DeafTurbineGate - when headlines go bad

Inside the nacelle of journalistic cock-up and confirmation bias

By Richard Black

Share

Last updated:

By Richard Black, ECIU Director

For anyone outside the journalism trade, it might be mystifying how articles that have little basis in reality appear in the national press.

But it happens. It happened yesterday, when four papers – the Telegraph, Mail, Times and Express – all published articles on a piece of research that they claimed showed wind turbines could make people deaf.

Let’s hear from Markus Drexl, the University of Munich scientist who led the research team:

‘It's definitely not what we're saying in the paper. You cannot make this claim.’

‘It is certainly misleading and an over-interpretation of our results to state that living close to wind farms may cause hearing impairment or deafness. Our research did not include any work at wind farms.’

So how do stories like this make it through the checks and balances of journalism? Conspiracy, cock-up, confirmation bias or copycatting?

Missing link

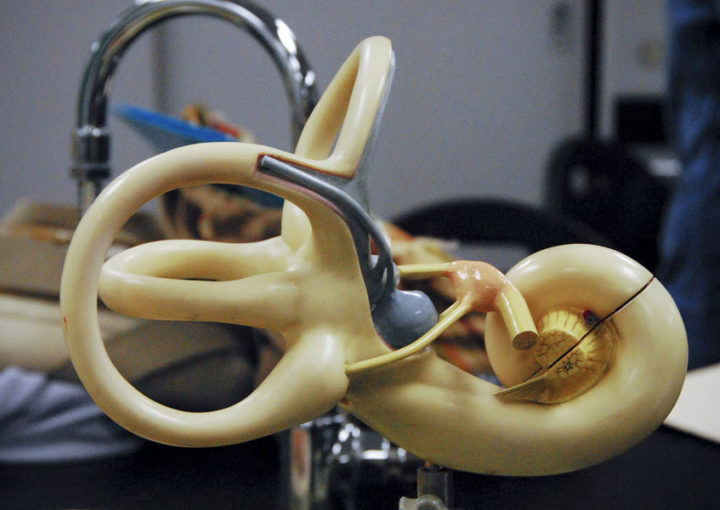

The research in question, from the University of Munich, exposed people, in a laboratory setting, to infrasound. This is very low frequency sound, so low that we don’t experience it really as sound, but which nevertheless does affect the ear.

But wind turbines were not used in the research; and the scientific paper that related the research findings didn’t mention wind turbines at all. Not once.

However, a note was circulated to journalists about the research, which did mention them. The intention was clearly to make the research appear real-world-relevant by including examples of things that generate infrasound:

‘Anthropogenic sources of low-frequency noise have spread exponentially within recent years through the advent of eg wind turbines, block-type thermal power stations, ventilation, and air-conditioning systems... while even loud low-frequency sounds are not perceived as obtrusive, our findings show that such sounds affect the exquisite mechanics of our inner ears in a significant manner.’

You’ll note that this does not link wind turbines to the university’s research, but to something that’s happening in society. But – and here’s the ‘cock-up’ part, at least from the university’s point of view – it gave enough ammunition to trigger a journalistic reflex.

This is where confirmation bias kicks in – the tendency to give weight to, or find comfort in, or re-tweet, ‘findings’ that support your own prejudices.

I doubt that anyone is immune from confirmation bias. I certainly found it prevalent in newsrooms – perhaps because news journalists process a vast amount of information each day, on a huge variety of topics, without having too much time to examine them.

So there is a tendency to believe that X or Y is true because you read it somewhere once – or because everyone else seems to be saying so.

One such belief is that renewables are unpopular – ‘everyone hates wind turbines’. It’s not true – government surveys for example show that renewables enjoy about 80% support, and they’re not alone.

Even so, it’s a meme that is alive and well in a number of editorial offices.

So, a reporter sees an opportunity to write a story that is likely to get published because it chimes with the collective confirmation bias on the editorial desk. Or, an editor sees the story and asks the reporter to write it.

Thus is a deal struck between story 'seller' and story 'buyer', posited on the expectation that it will conclude what both parties need it to conclude – in this case, that living near a wind turbine can make you deaf.

The next link in the chain is the scientist, phoned up for a quote. Describing the phenomena he had found during his non-wind-turbine-based research, Dr Drexl told the Telegraph:

‘This could be a first indication that damage might be done to the inner ear.

‘We don’t know what happens if you are exposed for longer periods of time, [for example] if you live next to a wind turbine and listen to these sounds for months or years.’

The quotes don’t actually say that the research shows wind turbines damage hearing – but neither do they say the opposite. The most relevant technical question – ‘are the sound levels that you used in your experiment similar to sound levels experienced by living near a wind farm?’ – does not appear to have been asked. If it had been, it would have weakened the article, because the sound levels are very different between experiment and actual wind farm.

And so the story is cleared for take-off.

Chasing lines, losing trust

The final link in the chain of dissemination is the ‘me-too’ reaction of newsdesks. If an editor sees that one organisation is running a story that (s)he likes – which often means that they share the same confirmation bias – the tendency is to recycle it. With speed at a premium these days, the chances that they will stop to check the facts are vanishingly small. So, facts and nuances get further mangled.

And so the Telegraph’s line that ‘Living close to wind farms may lead to severe hearing damage or even deafness’, and the Mail’s ‘Wind farms could cause people living nearby to go deaf, a new study claims’ – the latter of which is already untrue, as the study did not claim that at all – transmogrify into the Express’s ‘Turbine buzz “is deafening”’.

Once invented, such memes circulate, strewn like particulates from the chimney of a coal-fired power station.

Whether anyone outside the circle of confirmation bias believes them is another matter. Trust in newspapers to report climate issues accurately is shockingly low. Print journalists are generally trusted less on climate than politicians of all parties, and definitely less than the European Union. Stories such as this could well be part of the reason - although, let's be clear, I'm speculating.

That papers continue to print anti-renewable stories by the drove is also intriguing given that the public supports the technology. Would it seem like good business to print anti-football stories in Liverpool, or anti-oil stories in Aberdeen?

For the journalist, the really good stories are the ones that challenge what we know – or what we think we know – rather than confirming it. They may be more difficult to get past the editor, but the satisfaction at the end of the process is far greater. Woodward and Bernstein didn’t win a Pulitzer for reporting an everyday break-in.

Share