Loss and damage - why we will be hearing these words more

As climate impacts worsen all over the world, we hear of loss and damage more and more. What does it mean, and why will it be so important at COP27?

By Mabeeb Kamalee

Share

Last updated:

With an area the size of the UK underwater in Pakistan, unprecedented floods have killed 1,500 people, and wrought devastation on homes, roads and crops in the country. Pakistan’s Prime Minister, Shehbaz Sharif, in calling for international assistance for his country to recover, made the point that these floods are driven by a climate crisis which Pakistan has had little role in causing.

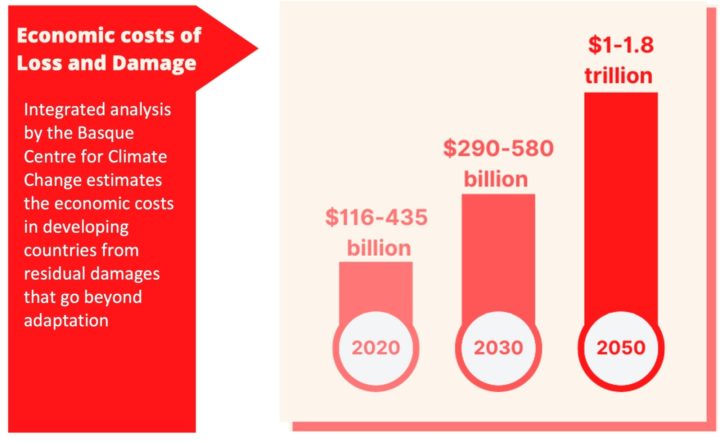

A Christian Aid report published in Glasgow last year showed that, on current trajectories of warming, some of the poorest and most climate vulnerable nations are facing loss and damage costs totalling a fifth of their GDP by 2050; even at 1.5°C of warming, the hit is 13% of GDP

This is why, as we near the next UN climate summit – COP27 in Egypt – we are hearing more and more about climate loss and damage; an issue that remains contentious in climate talks.

These final weeks before COP27 are also the final stages of the UK COP presidency. Time is therefore running out for implementing the Glasgow Climate Pact agreed at COP26 last November. That includes progress on the Glasgow to Sharm El-Sheikh dialogue on loss and damage.

Earlier this year, the second part of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s sixth assessment report was published, detailing climate impacts and the limits of our ability to adapt to them. Showing that almost half the planet’s population is living in circumstances vulnerable to accelerating climate impacts, the IPCC gives momentum to the urgency to act on loss and damage support.

It demonstrated that almost every part of the world has been served up with increasingly stark reminders of what climate impacts look like in practice. Floods, fires and record high temperatures have delivered drought, devastation and huge amounts of damage in rich and poor countries alike, but the costs are felt most by those least able to cope with them.

“Loss refers to things that are lost for ever and cannot be brought back, such as human lives or species loss, while damages refers to things that are damaged, but can be repaired or restored, such as roads or embankments.”

Dr Saleemul Huq, Director, International Centre for Climate Change and Development

What is ‘loss and damage'?

Formally recognised as a term in the 1990s, the United Nation Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) refers to loss and damage as the inevitable impacts of climate change that countries could not reasonably adapt to. This includes permanent losses and damages occurring due to sea level rise, desertification and salinisation causing loss of life, livelihoods, ecosystems or cultural heritage.

It is broken into two separate categories: economic (loss of resources, goods and services commonly traded in markets), and non-economic (including human life, societal and environmental losses). In short, though, it’s about the harm inflicted by the climate crisis – floods, extreme weather, droughts, fires; and the human, infrastructure, natural and economic losses incurred.

Why is it so contentious?

Loss and damage remains one of the more contentious subjects at climate talks. This is because of the question at its heart: who should take responsibility for the loss and damage caused by climate change – nations hit by the affects themselves or those who are responsible for emitting the majority of the greenhouse gases causing the problem?

The logic follows that those who contributed most towards increased greenhouse gas emissions should be the ones footing the bill for impacts hitting the world’s poorest nations. Wealthy nations, however, mindful of the open-ended nature of such a commitment, have cited uncertainty around how liability would be calculated and concern that they could produce ‘unlimited’ claims.

