Insulation and gas prices

Households are paying the price for slow progress on insulating homes

By Dr Simon Cran-McGreehin

@SimonCMcGShare

Last updated:

Nine million homes and counting could have been upgraded had support for energy efficiency been maintained over the past decade.

- Improving the energy efficiency of homes is a key part of reducing energy bills and reducing our vulnerability to international fossil fuel markets – key benefits of the move to net zero.

- In 2013, the Government cut support for insulation. Installation rates of insulation fell by around 90%, and successive policies have failed to resurrect the industry.

- The rationale was to cut levies of a few pounds from energy bills, but it was at the expense of forgoing much larger savings in heating homes – particularly with prices set to rise significantly in 2022.

Improving the energy efficiency of homes is a key part of reducing energy bills and reducing our vulnerability to international fossil fuel markets – key benefits of the move to net zero. Insulation is at the core of any home energy upgrade – supplemented by draught exclusion and modern heating controls – and progress was being made, with insulation reaching a zenith of 2.3million installations in 2021.

Then in 2013, the Government cut support for insulation. Installation rates of insulation fell by around 90%, and successive policies have failed to resurrect the industry. Whilst the rationale was to cut levies of a few pounds from energy bills, it was at the expense of forgoing much larger savings in heating homes – particularly with prices set to rise significantly in 2022.

Scope for improvement

UK homes are amongst the least energy efficient in Europe. Using data from Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs), official statistics show that the average rating is band D, where A uses least the energy and G uses the most.

The Government has an ambition to improve this average to band C, a move that would cut heating demand by 20% for each home. That would equate to a 15% cut in our gas imports – which can also be eroded by the move to heat pumps powered by UK-based renewables.

Fabric first

A typical package of improvements to reduce heating demand is based around insulation, as well as draught exclusion – the so-called ‘fabric first’ approach. Two insulation measures in combination (e.g. loft and cavity wall or solid wall) provide well over 10% savings, and towards 20% in some cases, according to analysis for the Climate Change Committee and measurements published by the Government.

Other measures will often be used alongside fabric solutions such as hot water tank insulation and heating controls, but it’s the building’s insulation that’s key and so the low installation rates have been an important blocker of progress.

Such a package of measures built around insulation can be designed to improve a home’s rating from EPC band D to band C, reducing its heating demand by 20% (2,600kWh per year, down from 13,200kWh to 10,600kWh). A similar package of measures applied to homes with a worse EPC rating might not bring them to band C, and might give a lower percentage saving, but could give similar absolute savings (e.g. 2,600kWh per year) and hence the same reduction to the gas bill.

It’s worth noting that insulation is a more cost-effective way to provide long-term help with heating bills than schemes such as the Winter Fuel Allowance or Warm Homes Discount which provide only temporary respite. The Winter Fuel Allowance typically provides £200 a year which would cover 20% of the average band D bill for the year 2021/22, whereas the one-off cost of insulating a home from band D to C would save 20% on every future bill.

Savings on gas bills to-date

Homes without upgraded insulation have been using more energy than necessary, year on year. Looking back over the years since support for upgrades was cut, the average annual gas bill from financial year 2013/14 to 2020/21 is estimated to have been £500 per year, based on Ofgem’s 2019 market report and it’s more recent price cap model – this estimate is probably a little low, but caution is appropriate when combining different datasets.

This average bill is for a gas demand that is close to the average for band D homes. Of this £500, the standing charge is taken to be £100, and unit costs amount to £400, so a 20% reduction in units consumed amounts to a saving of £80 each year.

The average gas bill for 2021/22 rose to an estimated £585 (average of two price caps that started in April 2021 and October 2021), as gas costs began to climb. The full impact of the international gas crisis will be felt in bills in 2022/23, with a forecast average gas bill of £970 under the April 2022 price cap. The methodology behind this data is set out in this ECIU Insight.

Savings on higher future gas bills

The current and forecast bills are illustrated in the following chart for different EPC bands.

Homes in band D typically use 13,200 kWh of gas per year, for which they currently pay around £630 if they’re covered by Ofgem’s October 2021 price cap – £100 more than homes insulated to band C level, which is the level targeted by Government. April 2022’s anticipated price hikes would push up the band D bill by £340, and widen the gap to band C to £170.

This gap can be closed by insulating a band D home to reach band C, permanently reducing its gas demand by 20%, cutting the gas bill from next April by £170 – half of the likely rise for band D.

Source: Ofgem model ‘Default tariff cap level v1.9’, sheet 1b; National Energy Efficiency Data-Framework (NEED) headline tables, sheet 27; and ECIU analysis of gas wholesale prices. VAT at 5% is included in all figures in this analysis, and bills have been rounded to the nearest £10 to avoid spurious precision. Note that cooking accounts for a very small amount of gas and is not considered here.

Also illustrated in the chart is a band F home, amongst the least efficient homes that currently cost £240 more to heat than band C. A band F home is set to cost £420 more to heat from April, widening the gap with band C to £400 – but this could be closed by a strong set of efficiency improvements, cancelling out almost the entire increase in gas prices.

