What is climate finance?

With parties at COP29 negotiating a new goal for funding to support poorer, developing nations tackle climate change beyond 2025, we take a look at what is meant by climate finance.

By Edwin Grove, ECIU Intern

Share

Last updated:

The latest UN climate summit, COP29, took place in November 2024. At its core was negotiating a new goal for higher levels of climate finance to support poorer, developing nations to cut emissions and adapt to worsening climate impacts.

With newly-elected UK Ministers heading to Baku for these talks, we take a look at what is meant by climate finance.

Paris and $100 billion

The Paris Agreement is the landmark international treaty on climate change adopted by nearly every nation in 2015. Article 9 says:

“Developed country Parties shall provide financial resources to assist developing country Parties with respect to both mitigation and adaptation”.

This commitment builds on earlier pledges, crucially codifying the promise made at the 2009 Copenhagen Climate Conference by wealthy developed countries to deliver $100 billion a year by 2020, to support climate action in developing countries. The UK played a pivotal role in this; then Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, suggested the $100 billion number, becoming the first major leader to propose a specific financial figure.

Although the OECD reports the promise met, it was at least two years late, stoking mistrust and scepticism from poorer nations. Additionally, Oxfam reports actual support is less than reported, including projects where climate objectives have been overstated. Critically most of the support is in the form of loans – adding to burdens on already highly indebted countries.

UK support and investment in developing nations

In the UK, International Climate Finance (ICF) is the part of the UK’s Official Development Assistance (ODA), to help developing countries respond to the causes and impacts of climate change. ICF is subject to a de facto ring-fence, unaffected by adjustments to the ODA budget, given our commitment to the Paris Agreement. ICF is focused on four key areas:

- helping countries adapt and build resilience to climate impacts;

- pursuing low-carbon economic growth;

- protecting and managing nature sustainably;

- and accelerating the transition to clean energy.

Alongside ODA, further UK investment comes via UK Export Finance (UKEF). This supports UK companies investing abroad, offering loans and loan guarantees, with £2bn of its direct lending capacity earmarked for supporting clean growth projects. It was named the top export credit agency for sustainable financing by trade site, TXF in 2021, and has helped the UK’s development into a major exporter of 'green' goods, accounting for 2.5% of global exports, ranking ninth globally. In the run-up to hosting COP26, the British government pledged UKEF will no longer finance new fossil fuel projects, although it continues to support legacy projects, such as Mozambique’s major Cabo Delgado gas project

UK climate finance - and accounting changes

In 2019 – again, ahead of COP26 – the government made a significant commitment to double its ICF spending to £11.6bn between the financial years of 2021-22 and 2025-26. Towards the end of 2023, however, Ministers announced a broadening of its definition of climate finance, allowing them to count an extra £1.72 billion as ICF. The change of definition means they can reach the £11.6bn target by spending less money than under previous rules. This included classifying 30% of humanitarian aid to climate-vulnerable nations as ICF, even if it had no explicit climate links. Additionally, funds earmarked for multilateral development banks and the British International Investment (BII) institution were reclassified as climate finance.

Even after these adjustments, meeting the target remains challenging; payments have been backloaded, with 55% of the commitment yet to be spent over the next two years.

Fair shares of the $100bn

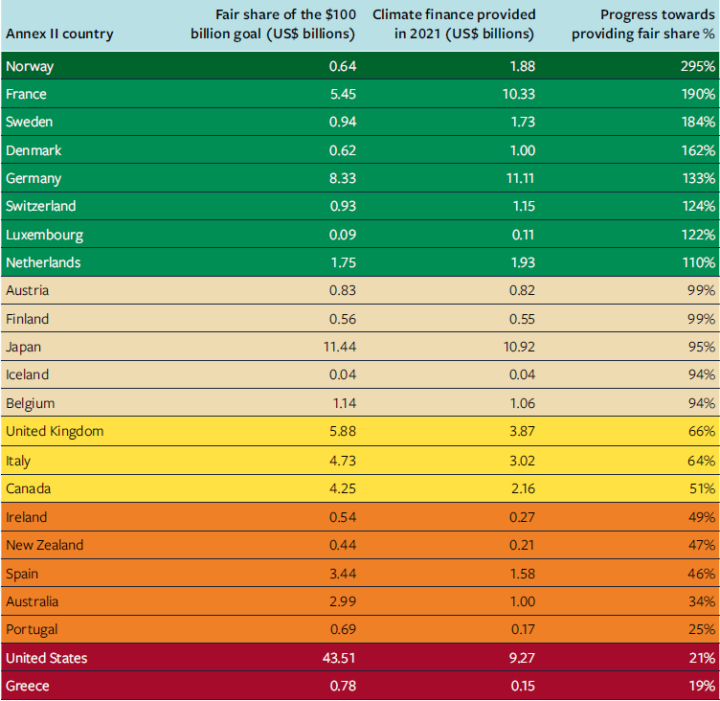

The Overseas Development Institute (ODI) assesses countries' climate finance commitments, with a framework that judges ‘fair share’ based on economic size, cumulative historic emissions, and population. They concluded that the UK’s pledge only accounts for two thirds of its fair share of the $100bn a year. Countries such as Germany, Sweden and France have delivered more than their fair share, with Germany giving $7 billion in 2022.

