Brazil and food imports

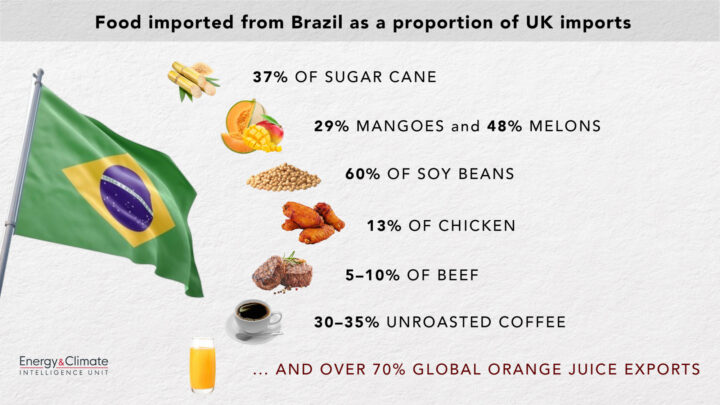

Analysis reveals how vulnerable food imports to the UK from COP30 host Brazil are to climate change, including household staples like coffee, orange juice, chicken and beef, and soy for UK livestock.

Last updated:

Two fifths of the food we consume in the UK is imported from overseas. Most of that is food we cannot readily grow in the UK. Lacking the necessary climate to cultivate tropical fruits, rice, tea, coffee etc, we would need expensive, energy-hungry infrastructure to grow the crops at any kind of industrial scale. Around 15-17% of those imports come from climate vulnerable countries with lowest levels of resilience to worsening climate change impacts.

Brazil, host of the latest UN climate change summit, COP30, tops the list of those countries. Once you remove wealthy, developed and more climate resilient North American and European Union nations from which we import food, in 2024, Brazil was the number one country from which the UK imports food, whether you look by value or volume.

Its agriculture supply chains account for about a quarter of its GDP, and agriculture is the highest-emitting sector in the Brazilian economy, as well as driving deforestation. And Brazil is a country on the frontline of climate change impacts, which pose a direct threat to the size and quality of agricultural yields.

CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACTS

Drought

2023-2024 saw climate change and El Niño combining to inflict severe drought conditions on the Brazilian Amazon; lasting 18 months, it was considered the most intense in the seventy years since monitoring began. 2025 has again brought severe drought to many parts of Brazil with concern growing that an emerging La Niña will raise the risk of drought in crop-growing parts of the country through early 2026.

Heavy rainfall

Southern Brazil, hit by disastrous floods in 2024, has again seen heavy June rains in 2025, hitting crops and livestock in the region. Rainfall in recent years has been made heavier and more intense by climate change, and turbo-charged by El Niño, making the 2024 floods twice as likely.

Extreme heat and fires

On current trends, Brazil is facing around 2.2°C of temperature rise by 2050, with several regions warming faster than the global average. Extreme temperatures hit crops – reducing yield and quality – with a crop like coffee (for which Brazil is the UK’s largest supplier) particularly vulnerable.

Crop failures and resulting food shortages and price increases are a significant risk from these climate change impacts. In 2024, the combination of extreme heat and drought, followed by heavy rainfall and flooding, hit agriculture hard – particularly corn, soy, rice and coffee. Damage to infrastructure hampered logistics of harvesting and transporting food, even when crops were not affected. Reviews of outputs showed declines across multiple crops, with cassava, cocoa, rice and wheat hit hardest.

FOODS

Beyond Europe and North America, Brazil was the UK’s leading food supplier by volume and a major supplier by value, sending around 1.4 billion kilograms (or 1.4 million tonnes) of food worth nearly £1.2 billion last year. This is similar in value to imports from China and the United States but significantly higher in volume, underscoring Brazil’s central role in what ends up on British plates. Some of the foods most affected:

Soy

The UK’s closest connection with Brazil is for soy, which underpins intensive livestock production. In 2024, the UK imported £243 million of Brazilian soy - around 60% of total soy imports. Around 90% of imported soy is used for animal feed. Extreme weather has increasingly disrupted soy production in Brazil. Droughts and heatwaves have affected the Amazon, Cerrado and southern grain belts, with record-low river levels in 2024–25 delaying exports. The 2023 Amazon drought was found to be around 30 times more likely because of human-induced climate change.

Deforestation and climate change are leading to less rainfall, undermining natural cooling systems and damaging agricultural productivity - climate change is projected to reduce soy yields by roughly 6% for every 1°C of warming.

Coffee

Brazil is our largest supplier of green coffee beans, typically providing 30–35% of the UK’s unroasted beans, worth around £225 million in 2024. As the world’s top producer of Arabica, much of the coffee arriving via European partners also originates from Brazil.

Coffee is among the most climate-sensitive crops, with 97% of production occurring in countries highly vulnerable to climate change. In Brazil, hot and dry conditions linked to El Niño reduced expected yields in the 2023/24 harvest, driving price spikes that peaked in March 2025.

Chicken

Chicken is one of the UK’s most valuable direct food imports from Brazil, reflecting its role as a global poultry powerhouse. In 2024, the UK imported £143 million - about 51,000 tonnes - of Brazilian chicken, or 13% of total UK chicken imports, below the 95,370-tonne tariff-free quota agreed post-Brexit.

Brazil’s poultry sector is closely linked to its soy industry, since soymeal is the main protein feed for broilers. This means the environmental consequences of and pressures on soy, namely deforestation, drought and rising temperatures, also affect poultry supply chains.

