How much hope from 'Hopenhagen'?

Five years after the seminal UN climate summit, what's changed?

By Richard Black

Share

Last updated:

Most visitors’ memories of Copenhagen centre on the rituals of the Amalienborg Palace, a ride on the Tivoli Gardens’ rollercoaster and a quick selfie with Hans Christian Anderson’s Little Mermaid.

But for about 40,000 of us, the word ‘Copenhagen’ will always conjure up a very different memory - a fortnight that commenced exactly five yerars ago, spent in the boxy hangar of the Bella Centre, watching governments’ plans to agree a global deal on climate change unravel thread by thread.

So with the next big attempt to agree a global climate deal scheduled for a year hence in Paris, what lessons can we usefully draw from Copenhagen?

And what’s changed since 2009 that could meaningfully affect prospects for success or failure next year?

Three big trends

The climate world has changed in three meaningful ways since 2009.

Firstly, low-carbon technologies have become far more attractive, both economically and in terms of understanding how they can best be used.

The most dramatic change has been in solar power. The real price fall depends a bit on where you live in the world; a conservative figure is that the price has fallen to less than half of its 2009 level, while others analyses speak of an 80% fall.

Wind power prices have also fallen.

Both look like really mature technologies – manufacturing of standard models shifting to low-cost Asia, while western companies innovate with higher-efficiency solar cells and bigger, sometimes floating wind turbines.

Just as importantly, engineers are gaining an ever better understanding of how to build a renewables-based energy system.

A particularly good example is a report last week from the Fraunhofer Institute showing that the German Energiewende model is entirely and economically feasible with the right flexibility mechanisms.

Technology does not yet have all the answers. Nuclear is struggling in some countries, carbon capture and storage still languishing, electricity storage and electric cars exciting but still raw.

But there is no question that progress since Copenhagen has been startling. Countries such as China and India are already investing heavily in this future, and the end of coal use is now in sight – a huge boost for prospects of a climate agreement.

The second big change since Copenhagen is scientific.

It’s something of a cliché to say that ‘the science on climate change has become clearer’. It’s largely true; but the point is made more strongly when looking at certain specific areas.

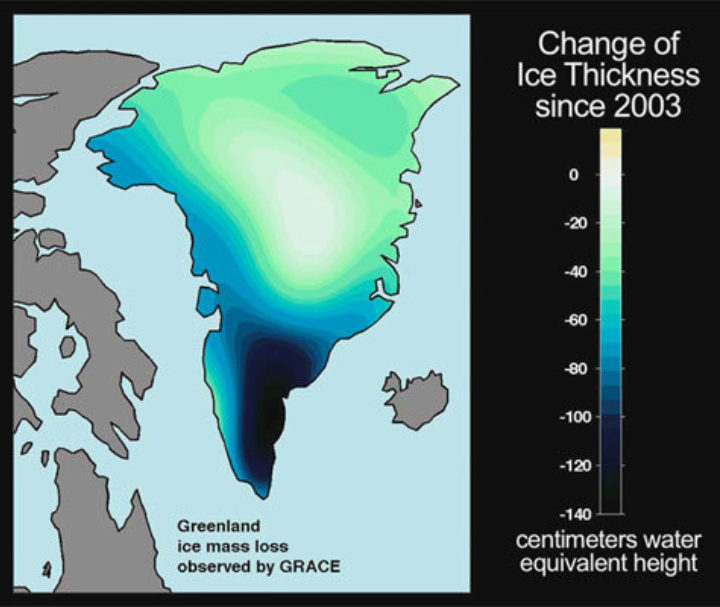

Instrumentation is answering questions that remained murky before. The network of Argo floats is yielding far more data about the oceans than existed before. The Grace satellite mission has mapped changes in the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets in astonishing, unanswerable fashion.

On the analytical side, the science of attribution is developing fast, making it possible to assess how much the risks of extreme events rise with climate change.

As a result, governments can begin to calculate the costs and benefits to their own economies of decarbonising versus not decarbonising.

Another major development is the calculation of carbon budgets, illustrating how fossil fuel burning has to be constrained if governments are serious about the 2 Celsius target.

The third major development is political.

Copenhagen basically terminated the idea that government delegations would look at the messages from climate science and decide within the UN talks how to share out the carbon cuts indicated.

This model had in reality been dying for years, but it finally and visibly perished in the Bella Centre.

Painfully, slowly, confidence has been patched up after that shattering experience.

The US and China, which together account for almost half of global emissions, were then engaged in a stand-off. Now, for the moment at least, they stand together. Europe is just doing enough to stay in the game, and the highly vulnerable developing states have started to take a stronger leadership role.

As a result, much of the groundwork for a deal in Paris has already been done, both inside and outside the UN climate convention, in a way that was absolutely untrue before Copenhagen.

And as a result of these trends, investors and businesses are increasingly looking at their portfolios and asking whether investing in a fossil fuel future is sensible – which in turn reduces pressure on governments to keep stoking the boilers of energy-as-usual.

‘(Still No-)Hopenhagen’?

These developments have mainly come about despite Copenhagen. But a case can be made that the summit's startling denouement changes did accelerate the transition to a more pragmatic politics.

It confirmed that a new model was needed where countries present their own plans and then haggle. It clarified that a ‘G2-plus’ process, as the recent China/US agreement can be termed, was necessary (although not sufficient).

Both have happened. The voices of the poorest countries most vulnerable to climate impacts have been somewhat marginalised in this new world order; but still, it is more orderly than the old.

And the acceptance of this new order within the UN climate convention means that the UN convention has stayed politically relevant; after Copenhagen, it could well have ended up as a sideshow to which the great powers paid little heed.

For the 2009 summit, the PR boys and girls decided to re-brand the city ‘Hopenhagen’. On one of my final despatches for the BBC from the snow-bound capital, I stuck the word ‘No’ in front of that.

A mere five years on, thanks to solar power, satellites and smarter politics, I don’t think that is what we’re looking at anymore.

Share