Heatwaves, wildfires and climate change

In a globalised world, heatwaves and wildfires that would have been impossible, or many times less likely, without climate change threaten more and more of us each year.

By Gareth Redmond-King

@gredmond76Share

Last updated:

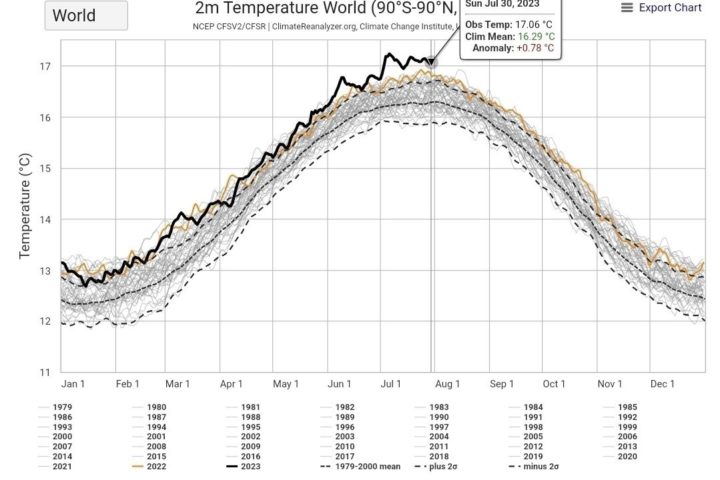

This July – likely the hottest month ever experienced by modern humans – has seen extremes of heat and wildfires blazing across southern Europe, northern Africa, north America, and China. They are wreaking havoc – triggering evacuations, causing deaths, destroying homes and businesses.

It follows the hottest June, a succession of the hottest days ever recorded, hottest sea surface temperatures, and the lowest ever Antarctic sea-ice cover – by some way – as well as extreme storms, floods and other weird weather, like hailstones the size of grapefruit in Italy.

Yet still, on social and in traditional media, there are those who persist with it’s ‘normal,’ what about 1976, and this is ‘just summer – enjoy it’, as well as insisting wildfires are solely the work of arsonists.

Climate caused highs

The heat is severe – with highs of 47°C in Sicily, over 48°C in Sardinia, and over 50°C in Algeria, China and the US – and wildfires tearing across parts of Greece, France, Spain, Croatia, Algeria, Italy, Tunisia, Turkey, and Portugal.

Such extreme temperatures in North America and southern Europe would’ve been virtually impossible without climate change, scientists from the World Weather Attribution (WWA) have found. The highs in China were made 50 times more likely by the 1.2°C of heating humans have caused since industrial times.

Wildfires have made temporary refugees of European holidaymakers. British tourists leaving Rhodes spoke of a terrifying orange hue in the air as they ran from fires and fled the island in small boats. French travellers in Algeria covered their children to protect them from falling ash. The pictures emerging have been hellish. Italy named one heatwave Cerberus after the mythical monster in Dante’s Inferno that guards the gates of hell, and another after the boatman who ferries people to hell.

The WWA report that made clear such scenes would be impossible without human-made climate change also said: “unless the world rapidly stops burning fossil fuels, these events will become even more common and the world will experience heatwaves that are even hotter and longer-lasting”.

Could it be arson?

Greece has been worst hit by wildfires. An average of 50 fires broke out daily for twelve consecutive days in July, according to a government spokesperson. It’s not impossible that all the fires were deliberately started, but this would’ve made it a busy time for arsonists.