Climate impacts driving growing costs for developing countries

Developing countries, with their high debt burden, low savings and limited infrastructure are highly vulnerable to climate change. The World Bank projects climate change could push an additional 131.5 million people into poverty by 2030.

Christian Aid reports climate change has already significantly impacted Africa’s economy, with African states’ GDP per capita 13.6% lower than it would have been without global heating between 1991 and 2010. Even if global temperature rise is limited to the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, African nations could face an average GDP hit of 34% by 2100; as high as 64% if current trends continue.

Climate loss and damage

Alongside ICF, in recognition of the disproportionate impacts on lower-income countries of worsening climate impacts, the COP27 climate talks in Egypt established the loss and damage fund. This aims to address the negative consequences of climate change that cannot be mitigated or adapted to; it specifically addresses damages caused by climate change, such as the loss of lives, livelihoods, and cultural heritage.

On average, public debt in poor countries increases by 2.5% in disaster years as spending increases to deal with losses. As average temperatures rise, so climate impacts are worsening in intensity and frequency. So, the costs for poorer nations, most exposed to climate impacts, grow, putting increasing pressure on public finances and jeopardising basic public services.

The UK pledged £60 million to this fund, one of the highest initial contributions, and an important recognition – alongside other G7 nations – of the principle of the responsibility owed by wealthy, developed nations to contribute to climate-related loss and damage. However, the UK’s contribution was repurposed from within the existing £11.6bn and so is not new and additional finance.

Costs and risks of not acting

Nearly two decades ago, the Stern Review established important context for all this: that the benefits of early and strong climate action far outweigh the costs of inaction – a conclusion backed by Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessments.

The economic costs of climate change transcend national borders; emissions, regardless of origin, have a global impact. A 2022 Deloitte report estimates the global economy could lose $178 trillion by 2070 due to climate inaction. The Potsdam institute calculates that, even with mitigation, the world is already committed to $38 trillion in income reduction, and the net benefits of increased mitigation efforts will only emerge after 2050.

Climate change acts as a stress multiplier in poor and vulnerable countries presenting significant risks for global stability, international supply chains, and increasing tensions and likelihood of conflict. The origins of the war in Syria have been linked to climate-induced food and water shortages, for example. The Climate Policy Initiative, considering broader social risks like conflict and migration, therefore suggested the true cost of climate change could reach $1.3 trillion by 2100.

In the UK, we import half our food from overseas. Supporting developing nations to be able to adapt to climate impacts, through ICF, also helps protect the future of those food supplies.

Negotiations at COP29 on climate finance

June 2024 Bonn climate talks were intended to lay the groundwork for COP29 negotiations in Baku, but progress was slow. The new collective quantified goal (NCQG) on climate finance was the main topic as it is mandated to be agreed at COP29. Disagreements persisted over the amount needed, who should provide it, and who should receive it. Unlike the previous $100bn target, the new goal aims to be based on the actual needs of developing countries, which are substantial – and growing.

Developing country groups seek funding of around $1 trillion a year. But wealthy countries refused to discuss a dollar amount. Research by economists Nicholas Stern (author of the 2006 Stern Review) and Vera Songwe in 2022 suggested developing countries collectively need about $2.4 trillion annually to tackle the climate crisis. Of this, about $1.4 trillion could come from domestic budgets, leaving the rest to come from private sources and international bodies like the World Bank. There are also suggestions, including those being discussed within the G20, for novel global forms of taxation – e.g. on financial transactions, frequent flying, and on billionaires. All will be in the mix at negotiations in Azerbaijan.

UK – new government, new climate leadership?

The new Labour government has signalled it wants the UK to reclaim its position as a global leader in climate action. Ed Miliband, Secretary of State for Energy Security and Net Zero, will lead the UK’s negotiating team at COP29 and has already reaffirmed the government's existing £11.6 billion commitment; no new funding has yet been announced for post-2025 commitments.

Miliband's leadership, working with Foreign Secretary David Lammy, is expected to contribute to a foreign policy reset on climate issues, particularly in relation to the Global South and in its relationship with Europe.

Consequences of not delivering

As the UK prepares for COP, the expectation is that all wealthy nations, including the UK, will arrive at Baku with new commitments and plans to scale climate finance from billions to trillions, globally. If they do not, or if talks fail to make enough progress, the risks are great. Not only do developing countries need this finance as a matter of growing urgency, but the issue is also one that goes to the heart of confidence in international negotiations.

If wealthy countries are seen to fail to step up to – or worse, step back from – Paris Agreement obligations to support developing nations, it risks undermining credibility of the COP process. Given the momentum that has been built on clean transition since 2015, and midway through a critical decade for climate action, the consequences of that would be far-reaching.

Share