habitats in the countryside, like peatlands, are amazing water stores. They can hold 20 times their dry weight in water. And when they are in a healthy condition they absorb carbon from the atmosphere, helping to tackle climate change. 70% of UK drinking water comes from catchments dominated by peatlands, so their ability to filter water and improve its quality helps to save water companies a lot of capital expenditure on water treatment. But, around 80% of the UK's peatlands are degraded - restoring them will benefit water and the climate.

Achieving net zero emissions will help with protecting farmers' crops and families from high bills, and with limiting drought and dry weather.