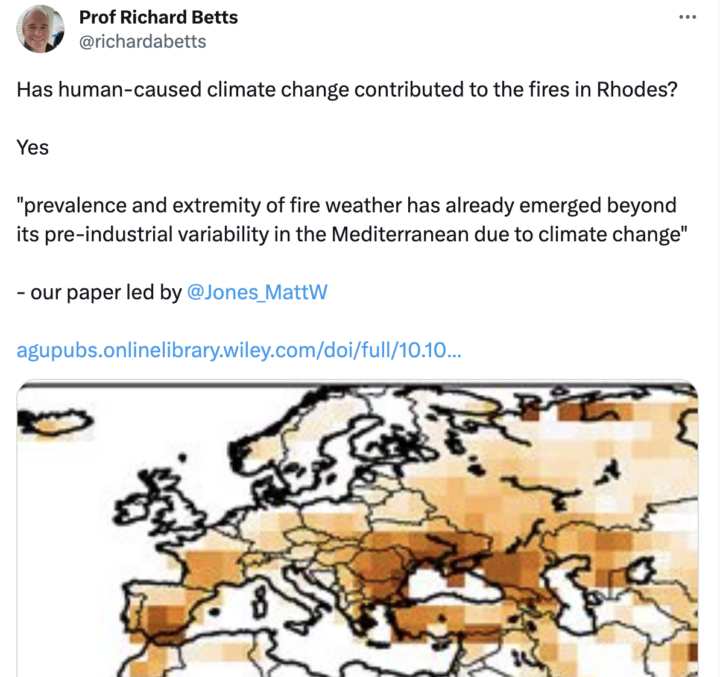

Some on social media are claiming the fires were set on purpose and therefore nothing to do with a warming planet. But, experts say, the source of the fire is beside the point. It’s about condition, not ignition – wildfires only gather pace in certain tinder-dry conditions; conditions created by climate change.

Whether the blaze was sparked by a dropped match, a cigarette not snuffed out properly, an arsonist, or famously a couple of years ago in California from a firework accident at a gender-reveal party, it couldn’t become a wildfire without long periods of dry hot weather. As Nasa explains: “Hot and dry conditions in the atmosphere determine the likelihood of a fire starting, its intensity and the speed at which it spreads.”

Intense heat dries the soil and vegetation, making it highly flammable, and strong winds cause it to spread and become untameable. Since the 1980s, the wildfire season has lengthened across a quarter of the world’s vegetated surface.

Such intense wildfires are likely to become more common as the world warms.

Normal summer?

Extreme heat is engulfing locations across the Northern hemisphere – those in summer – though it is not a normal summer. June 2023 was Earth’s hottest on record; July the hottest month on record.

34 people

were killed by fires that spread across the dry north of Algeria, in northern

Africa, where temperatures reached 50°C in some regions. Forest fires

have been reported across the Middle East in Syria, Tunisia and Jordan, where

temperatures are above 40°C.

Xinjiang in China climbed to 52.2°C. And in Death Valley, in California, the mercury is nudging the hottest temperature ever recorded on Earth, 56.7°C, at around 55°C.

A few have been drawn to the risk of being in such extreme conditions. In Death Valley tourists posed for photographs beside a thermometer reading in the 50s!

What does heat do to the body?

People living in areas affected by insufferable heat may struggle to leave if they’re not evacuated, but tourists choosing to go to these locations, once the extremes have hit, is highly inadvisable.

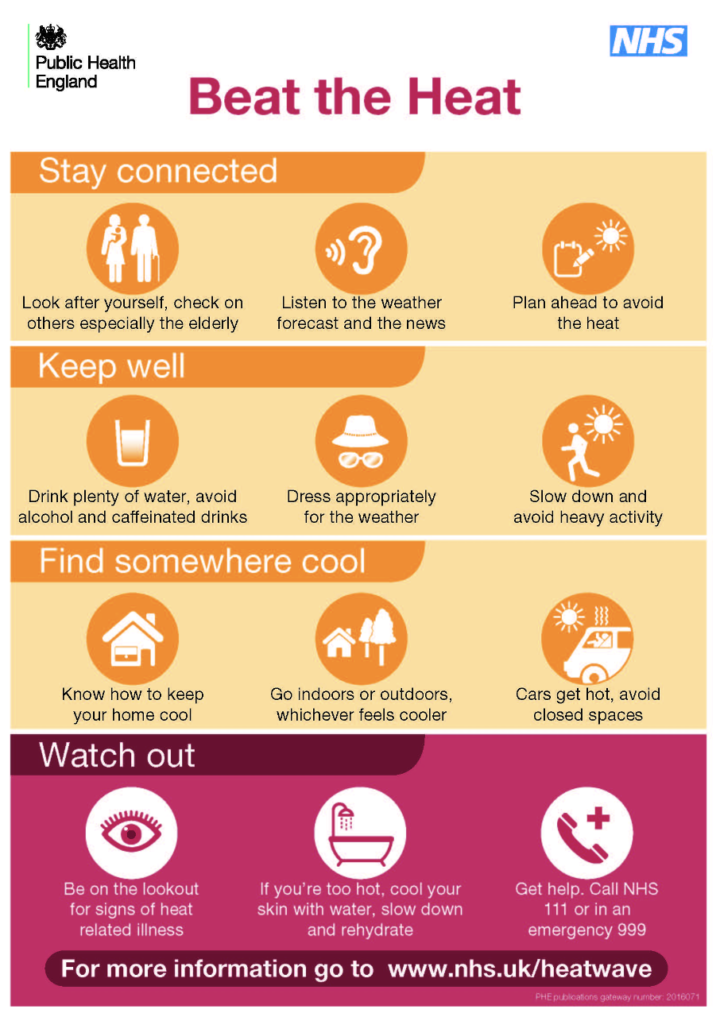

In extreme heat, the body’s systems scramble to regulate, we sweat, the moisture in the sweat evaporates, blood rushes to the surface of the skin and we become flushed. Eventually the body becomes overloaded with heat and can no longer regulate, then the body’s systems go haywire, leading to heatstroke, dizziness, passing out and death.