Efficiency improvements are of particular importance for tackling fuel poverty, because households on lower incomes disproportionately occupy homes with worse energy efficiency. This problem of inefficient housing is worst in areas most in need of levelling-up, for example two-thirds of homes in the region of Yorkshire and the Humber fall below the Government’s target for energy efficiency.

In the case of band F homes, for example, 121,000 are occupied by households in fuel poverty, paying excess heating bills £48million a year. And many other households in various EPC bands will struggle with bills when costs rise in April. If the unit rate rises by 60% (i.e. the new rate is 8/5th of the current rate) and other parts of the bill remain roughly static, and a household cannot afford to increase its spending, then it will only be able to pay for 5/8th of the number of units it currently uses, which means cut of 37.5% in the amount of heating (almost 40%).

Slow progress

With these benefits, insulation was being pushed by various Government schemes, and installation rates for (of all types) peaked at 2.33million in 2012. But with the decision to pull the plug, rates plummeted and have averaged around 10% of that rate since 2013.

Furthermore, the cuts to insulation programmes led to job losses and missed creating thousands of jobs in all areas of the UK, and particularly in regions most in need of levelling-up where housing quality is generally lower.

The loss of 2million installations per year from 2013 onwards is equivalent to two installations (e.g. loft insulation and cavity or solid wall insulation) each for 1million homes every year.

So, from 2013 to the end of 2021, a running total of 9million homes have missed out on 18million installations. It’s worth noting that this missed number of installations is close to or below the number of potential installations estimated by the Climate Change Committee (17.5million) and the Government (21million), plus there is scope for installers to expand to into other measures such as floor insulation.

Not all of the potential improvements are in band D homes (of which the UK has an estimated 12million, based on EPC data scaled up to the total of 27million homes. However, a package of measures can be applied to homes with even worse efficiency: this might not get it down to band C (that can take more effort), or even give a 20% cut in its higher energy usage, but the actual energy savings in kWh could be similar to the model we’re considering.

If insulation was being installed at the rate seen in 2012, an extra 250,000 homes could be upgraded from January to the end of March before the price rises kick in. As it is, the major means of progress is ECO, which has installed around 20,000 insulation measures each month on average (mostly loft insulation and wall insulation). So, around 10,000 homes each month could be upgraded with both loft and wall insulation, which is 30,000 over three months.

Mounting penalties

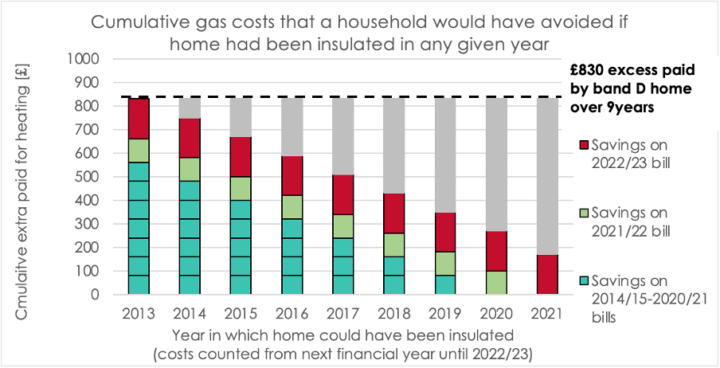

Returning to the figures noted above for the savings achieved by moving from band D to band C, we can work out the cost to households and the country. Each home that was not upgraded in this manner in 2013 has paid the £80 per year for seven financial years (2014/15 to 2020/21) and £100 for the current financial year (2021/22), i.e. a running total of £660 and £830 if we include 2022/23. That’s £830million from 1million homes.

Repeating this process for the million homes that were not insulated in 2014 and so on up to 2021, and then adding together the numbers for each year gives a total of £3.04 billion to the end of March 2022, and an additional £1.53billion for 2022/23. That’s £4.57billion in total to the end of March 2023. These cumulative costs are illustrated in the following chart. (Rounding may introduce a discrepancy of £0.1billion in figures quoted in this analysis.)

Recent analysis by other organisations has reached similar conclusions, but on slightly different basis. Carbon Brief has calculated extra costs of £900million per year under the April 2022 price cap due to the low rates of insulation alone, and costs £2.5bn due to a wider range of policy decisions (effecting industry and households, and equating to £60 for each of the UK’s 27million homes). And E3G calculated that £8billion could be saved annually if all homes rated worse than band C were improved to band C.

Gas crisis could be prompting a rethink

The current gas crisis is focussing minds across Europe on the need to reduce and stabilise energy bills. Countries such as Germany have long histories of making significant progress in cutting households’ heating bills, and countries such as France have had recent success in starting new efficiency drives

In the UK, there have been calls to retain or increase funding for energy efficiency measures. Indeed, a recent UK poll found that more than half of MPs think that the Government is not providing enough financial support for energy efficiency retrofit of homes. Much of the debate is about switching the costs from levies on bills into general taxation, in order to retain the benefits whilst reducing costs for poorer households.