Vulnerable nations have for some time called on richer nations to provide financial assistance that addresses these ongoing, and growing, costs; so far to little avail. A growing body of evidence on the nature, scale and cause of climate impacts, now underpins these calls from the developing nations and small island states on the front line of climate impacts.

Won’t the promised $100bn from wealthier countries help?

In 2009, wealthier developed nations accepted a degree of responsibility for providing support to poorer nations in the form a commitment to provide $100 billion a year by 2020 in climate finance. This funding is to help nations cut their emissions and adapt to climate change, it isn’t for loss and damage – impacts that can’t be adapted to.

Although there has been limited and much delayed progress delivering this commitment, it is often pointed to as resource already being offered, in discussion around loss and damage.

What has been agreed so far?

COP 16 in 2010 first set out work to tackle the issue of loss and damage, emphasising the need for strengthened international cooperation and expertise sharing on assessing risks and determining approaches to addressing them. This was followed by the Bali Action Plan, which raised loss and damage up the international agenda, bringing it formally into negotiations.

The most comprehensive framework, however, came through the establishment of the Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM) for Loss and Damage at the 2013 COP19 in Poland. That was largely focused on technical assistance, capacity-building and risk-management. Since then, loss and damage was included in the Paris Agreement in 2015, and then agreements at COP25 to operationalise the Santiago Network on Loss and Damage in 2019. That built on and developed the aims of the WIM into more practical tools to facilitate co-operation, knowledge-sharing etc, and still fell short of direct financial assistance to address loss and damage.

COP26 and beyond

At COP26 in Glasgow, developing and ‘climate vulnerable’ nations were more organised in working together to frame negotiating demands on loss and damage. The core ‘ask’ was for discussions on a finance facility for loss and damage; in essence, a global fund to assist those hit hardest by climate impacts, and least able to afford the costs, paid for by wealthy countries.

Whilst the issue of loss and damage was more prominent at COP26 than it has been at previous COPs, agreement fell far short, with the Glasgow Climate Pact including a commitment to ‘dialogue’ over the next two years to secure progress on addressing loss and damage. This means a process, outside of the annual COP meetings, for nations, NGOs and other relevant stakeholders to discuss potential arrangements for funding loss and damage costs from climate impacts.

Each year, between COPs, the UNFCCC convenes ‘inter-sessional’ meetings at its headquarters in Bonn, bringing together negotiators and NGOs in discussions to make progress on commitments from the previous COP, ahead of the next. At the inter-sessional meetings in Bonn held under the UK’s Presidency, no progress was made with these dialogues, with discussion still largely focused on technical assistance and support, rather than the finance facility being demanded by the nations most vulnerable to climate change.

Looking to COP27

COP27 is hosted on a continent where some countries are already incurring costs to adapt to climate impacts of between 2% and 9% of their GDP. Other developing nations are facing hits to their GDP in double-figures percentages, even if warming is kept to 1.5°C. Not only will the focus on loss and damage at an African COP be more intense, but expectations will be higher in the face of growing impacts, and growing costs.

For developing countries, a failure to make progress at this COP could damage trust in the UNFCCC process overall. COPs and the negotiations they encompass work when all parties are there as equals, their voices fairly represented in the rooms where conclusions are reached. If the legitimate and growing concerns of developing nations are not addressed in those negotiations, in the interests of wealthy developed nations who prefer to avoid establishing a finance facility for loss and damage, then the talks may start to feel too one-sided on this issue. That could well result in loss of confidence that they are being run on the basis of fairness and equality.

It has now, at least, been agreed that loss and damage will form part of the agenda in Egypt. But many will want to see the work programme established in Glasgow become a standing agenda item – a core part of the COP negotiations and decisions. In Sharm El-Sheikh, developing nations and civil society organisations will look to the Egyptian COP president and the UNFCCC – as well as to other key players like the outgoing UK president – to work to protect that trust, and maintain the integrity of the COP process. That is likely to mean COP27 needing to make genuine progress on loss and damage.

What are the impacts for low-income, low-emissions countries?

Mabeeb Kamalee worked for ECIU on an internship in summer 2022; she is currently completing a degree at SOAS.

Sign up to our Road to Sharm El-Sheikh newsletter to get you up to speed on all the issues ahead of COP27, and then get daily updates from our team on the ground in November.

Share