Beef

Brazil is the world’s second largest beef producer and the largest exporter. Brazil is an important supplier of beef to the UK, accounting for 5–10% of imports in 2024 - around £91 million worth - making it the second-largest source after Ireland. Most export-oriented beef comes from the Amazon and Cerrado biomes. These regions have faced severe droughts and record heat in recent years, worsening pasture stress and water scarcity.

Extensive cattle ranching is the number one culprit of deforestation in virtually every Amazon country, and it accounts for 80% of current deforestation. This deforestation is not only responsible for 3.4% of global emissions each year, but is pushing us close tipping point that could see the Amazonian ecosystem become too dry to sustain itself.

Tropical fruit and sugar

In 2024, the UK imported around £48 million of guavas, mangoes and mangosteens (29% of UK imports), £49 million of fresh melons excluding watermelons (48%), and £36 million of fresh watermelons (29%). Imports of fresh limes were worth £23 million (87%), while fresh papayas totalled £11 million (86%).

Raw cane sugar is another key commodity, with UK imports from Brazil worth around £97 million in 2024, accounting for roughly 37% of total UK sugar imports. These flows of fruit and sugar contribute to year-round food availability and manufacturing supply in the UK while supporting agricultural livelihoods in Brazil.

Brazil’s fruit and sugar exports are increasingly exposed to climate extremes. In recent years, prolonged droughts and record heat have strained crops and water systems across key producing regions, with strong scientific evidence that human-driven climate change has made such events far more likely.

Orange juice

Brazil is the world’s dominant citrus producer, producing roughly one-third of all oranges globally and supplying over 70% of the world’s orange juice exports, largely from the state of São Paulo. Orange juice remains one of the most visible links between UK consumers and Brazilian agriculture, reflecting both countries’ deep trade ties in agri-food commodities.

However, the sector has been hit hard by climate stress and disease pressures. Prolonged droughts, heatwaves and the spread of citrus greening disease have reduced yields and squeezed processing capacity, contributing to higher prices over the past decade.

NB - references and links are in the full report - download at the top of the page.

SOLUTIONS

Cutting emissions

The only solution to halt climate change, and avoid ever worsening climate impacts that threaten food supplies, is cutting emissions to net zero, so as to stop adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. The Paris Agreement seeks to limit temperature rises to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. At around 1.3°C of warming, we already see the threats and growing danger; this only worsens with each fraction of a degree of temperature rise.

The global clean energy transition – the principal means of achieving net zero – has been driven by policy decisions flowing from nations’ commitment to Paris, with investment in renewables internationally now running at twice the level of investments in fossil fuels each year.

Until we get to net zero emissions, to stop extreme weather getting worse, we will continue to see increasing volatility in our food system. This is because the stable climate that our crops and livestock have been developed to thrive in is rapidly changing.

Adapting to worsening impacts

We also need to adapt to the climate impacts we’re seeing now, at the current rate of warming, especially as we remain on track, as global policy commitments currently stand, for temperature rises between 2.6° and 3.1°C. Farmers, everywhere, are among some of the most vulnerable to climate extremes.

Climate finance from wealthy nations to producer countries with low climate readiness is a key part of the solution, supporting farmers to adapt to climate impacts and secure their crops and livelihoods – both for consumption at home, and for export.

Nations that met at COP29 in Baku agreed that climate finance will rise. Although nowhere near the £1.3 trillion a year by 2035 that experts say is needed globally, world leaders agreed the level should treble from the current $100 billion a year to at least $300 billion.

Despite this, 2025 has seen many nations retreat from commitments on overseas development assistance. In the UK, the government has significantly cut the Official Development Assistance (ODA) budget to partially offset an increase in defence spending. The ODA budget funds our climate finance commitments, which includes support to farmers all around the world who grow staples like rice, bananas, coffee and a whole range of fresh fruit and vegetables that we import.

The UK is already coming to the end of its third round of climate finance commitment, which will total £11.6 billion over five years, from 2021/22 to 2025/26. Some of that goes in bilateral support, directly to nations that need our support. And some of it goes via large, global multi-lateral funds, such as the Green Climate Fund. ECIU analysis in 2024 showed that UK climate finance, via the six largest multi-lateral funds, had contributed to at least 348 projects supporting overseas farmers hit by climate change in 111 countries, 84 of which (76%) grow food sold on UK supermarket shelves.

Food security is an element of national security. Withdrawal from overseas aid and climate finance would leave some of the world’s most vulnerable farmers exposed to climate change, with the potential to undermine global food production.

An example of UK climate finance supporting Brazilian farmers

The Rural Sustentável programme runs from 2016-2026. Its aim is to reduce deforestation by improving agriculture and land use practices among rural producers in Brazil. It directly supports the implementation of the Low-Carbon Agriculture Plan by the Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture.

Activities supported include forest restoration on degraded pasturelands and the adoption of sustainable low-carbon agriculture, which can improve agricultural production whilst protecting native vegetation. This is leading to a more sustainable system of agricultural production – safeguarding food supplies – whilst also securing sustainable livelihoods for rural communities across the Amazon, Cerrado and Caatinga areas of Brazil.

The Caatinga biome within this programme is located in Northeast Brazil, where agriculture plays a key economic role; it is home to approximately 32% of Brazilian farms. Traditional agricultural practices, such as the use of slash and burn and overgrazing, are common, causing land degradation and increasing desertification. The project has provided technical assistance to small and medium-size local farmers in the adoption of climate-smart technologies in addition to training farmers and rural organizations to support adoption of these technologies. Support to value chains and market access has strengthened the capacities of small farmer organisations through the financing of collective benefits, such as water storage, seedling nurseries, smallscale storage facilities, and tools for compost production.

Photo: Icaro Cooke Vieira/CIFOR - via Flickr