The NHS has advice on noticing the signs of heat exhaustion and how to cool down.

Europe’s heatwaves of 2022 could have been responsible for 61,000 deaths, nearly 3,500 of which were in the UK. Last year was the deadliest on record for the US, with 1,708 heat-related fatalities.

This year, refugees on the border with Mexico, and workers and the elderly in Arizona and Texas are collapsing and dying in the heat as warm air and high pressure creates a heat dome across the southern states of the US. And 2023 is on track to have the highest number of hiker deaths in America’s national parks.

Heat has become the deadliest kind of weather in the US, with more fatalities than hurricanes and floods.

Not only is heat hazardous, but smoke from wildfires is dangerous when inhaled and small soot particles enter the lungs. Long-term exposure is linked to respiratory and heart problems.

What next?

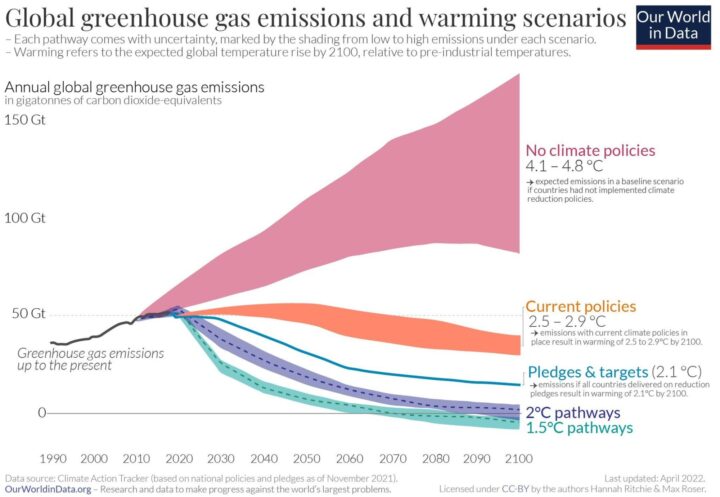

Scientists at the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) delivered a “final warning” in their latest, the sixth assessment report.

A heatwave like those of the last two years would occur every 2-5 years in a world that is 2°C warmer than the preindustrial climate.

As humans continue to burn fossil fuels, emitting greenhouse gases, the world will continue to warm. On current global promises made at the UN on climate, the world is on track for 2.8°C of heating, it currently stands at 1.1°-1.2°C above pre-industrial levels.

The IPCC affirms there is still a chance of staying within 1.5°C. Greenhouse gas emissions would need to peak very soon and then be brought rapidly down. The dangers of warming beyond 1.5°C are clear, we can see the devastation at just 1.1°C.

Net zero emissions by mid-century is the way of avoiding even worse impacts. The IPCC is clear that we have the tools we need – we’re just not acting fast enough. Getting on track means hastening measures like the adoption of heat pumps, electric vehicles and renewable energy such as wind and solar.

Promises to support

The IPCC found nearly half the planet – some 3.6 billion people – were living in areas “highly vulnerable” to climate breakdown. Communities on the frontlines need to be protected from heat, fires, floods, storms and droughts. Wealthy countries have promised $100 billion a year to lower income nations to adapt, recover from disasters and switch to clean energy. So far, this figure has not been met once. Much more will be needed soon.

It is not just a matter of charity. Even though the heat has not been on the UK in summer 2023 – as it was at over 40°C in 2022 – we still feel the effects. Half the food we eat is imported and half of that comes from climate change hotspots. It’s estimated that increased energy prices and climate impacts put more than £400 on food bills in 2022.

That will only intensify as yields of staples fall. Take rice, for instance – extreme floods and heat in Pakistan and India, the two biggest sources of rice imports to the UK, have hit harvests. India has even imposed export limits on some classes. All of which constrains supply and hikes prices.

Increasingly, by protecting these nations, we’re protecting our food supply. And the UK neglects its own self-interests if it doesn’t act on its promises.