Storms, floods, droughts and an unstable food supply

By Tom Lancaster

Share

Last updated:

When Storm Babet tore across Britain, farmer Chris White photographed his waterlogged field in Peterborough and quipped that everyone would be complaining about the price of fish and chips come spring. Potatoes were one of the worst affected crops. But his comment reveals something far graver – how at under 1.2°C of warming, the food we eat is already under threat.

Climate change makes storms more severe and more damaging. Storm Babet brought up to 20cm of rainfall and left hundreds of acres of productive farmland under water. Farmers couldn’t pull crops from the ground nor drill seeds for next year, vegetables and cereals were left to rot. Still reeling from the devastation of Babet, a week later Storm Ciaran lashed the southern half of the UK. The total devastation from the two storms has not yet been calculated.

Farming is on the frontlines of climate change. Almost two thirds (58%) of Britain’s grade one farmland – the most productive and versatile land – is on a floodplain. Without a rapid end to the burning of fossil fuels to avert the worst of climate change and protect the food supply, experts warn of civil unrest.

Drought

Last summer, 2022, England baked under successive heatwaves that sent the mercury over 40°C, a record. It kicked off Britain’s worst period of drought in almost 50 years. Satellite images showed the green and pleasant land had turned a parched yellow.

Farms ran out of water to irrigate crops such as carrots, onions and lettuces. Reservoirs ran dry, soil cracked, crops shrivelled, and farmers pleaded with supermarket bosses to allow wonky and shrunken vegetables onto the shelves. The humble potato sweltered below ground, once temperatures reach 25°C, farmers say it gives up and stops growing. Heat shrank onion yields by 15% and potatoes by 18%.

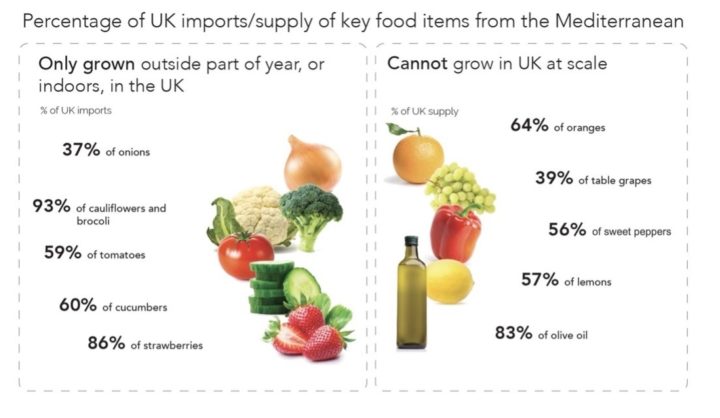

But this was just in the UK. Half of the food Britons eat is imported and half of that comes from the places most vulnerable to climate change. 2022 was the hottest summer on record for Europe, 2023 the hottest globally. A quarter of British food imports come from the Mediterranean, which has been suffering from a cycle of droughts, heatwaves and wildfires.

In Europe, rivers dried up. The Elbe near the northern Czech town of Děčín receded to reveal a hunger carving in stone reading Wenn du mich siehst, dann weine (If you see me, weep). Scientists warned it could be the worst European drought in 500 years.

Drought impacts

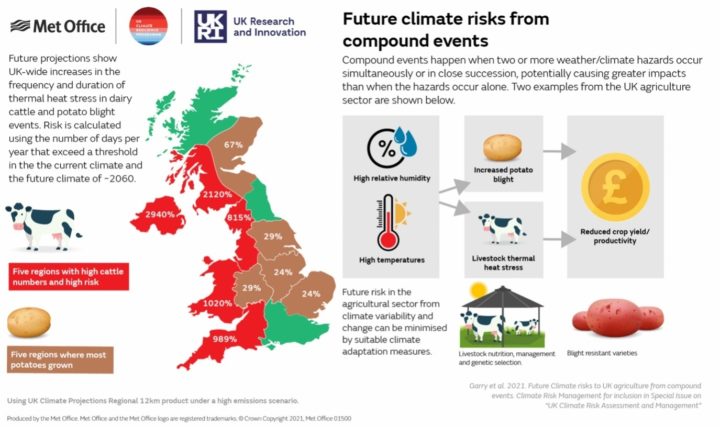

Warmer wetter winters are a feature of climate projections for the UK, as are hotter dryer summers. Drought also changes the nature of the soil, blocking its ability to absorb water, so the rain runs off faster making floods worse. Europe is one of seven regional hotspots where this trend is getting worse and the continent has warmed at twice the rate of the global average.

British shoppers felt the impact of droughts and then floods when they were faced with empty aisles in February. Supermarkets from Glasgow to Dorset had bare shelves after heavy rain in Spain and Morocco disrupted the supply of tomatoes, peppers and other fruit and veg.

Breadbasket regions such as the Mediterranean are often at the forefront of climate change and produce the kinds of foods the UK can’t grow at scale domestically, either at all or for much of the year: cauliflowers, broccoli, strawberries, cucumbers, tomatoes, oranges and lemons.

Shrinking yields

Just three crops – rice, wheat and maize – provide nearly half of the world’s diet. But extreme weather is shrinking rice yields, triggering a crisis. Not enough rain means seedlings can’t grow, too much drowns them, if the sea encroaches, the salt destroys the crop.

India has blocked rice exports to keep dwindled stocks for its own people. In Pakistan, crops were demolished by a flood described by the UN chief Antonio Guterres as a “monsoon on steroids.” And China has charted a steady decline in rice yields over the past 20 years.

Even before India’s export ban, the price of rice surged 11.5%. Asia is home to 90% of the world’s rice production and countries are struggling under extreme heat, parched fields and floods. Rice is a staple for almost half the global population – 3.5 billion people – and poor yields threaten hunger from Senegal to Thailand. Production is predicted to slump by 10% for every 1°C of warming. Meanwhile, the global population grows.

Civil unrest

Without adequate planning to protect the food supply, media warnings of civil unrest could become a feature of British life. Shortages, hunger and soaring prices could lead to clashes, with extreme weather identified as the single biggest threat facing both imports and home produced food.

In the study, 80% of experts said civil unrest in Britain over hunger was possible in the next 50 years. The researchers from Anglia Ruskin University and the University of York also noted that UK farming is designed for efficiency rather than resilience.

Solutions

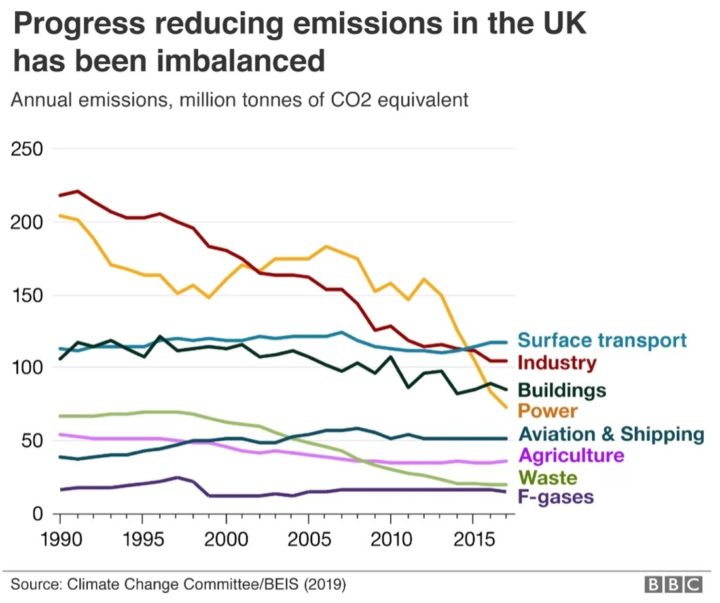

The solution is to avert the worst ravages of climate change by dramatically cutting the use of fossil fuels. But the window for action is closing, the world’s top scientists at the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warn.

Agriculture and food systems are responsible for a third of global greenhouse gas emissions, and 11% in the UK. A third of this global footprint is the methane from livestock farming and waste treatment. Farmers can cut emissions by using natural fertilisers and regenerative farming practises. When farming is designed to maximise output, soil degrades and crops can be more vulnerable to climate impacts. Overhauling the way we farm to focus on long term soil health will make crops more resilient, and can make farmers more profitable whilst maintain yields.

And measures to reduce emissions can have major benefits for food production. Cover crops planted over winter to trap nitrogen and reduce emissions from fertilisers will also restore soil health. These crops are for soil protection, rather than harvesting to sell, and they prevent erosion, nutrient loss and can suppress weeds. Synthetic fertilisers are fossil fuel-based, energy intensive and almost always use natural gas in their production, and by including nitrogen fixing legumes like clovers cover crops can reduce their use.

Other measures set to be supported in Defra’s new environmental land management schemes will also aid resilience. Hedgerows and wood pasture will create shade for livestock, and reduce soil erosion during storms. Wide grass buffer strips along rivers and streams will help reduce the run off associated river pollution during periods of heavy rain. And wildflower margins will boost populations of crop pest predators like ladybirds, ground beetles and assassin bugs that will predate the crop pests predicted to flourish in a warmer climate.

Farms can also use natural flood management such as dams and the restoration of upland peat to lock in water and prevent it flooding both farmland and homes downstream.

Urgent action

Climate change is destabilising the food supply more rapidly than expected, even before the Paris Agreement target of 1.5°C warming is reached. A mixture of water scarcity and outdated, unsustainable farming practises are threatening what we eat, the UN warns. Only a sharp drop in emissions will keep supermarket shelves stocked, and combined with regenerative farming can hugely improve the resilience of farming. The unpalatable truth is that without this, people in Britain could find themselves out of pocket and hungry, with reduce choice and lower quality.